Andy Warhol and the Art of Judging Art

Julia Longoria: Hello, everyone. We made it. It's the final episode of this season of More Perfect.

Thank you for listening to our show. Before we get started, I want to take a minute to remind you that More Perfect is a public media podcast, which is an amazing thing. It means we rely on support from listeners to make our show possible.

It takes a lot of time and resources to make each episode of this show. We've got multiple producers, editors, fact checkers, legal advisors, sound designers. This is what you make possible when you donate to support our show. Listeners who donated before you funded this past season, and your donation is gonna help fund our upcoming season.

So please, right now, go to MorePerfectPodcast.org/donate or text “Perfect” to 70101. It's only gonna take you a few minutes. We promise. And now onto the show.

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Um…

Julia Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria. This is More Perfect.

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Warhol: Um… uh…uh… no.

Julia Longoria: And this -

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Uh…yes, yeah…no.

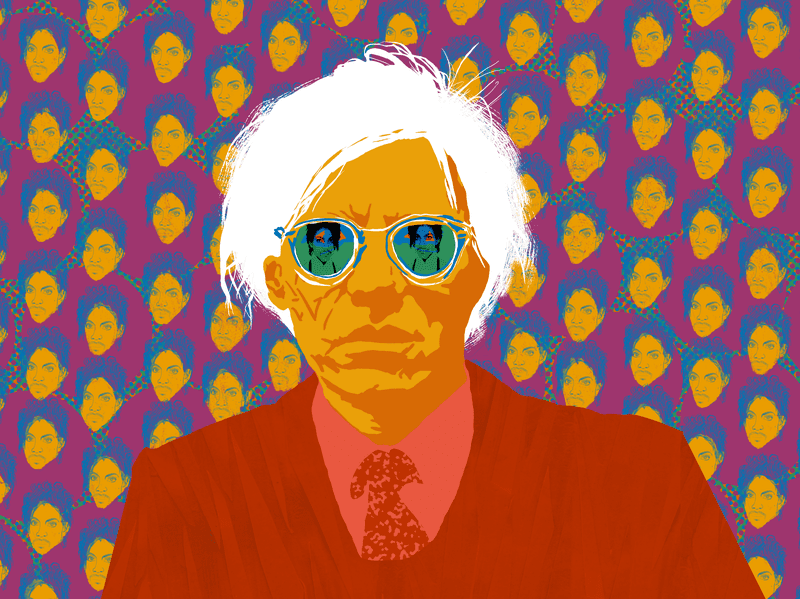

Julia Longoria: is pop art icon Andy Warhol.

[Archive, Male Interviewer]: In other words, you have no vision of the past, the artistic trend, no vision of the future trend, you're just doing whatever you feel like?

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Well, yeah.

[music]

[Archive, John Roberts]: We will hear argument first this morning in case number 21 8 69, Andy Warhol Foundation versus Goldsmith.

Julia Longoria: The ghost of Andy Warhol visited the Supreme Court this term. While most of the other cases were filled with heated conversations in legalese, here…

[Archive, Samuel Alito]: You make it sound simple but maybe it's not so simple, at least in some cases...

Julia Longoria: …the justices found themselves debating the meaning of form…

[Archive, Samuel Alito]: What is the meaning or the message of, of a work of art?

Julia Longoria: …and color…

[Archive, John Roberts]: But I'm sure there's an art critics who will tell you there's a great difference between blue and yellow…

Julia Longoria: Because at the center of the case are two pieces of art.

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Well, I don’t know. I never call my stuff art. See? It's just work.

Julia Longoria: Okay, at the center of the case are two pieces of work.

Female Line Speaker: One looks like a photograph and one looks like a painting. Yeah, but it looks like someone painted that from the photograph.

Julia Longoria: The photograph is a black and white portrait of a face that’s familiar to a lot of people

[music: “Kiss” by Prince]

Julia Longoria: The musician and cultural icon… Prince.

Female Line Speaker: And I'm a fan, so I recognize the image right away.

[music: “Kiss” by Prince: Don’t have to be beautiful…]

Julia Longoria: It was taken by celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. The other is the same image of Prince’s face, but the whole thing is colored in orange. It’s got an unmistakable Warhol look.

[music]

Going into the case, a question at the center seemed to be: Was Warhol’s portrait transformative?

Female Line Speaker: Transformative? Define that.

Julia Longoria: Did it transform Goldsmith's original photo into something so new and different that it was okay for the Warhol Foundation not to have paid her or gotten her permission to use the photo first?

Female Line Speaker: The image on the left is just a simple photograph. A nice photograph. The image on the right turns it into art, I don't know.

Female Line Speaker: No.

Female Line Speaker: You can clearly still see the original image and it's pretty clear.

Female Line Speaker: I don't know!

Jerry Saltz: They're almost not from the same planet.

Julia Longoria: That last voice is art critic Jerry Saltz, from New York Magazine.

Jerry Saltz: I would argue the photograph was just a drawing. Just a sketch. Just an inspiration. I believe that these works of art that Warhol created, totally 100% transform the original product.

Julia Longoria: To Jerry, there’s no question. The Warhol is transformative.

Julia Longoria: I actually happen to disagree with you, I think? But like…

Jerry Saltz: In my own opinion, I'm a hundred percent right. You, in my opinion, are very, very conservative [laughs] and I am radical! [laughs]

Julia Longoria: I quickly learned this case is kind of fun to talk about because it shakes up traditional liberal and conservative divides. If you’re starting to talk to people about it - it’s really hard to predict who they’re gonna side with.

Jerry Saltz: Let's just say I'm the conservative one to make this easy, and you're ultra radical.

Julia Longoria: It is fun to be a radical, isn't it?

Jerry Saltz: Yeah. You're the radical. I'm the conservative. Okay?

Julia Longoria: [laughs] Okay. Cool.

Jerry Saltz: I hate the idea that Justice Alito and those other dweebs are discussing this because to me, it's not a legal issue, it's a taste issue.

Julia Longoria: The legal question was whether the Andy Warhol Foundation violated the photographer’s copyright. And in the oral argument, you can hear the justices trying not to sound like art critics.

[Archive, Samuel Alito]: How is a, a Court to determine the message or meaning of works of art, like a photograph or a painting? How does the Court go about doing this?

[OYEZ OYEZ]

Julia Longoria: So this week on More Perfect, we're going to find out how they go about doing this - interpreting art.

We have the artist Andy Warhol… who claims he’s not making art? The photographer… who claims Andy Warhol’s a copycat. And Supreme Court justices who insist they are not art critics.

And watching the judges tiptoe into the squishy world of art, where right is left and left is right, allows us… honestly? a –break– from all the depressing partisan politics. And possibly? a more clear-eyed look at how the U.S. Supreme Court actually makes decisions.

[OYEZ OYEZ]

Julia Longoria: I'm Julia Longoria. This is More Perfect.

The Docket this past term was filled with explosive and fraught issues: affirmative action, voting rights, anti-discrimination laws. And then, there was a case about Andy Warhol. On paper, it looked like the fun case this term…

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: Warhol's transformative meaning puts points on the board under factor one of the four factor balancing test.

Julia Longoria: …in practice, maybe less fun?

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: If you look at Judge Leval's article on page 1111,

Julia Longoria: Producer Alyssa Edes waded into the weeds…

Alyssa Edes: Test 1, 2, 3. Test 1, 2, 3.

Julia Longoria: to rescue the fun.

Pierre Leval: 1, 2, 3, 4. This seems to be recording.

Alyssa Edes: You can trace the origin story of the Andy Warhol case back to this man.

Pierre Leval: My name is Pierre Leval. I'm a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Alyssa Edes: When Judge Leval was in law school, at a certain school in Boston…

Pierre Leval: At the Harvard Law School, everybody told me that copyright is the most fun course in the school. I should definitely take it in my third year. And I thought to myself, that would be immature of me. I should choose a course that will be useful to me in the future. And then it turned out that not too far into the future, I became a federal judge with responsibility to decide copyright law. And I didn't know anything about copyright law.

Alyssa Edes: Judge Leval shoulda taken the “fun class.”

Julia Longoria: So wait, why is copyright fun for, for law students?

Alyssa Edes: Right so, copyright is this area of the law where there’s a lot of creativity kinda? Because the Constitution doesn’t say a whole lot about it.

Julia Longoria: I just wanna like, for a second, just bear with me. I wanna pull out metaphorically my pocket Constitution, but really just gonna look it up. Article 1. Copyright. So. Here it is. Congress can 'promote the progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited times to authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective writings and discoveries’ Sounds like a blast. [laughs]

Alyssa Edes: Yeah, so it’s a lot of words. Basically, the Constitution wants to advance arts and sciences right? – for the whole of society. And the way that it gets there is by saying, we’re gonna protect creators from copycats. But that protection is also limited. And over the next 200 years, judges decide it’s *ok* to copy sometimes – there are times when stuff might be fair to use.

Pierre Leval: Fair use is entirely created by judges. I mean, eventually it was adopted into the law.

Alyssa Edes: But in the 80s, when Leval is getting his first copyright cases, judges had been largely improvising their answer to what is fair to use on an opinion by opinion basis.

Pierre Leval: None of those judicial opinions ever undertook to tell you, how do you discern

Alyssa Edes: Mm-hmm

Pierre Leval: whether a use is fair use or not?

Julia Longoria: Yeah. How are you supposed to tell? Seems like…

Alyssa Edes: Yeah. Um… I dunno! [laughs]

Pierre Leval: So, judges were essentially deciding from the gut and that's, that's not a good thing for the law.

Alyssa Edes: Leval says usually judges have a way of avoiding making decisions from the gut.

Pierre Leval: When a case comes before a judge, the judge must decide for one side or the other.

Alyssa Edes: Mm-hmm.

Pierre Leval: And in order to do that in a manner that tells the world this is being done according to law, rather than just according to how I feel at this particular moment, the judge has got to explain the decision in terms of generally applicable standards.

Alyssa Edes: Generally applicable standards: In other words, the judges want to be able to say, we're not making this stuff up! We got rules!

Pierre Leval: This is an inescapable part of the judge's job!

Alyssa Edes: He says standards are the building blocks of judging.

Pierre Leval: I mean, it's like an engineer thinking about what materials are going to be adequate to hold up a bridge when trains and cars and trucks and so on are crossing the bridge.

Alyssa Edes: A legal standard sturdy enough to apply to all different kinds of situations – movies, books, music, podcasts that use stuff from other places. Leval thinks that like engineers, judges can “stress test” a standard to make it objective.

Pierre Leval: If you don't do that, if you just say well, this seems right to me, you have not fulfilled your function and, and, uh, it is an increased likelihood that the bridge will collapse under bad conditions.

Alyssa Edes: And in cases involving fair use, Leval says there was no general standard. So, he decided to build the bridge himself.

Pierre Leval: I undertook to at least make steps in the direction of outlining what standards should be for determining whether something is or isn't a fair use.

Alyssa Edes: He came up with an idea for a new standard:

Pierre Leval: Transformative use.

Alyssa Edes: When might it be ok to copy someone else’s work? When the copy transforms the original. In 1990, Pierre Leval writes this hugely influential law review article essentially saying, to be transformative, a piece of art…

Pierre Leval: It should seek to communicate something very different from what the original author was seeking to communicate.

Alyssa Edes: And that the work should add “new information, new aesthetics, new insights, and understandings.” Which, honestly [chuckles]… I don’t know. Is still kind of vague?

Pierre Leval: So the thing that's trying to be described is complex and it's, uh, I don't claim that the word transformative is all you need to know to answer all the questions. It's a, it's a stab in the direction of explaining what it is about a certain type of copying or using of another's work that, uh, will help you get in the door of fair use, of permitted copying as opposed to prohibited, unauthorized copying.

Alyssa Edes: This transformative test takes the copyright world by storm. This little idea in a law review article makes it big and finds its way to the Supreme Court.…through a case about music.

[music: APM library track]

Alyssa Edes: Okay, so picture this, it's the 1980s. The parties are wild.

David Hobbs: The girls was doing what they call twerking now. They was just calling it shake dancing back then.

Alyssa Edes: And there's this lil hip-hop group making a big name for itself, and that group is 2 Live Crew.

David Hobbs: My name is David Hobbs, also known as DJ Mr. Mixx. If there's no me, there's no 2 Live Crew, that's my intro.

Alyssa Edes: Mr. Mixx grew up just outside L.A. He was always musical.

David Hobbs: Um, yeah. When I was a kid, there was a guy that played the saxophone called Junior Walker – he was really dynamic and I would see him on TV.

[saxophone music]

Alyssa Edes: He learned to play the saxophone when he was a kid, sort of mimicking records by ear.

David Hobbs: I would take records from my Pops’ collection and bring them back to my room and try to figure out the notes. We'll play along with, you know, the melodies that I heard on the records.

Alyssa Edes: He gets to take some music classes in school, but instead of turning it into a career right away, he joins the Air Force. And it's in the Air Force that he gets introduced to hip-hop.

[music: Rock Steady Crew: Hey You]

Alyssa Edes: He's stationed in England…

[music: Rock Steady Crew: Hey You]

Alyssa Edes: and…

[music: Rock Steady Crew: Hey You]

David Hobbs: The Break dancing group Rock Steady Crew came to, uh, England to do a, um, exhibition and I went to one of them and, um, they had a DJ with them.

Alyssa Edes: And this is the first time Mr. Mixx sees somebody DJ. And he’s just like, hooked.

David Hobbs: When I actually seen him do it, and I seen one hand was on the record going back and forth in a, you know, in a scratching motion in the same way, like you would scratch your arm.

Alyssa Edes: Yep.

David Hobbs: Okay, so now I get to understanding why they call it scratching.

Alyssa Edes: So, he leaves England, the Air Force stations him back, uh, in California.

David Hobbs: I went and got me two makeshift turntables and a makeshift mixer and started practicing in the barracks, honing my skills.

[DJ scratching]

Alyssa Edes: Just like when he was a kid with the saxophone listening to his dad's records, imitating the stuff that he was hearing, you know, he's now taking something and making it into his own thing.

David Hobbs: I'll put it to you this way, the way that hip-hop originated, you took a record that people already recognized

[music: The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel - good times sample]

David Hobbs: And you do it your own way or you take elements from it to make it a little more unique based on what it is that you did.

Alyssa Edes: Fast forward, Mr. Mixx forms 2 Live Crew with some friends, and they’re blowing up in Miami. And their music and their shows are super raunchy.

[music: Me So Horny]

Alyssa Edes: They had this album called “As Nasty As They Wanna Be” which was banned by a federal judge for being obscene. But their thing was, like, being outrageous – like, how far could you push it? So in this spirit of humor, they’re taking things they think will be recognizable…

[music: Roy Orbison - Oh, Pretty Woman]

Alyssa Edes: and making fun of them. And, um, in 1989, they land on the Roy Orbison song…

[pretty woman, walking down the street…]

Alyssa Edes: As something that would be fun to rip and mix.

[music: 2 Live Crew - Pretty Woman: Two-timing woman, girl, you know you ain’t right. Two-timing woman, you was out with my boy last night.. Two-timing woman…]

David Hobbs: You know, childish humor, that's what we were doing. But it was childish humor in a way where it could be a lot of money was made.

Alyssa Edes: Mm-hmm.

David Hobbs: But I guess their beef was that we didn't get permission from them to do it.

[music: 2 Live Crew - Pretty Woman: ohhhh, oh! Pretty woman.]

Alyssa Edes: And uh, to no one's surprise, they get sued. And they end up in the Supreme Court.

[Archive, William Rhenquist]: We'll hear argument first this morning. Number 92, 12 92…

Alyssa Edes: And the question is, can 2 Live Crew’s version of Pretty Woman be considered fair use as a parody?

[Archive, Bruce Rogow]: That is the purpose of parody, to borrow from the original and then to imitate and ridicule the original, which is what happened in this case.

David Hobbs: The thought process is taking the groove of the record and saying some funny stuff based off of what the original actually is. So we were making a parody, but we didn't really think about it in that way, like that's what we were really doing.

[Archive, William Rhenquist]: Uh, we now reverse and remand. A parody like other comment and criticism may claim to be fair use. And the court of appeals…

Alyssa Edes: So Justice David Souter writes the opinion and all nine justices sign onto it. He says, this parody is a clear example of fair use. And he declares a new standard: to make these kinds of decisions, judges are supposed to gauge whether and to what extent a new work is transformative. And he puts a citation after that: Leval.

Pierre Leval: Well, I was pretty thrilled.

Alyssa Edes: Why?

Pierre Leval: Well, because they, because they took my article and used it kind of as a blueprint!

Alyssa Edes: This was a victory for 2 Live Crew and for Pierre Leval, who became a giant in the “fun” area of the law, much to his surprise.

Julia Longoria: And weirdly, it seems to me like, Justice Souter is taking Leval, and sort of remixing him in a way?

Alyssa Edes: Totally, totally. That is part of what judges do. They're adding on to each other's work. They're seeing what's come before, they're taking things other people have said and putting it in new contexts, writing new stuff. And now similar cases that come after it are decided using Leval's transformative use standard. It becomes the beating heart of fair use law.

Julia Longoria: Hmm.

Alyssa Edes: Then, Warhol comes along.

[Archive, Male Interviewer]: Well then, what's the difference between, uh, a photograph and a painting? That's a big difference.

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: [inaudible]

[Archive, Male Interviewer]: There is no difference?

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Yeah. No, I like photographs better.

Alyssa Edes: … arguably the most famous American artist of the last hundred years, whose signature style is based on appropriating and transforming other peoples’ images. And the question now is, almost 30 years after the Supreme Court handed a victory to a Pretty Woman parody, what will this particular Court make of Warhol’s work?

Julia Longoria: That's after the break.

[DJ scratching]

Julia Longoria: From WNYC Studios, this is More Perfect. I'm Julia Longoria.

Judges have always had a hard time figuring out how to rule on cases in the squishy world of art. That area of the law is dominated by vague questions like, is it “fair?” So when one judge, Pierre Leval, added the arguably more specific question “Is it transformative?” - judges were into it. The Supreme Court used it to decide a case about a hip-hop parody, and they made Leval’s transformative standard go platinum.

Which brings us to the Andy Warhol case.

Here’s Producer Alyssa Edes.

Alyssa Edes: Yeah, so: it’s the very powerful Warhol Foundation, versus Lynn Goldsmith

[Archive, Lynn Goldsmith]: In 1981, I made a studio portrait of Prince.

Alyssa Edes: The photo is black and white. It’s Prince from the waist up, white shirt, suspenders. He looks sort of vulnerable, with this really direct stare into the camera. And at the time, it’s still early on in Prince’s career, so he's this up-and-coming artist. Then a few years later…

[music: Prince - Purple Rain]

Alyssa Edes: Prince is an icon at the top of the charts. Vanity Fair wants to feature him in the magazine, and they hire Andy Warhol, to do a portrait of Prince.

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Now I do some, you know, uh, portraits of people…

Alyssa Edes: And Warhol takes Goldsmith’s vulnerable, black and white photograph and he makes Prince’s gaze look stronger. Almost unshakable. And he makes Prince purple, he disembodies his head, changes a few things here and there, and Vanity Fair runs it. They credit Goldsmith for the use of the photo, and they pay her $400.

Julia Longoria: So far, everything's fine, right? Everyone's been paid, everything's fine. [chuckles]

Alyssa Edes: Yeah, everything's fine. Um, everything’s fine for quite a while. Until 2016.

[Archive, Male Newscaster]: There is breaking news from Minnesota, the singer, songwriter, and musician known as Prince has died.

Alyssa Edes: There's all of these outpouring of remembrances…

[Archive, Male Newscaster]: A great musician, a great producer, great songwriter.

[Archive, Male Newscaster]: Possibly the most talented, charismatic, entertaining, influential, and

Alyssa Edes: Lynn Goldsmith is seeing all this coverage just like anybody else. And she comes across the cover of a magazine about Prince…

[Archive, Lynn Goldsmith]: And I look at it and I think that's really familiar looking. And I, uh, I looked in my files cuz I, I never forget someone's eyes.

Alyssa Edes: It’s another Warhol silkscreen. This one is orange, but she can tell it’s still her photograph of Prince. So she sees this and starts to say, Uh, what, what is that? [chuckles] I never saw that before! By this point Andy Warhol had passed away.

[Archive, Lynn Goldsmith]: So I called up The Warhol Foundation and I said, you know, I've discovered this. Here's the original invoice, here's the original picture, and I'd like to talk to you about it.

Alyssa Edes: One thing leads to another…

[Archive, John Roberts]: We will hear argument first this morning in case Number 21 8 69, Andy Warhol Foundation

Alyssa Edes: And it ends up at the Supreme Court.

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court.

Alyssa Edes: The Warhol lawyer goes first…

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: The stakes for artistic expression in this case are high. A ruling for Goldsmith would strip protection not just from this Prince series, but from countless works of modern and contemporary art.

Alyssa Edes: He says the Court should be doing the same thing they did in the 2 Live Crew case.

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: If you look at Judge Leval's article on page 1111

Alyssa Edes: And he says: Warhol, transformation? He passed that test! He transformed Prince into an icon.

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: A picture of Prince that shows him as the exemplar of sort of the dehumanizing effects of celebrity culture in America.

Alyssa Edes: But the justices push back on this whole idea…

[Archive, John Roberts]: Uh, is that enough of a transformation?

Alyssa Edes: Under Leval’s test, how can judges tell if the meaning or message has been transformed enough? How can a Court even tell what the meaning or message of a piece of art is?

[Archive, Samuel Alito]: Uh, should it receive testimony by the photographer and the artist? Do you call art critics as experts? How does the Court go about doing this?

Alyssa Edes: Justice Alito suggests the Court can’t really do the work of art critics. And then, you hear Chief Justice Roberts start to do what the Supreme Court does in almost every case:

[Archive, John Roberts]: Let's suppose that, you put a little smile on his face and say this is a new message. The message is, Prince can be happy. Prince should be happy.

Alyssa Edes: He begins to throw out hypotheticals. And they use these hypotheticals to “stress-test” the transformative standard. (Leval’s bridge.)

Pierre Leval: Supposing that we subject this bridge to predictable, serious stresses. Stresses of tornado force winds, trains loaded with heavy cargo, collision happening on the bridge, and uh, use our mathematical tests and whatever else there are to see whether, is it gonna hold up under those circumstances?

Alyssa Edes: If you didn’t know this is what the justices do…

[Archive, John Roberts]: Let's say somebody, uh, uses a different color.

Alyssa Edes: It might sound like they’re just going off the rails. Here’s Clarence Thomas.

[Archive, Clarence Thomas]: Let's say that, um, I'm both a Prince fan, which I was in the 80s. And, um,

[Archive, Elena Kagan]: No longer?

[laughter]

[Archive, Clarence Thomas]: Well [laughter] So, uh, only on Thursday nights.

[Archive, Elena Kagan]: Mm-hmm. [laughter]

[Archive, Clarence Thomas]: But, uh, let's say that I'm also a Syracuse fan.

Alyssa Edes: And he’s like, what if I make a giant Orange-Prince-head poster for a Syracuse game?

Thomas: And I'm waving it during the game with a big Prince face on it. Go orange.

Alyssa Edes: Go orange. Is that transformative?

[Archive, Amy Coney Barrett]: If a work is derivative…

Alyssa Edes: Then, Amy Coney Barrett brings up Lord of the Rings.

[Archive, Amy Coney Barrett]: Lord of the Rings, you know, book to movie.

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: Uh, I don't think that Lord of the Rings has a fundamentally different meaning or message, but I would have to prob…

[Archive, Amy Coney Barrett]: The movie?!

Alyssa Edes: Seems like she’s a fan.

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: but I would probably have to learn more and read the books and see the movies to give you a definitive judgment on that. [laughs] And I recognize that reasonable people…

Alyssa Edes: It goes on like that for a while. Until...

[Archive, John Roberts]: Thank you, counsel.

[Archive, Roman Martinez]: Thank you.

[Archive, John Roberts]: Ms. Blatt?

[Archive, Lisa Blatt]: Thank you Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court.

Alyssa Edes: Goldsmith’s lawyer gets up to speak.

[Archive, Lisa Blatt]: If petitioner's test prevails, copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats.

Alyssa Edes: And she argues the whole “new meaning and message” part of the transformative test is kinda bullshit.

[Archive, Lisa Blatt]: Anyone could turn Darth Vader into a hero or spin off All In The Family into The Jeffersons without paying the creators a dime.

Alyssa Edes: She’s like, if anyone can take something and make a tiny little change and call it theirs, then basically there’s no copyright protection for anything.

[Archive, Lisa Blatt]: Your test lies madness in the way of almost every photograph to a silkscreen or a lithograph, or any editing. I guarantee the airbrushed pictures of me look better than the real pictures of me, and they have a very different meaning and message to me! [laughs]

Alyssa Edes: John Roberts is like, isn’t Warhol doing something bigger?

[Archive, John Roberts]: It's not just that Warhol has a different style. It's a different purpose. One is the commentary on modern society. The other is to show what Prince looks like.

Alyssa Edes: But Goldsmith’s lawyer is like, you’re missing the point!

[Archive, Lisa Blatt]: So, where I think all this goes wrong is you're just focusing on meaning and message independent of the underlying use.

Alyssa Edes: In other words, this isn’t about aesthetics, this is about money. And the market.

[Archive, Lisa Blatt]: Even Warhol followed the rules. When he did not take a picture himself. He paid the photographer. His foundation just failed to do so here.

[music]

[Archive, Male Interviewer]: If you could just summarize briefly, because this was a big case, a David versus Goliath case. Yeah. This is a huge, huge copyright case that will have massive implications for artistic creators.

Alyssa Edes: After the decision came out, Lynn Goldsmith went on the radio to talk about it.

[Archive, Lynn Goldsmith]: I, the reason I risked everything I have was I wanted to make sure, as best I could, that the copyright law would be one to protect all artists.

Alyssa Edes: The Court rules 7-2 in Goldsmith’s favor. But what’s funny about it is they did it in kind of a very Warhol way?

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Well, I don’t know. I never call my stuff art. See? It’s just work.

Alyssa Edes: Warhol’s whole artistic project is arguably a commentary on American consumerism, the way everything is a commodity: Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe, Prince, even Warhol’s own art.

And the irony is, the justices kind of agree with him here!

They treat his work like a commodity. And reason that the Goldsmith photograph and the Warhol silkscreen were both licensed to magazines (to go with articles about Prince).

So, they’re serving the same PURPOSE in the same market. And that means, no transformation. The Warhol Foundation was wrong.

Julia Longoria: So, what about the question we started with? Like, in making the photo orange and bold, did Warhol transform the meaning of the photograph, like aesthetically?

Alyssa Edes: Right so, the Court kinda put that aside. They’re like we’re not art critics, we’re not hearing from art critics. We don’t want to focus on the meaning or message of a thing so much. We want to focus on how it’s being used.

So, in this way, they transformed their own transformative test.

And the reason why this technicality is interesting to me, is the Supreme Court had created standards for itself, a sturdy bridge, and then it just kinda changed the rules!

And they’re changing the rules based on their own understandings of the law, and their own preferences, their own biases, their own interests….

So, if art is in the eye of the beholder, Isn’t the law too?

Pierre Leval: No, no, no. No.

Alyssa Edes: Judge Leval.

Pierre Leval: It is definitely not in the eyes of the beholder. The beholder doesn't get to decide what the law is. And the fact that, uh, different people can believe that different cases should come out different ways, doesn't mean that, that there's no law and that everybody is just whatever anyone may think is what the law is. That's not what the law is.

[Record scratch repeating Leval’s “not what the law is”]

Jerry Saltz: To me, it's not a legal issue, it's a taste issue.

Alyssa Edes: We went to art critic Jerry Saltz after the decision came down. He’s all for artists getting paid, but he didn’t like the decision.

Jerry Saltz: The Andy Warhol case, for me, curtails art in an extremely dramatic way.

Alyssa Edes: That is basically what the dissent says too. Justice Elena Kagan writes, it will “stifle creativity of every sort.” Artists will hesitate to remix things! To get inspired! They won’t make new art. She thinks the decision will undermine the very thing the law was meant to do: advance the arts. And then, Kagan goes after the majority.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: She's essentially accusing the majority of being Philistines who don't understand high art.

Alyssa Edes: This is one of our legal advisors, Jeannie Suk Gerson.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: And she even says things like, um, this is art history 101, that they need to go back to school…

Alyssa Edes: And, in response, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority, hits right back. Sotomayor includes multiple footnotes.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: Long footnotes! Devoted to dissing the dissent. She says, “the dissent is a series of misstatements and exaggerations from the dissentant’s very first sentence to its very last.” Um, that's not normal. And some commentators have said, now at least we don't all have to pretend that everyone loves each other. But I don't know.

Alyssa Edes: Jeannie says compared to the past, this is a big shift in the Court.

Jeannie Suk Gersen: The idea that even if you disagree with the other side, you go to the mats on the substance, you don't go to the mats by engaging in personal attacks. I think that that era is drawing to a close, and we're seeing it very publicly in a Supreme Court opinion.

[music]

Julia Longoria: In the Warhol case, the passionate, personal disagreement that two Supreme Court justices are having out in the open is kind of wild. It kinda reminds you of two people disagreeing over whether a movie is any good or loving the song of the summer that someone else can’t stand.

Even though the judges say the law is nothing like art, think about the way art criticism often sounds.

Jerry Saltz: [mocking tone] The late capitalist post-structuralist post Marxian dialectic of the haptic…

Julia Longoria: They both have their jargon.

[Archive, Neil Gorsuch]: Factor three, which has to do with the amount and substantiality of the portion used…

Julia Longoria: Can you tell me like, what do you think makes a good art critic?

Jerry Saltz: Somebody that's willing to stay completely open. You don't decide beforehand what you're going to like. You don't say things like, “I don't like painting,” because of course you're going to see a painting eventually that you are probably going to like.

Julia Longoria: They’re both supposed to stay open, unbiased.

Julia Longoria: So, the best art criticism is democratic? It's a conversation?

Jerry Saltz: The best is everybody talking. Everybody’s putting in, everybody voting, everybody trying to convince the other and allowing as many stories as possible.

Julia Longoria: What do justices do when they try and interpret the law? The first time I ever stepped into the Supreme Court, it kinda felt like church. Like the justices were these servants trying their best to answer to a higher power of sorts. Maybe that’s a little bit self serious. But at least it seemed to me like they were reverent in front of the incredible stakes: the lives of the people in their hands.

If the law’s not like church, is it math? Like engineering a bridge, making sturdy objective legal standards?

Or maybe it is like an artform: impressionistic, ever-changing, imperfect.

[Archive, Male Interviewer: In other words, you have no vision of the past, no vision of the future trend, you're just doing whatever you feel like?

[Archive, Andy Warhol]: Well, yeah.

[music]

Julia Longoria: And that’s it for this season of More Perfect. We’re coming back with new episodes later this year. So, if you have questions about the Supreme Court, about the law in general, we want to hear from you. Go to MorePerfectPodcast.org and send us a voice memo!

Jenny Lawton: More Perfect is a production of WNYC Studios.

This episode was produced by Whitney Jones and Alyssa Edes, with help from Gabrielle Berbey. It was edited by Julia Longoria and me, Jenny Lawton. Fact-check by Naomi Sharp.

Special thanks to Sam Moyn, Jeff Guo, Andy Lanset, Amy Adler, Allison Orr Larsen, David Pozen, Jane Ginsburg, and Hank Willis Thomas.

The More Perfect team also includes Emily Botein, Emily Siner, Salman Ahad Khan, and Emily Madray. The show is sound designed by David Herman and mixed by Joe Plourde.

Our theme is by Alex Overington, and the episode art is by Candice Evers.

If you want more stories about the Supreme Court, we’ve got loads! Subscribe to More Perfect and scroll back for more than two dozen episodes.

Supreme Court audio is from Oyez, a free law project by Justia and the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Support for More Perfect is provided by The Smart Family Fund, and by listeners like you.

Julia Longoria: This is the last episode of the season, and there are so many people who made it possible.

Thank you from the bottom of our hearts to Miriam Barnard, Mike Barry, Aaron Cohen, Jason Isaac, John Passmore, Theodora Kuslan, Kim Nowacki, Andrea Latimer, Robin Bilinkoff, Rex Doane, Jacqueline Cincotta, Jennifer Houlihan Roussel, Dalia Dagher, Michelle Xu, Ivan Zimmerman, Lauren Cooperman, Kareem Lawrence, Rachel Lieberman, Maya Pasini-Schnau, Vanessa Cervini, Tara Sonin, Dan Fichette, Caitlin Quigley, Anne O'Malley, Liz Weber, Melissa Frank, Kenya Young, and Andrew Golis.

And thank you for listening.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.