Can America Be Redeemed?

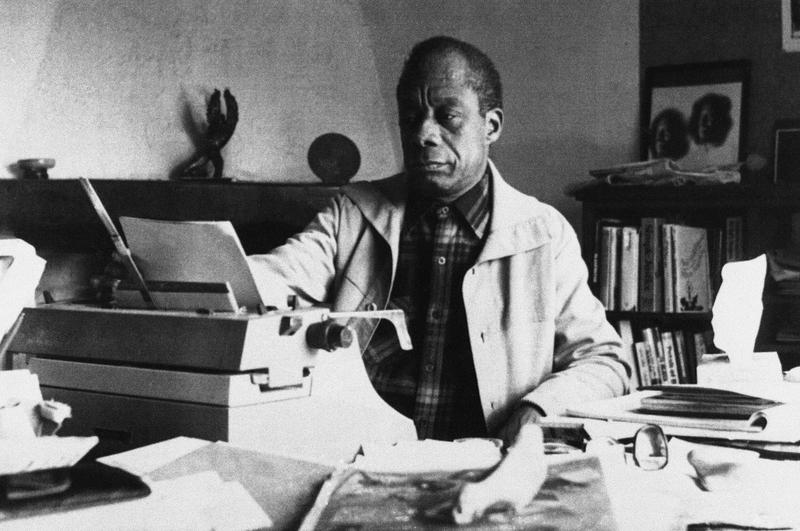

( AP Photo/Photo Pressenia )

Kai Wright: This is The United States of Anxiety - a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

Danielle Young: Y'all know we ain't celebrating the 4th of July no more, right? Independence Day.

Woman: There's nothing wrong with acknowledging the history and heritage of the land that you live in, but you better believe that what really made America great is the blood, sweat, and tears of my people.

James Baldwin: You can't swear to the freedom of all mankind and put me in chains.

Robin D.G. Kelley: We join the long line of Black thinkers who believe that to achieve freedom, we first had to get out of dodge.

Sequoria Dickerson: Through storytelling and holding space for folks to talk about the wholeness of who they are; the good, the bad, the messy.

Toni Morrison: Sometimes you don't survive whole. You just survive in part. It is about being as fearless as one can under completely impossible circumstances.

[music]

Kai: Welcome to the show. I'm Kai Wright. It's Independence Day. If you've been listening to this show for a while, you know that we often spend our holidays just kind of musing on stuff. I guess, if I'm honest, this is a pretty musing kind of show on any week, but we really let our minds wander on holidays because why not? They're supposed to be days of reflection, right? Actually, if you want to hear some of our previous holiday ramblings, you can go to our website at wnyc.org/anxiety and click on the Collections tab. There, you'll see one called On This Occasion. Click around. See what inspires you.

Anyway, on this holiday, I'm thinking about a very old debate in Black political thought. It goes all the way back to the early abolition movement, and it turns on a foundational question, "Is this America thing really worth the fight? Should we claim it and struggled to improve it, or do we conclude that it is rotten at the core and figure something out from there? Is this country redeemable?" Black thinkers have been weighing in from pulpits, and classrooms, and around kitchen tables on this question for centuries.

Myself, I'm kind of a book nerd, so I've really followed it through Black literature, particularly writing in the first half of the 20th century. That's a period where it's just like Reconstruction has ended and all the hopes and dreams of that is gone, and Jim Crow and all of its violence has set in; and there's all these writers, novelists, poets, essayists just trying to work it out, trying to figure out what is this American Project, where do I fit into it, and is it worth my trouble?

Two of the writers that really stand out for me in that time are Richard Wright and James Baldwin. That's because they are kind of in debate with one another about these questions - at least most explicitly in debate with one another - and they have very different takes on Black life in America and takes that are constantly evolving. In two newly published books, we're able to see that evolution. To watch as they try to work out their own answers to the question, "Is America redeemable?" One work is by Baldwin, a 1964 essay which Beacon Press has just republished as a short book; and one work is by Wright, a previously unpublished novel called The Man Who Lived Underground, finished in 1942 and recently released in full for the first time.

For this holiday, we got in touch with two of today's most acclaimed literary scholars. Imani Perry-

Imani Perry: I am the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University.

Kai: -and Eddie Glaude.

Eddie Glaude: I'm the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and Chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University.

Kai: Here's the deal. These two professors, you've probably seen them on TV or maybe even read their essays. They've been important voices in the racial reckoning where it's supposed to be having right now, but you should know that they are also, honestly, some of the smartest people on the planet about 20th century Black literature. James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Imani, and Eddie, have been reading and rereading these guys their whole lives. We thought, "Wouldn't it be cool to spend July 4th listening to them just muse with each other about these new books and these writers, and their thoughts on the American Project?"

[music]

Eddie: I'm a native of Mississippi, and Richard Wright, for me, was this example of what was possible. Here you have this guy, this man, who isn't formally educated, born in 1908 in Natchez, Mississippi, I believe, engaging in a sort of practice that was unimaginable. For me, Wright represents what's possible under captive conditions, to put on the page the depth and complexity of Black life. As a native Mississippian, he was a model of what was possible.

Imani: You all don't know this, but Eddie and Richard Wright have the same birthday, which may be irrelevant. I was born the day after, so that may be a little bit of a irrelevant piece of information. For me, until this conversation, I never thought about this, but I was a voracious reader as a child and I read Wright through - I mean, everything that I could find by Richard Wright - as a young person. I think I fell in love with Wright at the level of the incredibly beautiful sentences, the landscape.

I'm a person who defines my coming of age as spending much of it homesick. I left Alabama with my mother and moved to Massachusetts and was always yearning for the sounds of home and family. So, language, but also the landscape. He's so sensitive. Then I got the college, and everybody was like, "Wright is terrible."

Kai: Imani is referring to a long-standing critique of Richard Wright's work. He forced his readers to confront the brutality of racism and anti-Black violence, so the stories he told, the characters he crafted, they were often shocking with grim lives. Some people felt that led him to reduce the Black experience to Black trauma. That was the story about Richard Wright that Imani received when she got to college.

Imani: We had so much promise, but Richard Wright thought that Black people had no interior life, and so that was kind of a jarring experience. It was also the point at which I started reading Baldwin.

Eddie: Now, Baldwin is a whole different story for me. Wright let me know what was possible. Then Baldwin gave me the license to actually imagine myself in the most expansive of terms; giving me languages, words to describe the torrent of emotion that's inside of me, allowing me to think through my father, to understand my father's sense in relation to my own.

Kai: Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, it's a family story. It's not about racism or white people or any of that, not on its face. It's about a teenage boy coming of age in Harlem, trying to shake off the expectations of his parents and his elders. It opens with the scene of two boys alone in a church that's like-- I mean, I don't know what Baldwin intended, but if you've ever been a teenage boy unsure about your sexual orientation like myself and found yourself feeling moved in confusing ways, you may feel moved reading that scene, too. Anyway, the point is Baldwin's focus wasn't racist violence. It was Black life.

Eddie: It's interesting. Wright is 1908. He's part of the generation of that first wave of migration. Baldwin is the child of those folk because he's born in what? August of 1924. Baldwin wants to keep track of the interior life of Black folk and the material conditions. It's not an either/or for him. What does it mean to give voice to the complexity of what it means to be Black in a world that is shot through with assumptions about our value or lack thereof?

Imani: I think for me, what both of them do for me, even if I disagree sometimes with the conclusions that Wright draws about the meaning of Black life, is they each mastered how to make points about the political economy, about white supremacy, about gender and violence, without-- They could do it in narration. They didn't have to announce that they were making these points. It's a mastery of form that I think is actually necessary for a reader to be moved enough to be convinced of an argument at a deep level.

Baldwin also figured out how to write in the first person and not be narcissistic and not be self-involved. He'll tell you a story, he's in there, and you're not thinking, "Oh, why is he talking about himself again?" Your thinking is, "I get to see the inside and it resonates with something that I feel inside," so you invest.

[music]

Kai: The problems Baldwin and others had with Richard Wright's work mostly grew out of his most famous novel, Native Son, published in the spring of 1940. It tells the story of Bigger Thomas, who is one of the most notorious characters in literature. He's a young Black man living in a grotesque slum. The book opens with a graphic scene of him killing a giant rat in his family's one-room flat. It's gross and you immediately get the point, this is a subhuman existence.

Bigger is an emerging gangster who gets himself into a complicated situation where basically he decides to commit the unthinkable Black male crime; he kills a white girl. The whole story just gets darker from there. He becomes the Black goblin that white America imagines.

Eddie: What happens when we think about Black life in this way is that we're not dealing with the human being on the page. That something gets lost about the depth of complexity of human doing and suffering. There's more than just simply rats and hatred and anger. Although that's there, but also there's more.

Imani: Ed, here's the thing that I struggle with, is, one, Native Son is this unbelievable runaway success. Book of the Month club. I mean, kind of unprecedented and unexpected. So, Bigger becomes a representative figure as opposed to a mere character. This is a Black man's story that the whole country is reading; and clearly, the dominant emotion for me through Bigger is fear, terror. He is terrified. He doesn't work, obviously, as a representation of Black subjectivity overall, but I do think he's interesting as a character in a way that is more complicated than I think we have often treated the novel precisely because of the prominence of the novel.

I think that Richard Wright failed in his aspirations with Bigger because he aspired to create a character who would not elicit sympathy. In some ways, he's the opposite. He doesn't want you to feel sympathy for Bigger, but Bigger is an emotionally compelling character whether Wright wanted him to be or not. I actually think his skill undermined some of his intention. It's hard to imagine that the book would have been as successful as it was if there weren't some degree of emotional resonance in the character.

Eddie: Right. Maybe that's why The Man Who Lived Underground didn't get published because the absence of sentimentality in that text, right?

Kai: Richard Wright sent his publisher a draft of his new novel, The Man Who Lived Underground, just a year after Native Son came out as that big hit, but it's a very different book and he could not get it published in the 1940s, not as a full novel. It lingered in the archives all the way up until this spring.

Coming up, Eddie Glaude and Imani Perry shared their reactions to the new book and to a newly republished work of James Baldwin as well. What do these words still tell us about America in 2021? That's next. I'm Kai Wright. This is The United States of Anxiety. We'll be right back.

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright. This is The United States of Anxiety. This week, we've invited Princeton University scholars, Eddie Glaude and Imani Perry, to talk to each other about the works of James Baldwin and Richard Wright; two massive figures in American literary history, each with disturbingly prescient work. Beacon Press has just republished Baldwin's 1964 essay, Nothing Personal, as a small book with commentary from both Imani Perry and Eddie Glaude.

A novel Richard Wright submitted to his publisher in 1942, The Man Who Lived Underground, has finally been released in full for the first time by the Library of America. It's a story about a striving working-class guy who is falsely accused of murder and then beaten senseless by the police. He escapes and he slips underground, literally, into this surreal existence in the sewers below the city. In his previous novel, Native Son, it seemed as if Richard Wright wanted us to look at his Black protagonist with horror and revulsion. Now, in this story, we're to empathize with Fred Daniels and learn from him, not just about the hypocrisies of racism but of capitalism.

Imani: The Man Who Lived Underground is so interesting because in many ways, you begin with someone who is very clearly not of the Biggers of the world. He is respectable. He goes to church. He's decent. Then he has this encounter with police violence and sort of is in disbelief. He is in disbelief that he's been falsely accused, he is in disbelief that they beat him, so it's in some ways the other side. I mean, the sense that Bigger has done the thing, Bigger has committed the act. This man has not and he suffers brutality. It has this remarkably prescient quality to it.

Eddie: Absolutely. When I've picked up this new edition, I started reading it, I had to put it down. I couldn't. It's too much. Because it was this moment where we were grappling with all of this death at the hands of the police. I remember pouring a triple of Irish whiskey of Jameson. I was 10 pages, 20 pages in, and I said, "I can't read this right now." It was just too close to home, it was just too close to me.

There's a sense in which the ongoing betrayal, the layered betrayals of the American Project vis-à-vis Black folk, has demanded, has required an experimentation in form. There are these moments in the novel that just didn't work for me, but then I just, "Well, wait a minute. This is purposeful. This is not this kind of mirror reality. This is something very different."

The first part of the novel is this as realistic rendering of the encounter with police brutality as you can get. Once he goes underground, it's allegory. Whether it's unseen labor with the white face that you can't see that's shoveling coal, whether the theological arguments he's making.

Kai: What happens is the character basically roams around observing daily life from underground, watching people work and buy things and go to church, and he's got a different lens on all of it now, now that he's viewing it from the sewer. He can see the absurdities and hypocrisy and cruelties with more clarity. As his own journey gets more fantastic and unreal, as readers we also start to kind of lose track of what's real and what's not in the story, and maybe also gain some clarity as a result.

This novel was an evolution both in what Richard Wright had to say about the American Project and how he said it.

Eddie: What does it mean to get on the page? What it takes to navigate this shit? What does it take to figure out what's happening in the gut and to find the right language, the right sentence, the right form, to get it on the page?

[music]

Kai: By the time James Baldwin writes his essay, Nothing Personal, in 1964, he, too, has been hardened by the brutality of American racism. He can no longer just talk about Black life, he's forced to speak directly to white violence. He's writing just after his friend, Medgar Evers, an NAACP organizer in Mississippi, has been assassinated in the driveway of his own home; and his perspective starts to sound a lot more like Richard Wright's.

Eddie: Nothing Personal is like the railway switch. It's announcing the shift, the change from the early Baldwin in the life, because he's grappling with the fact that Medgar is dead. That the promise of the Civil Rights Movement is already revealing itself to be imperiled.

Imani: Overwhelmed by grief, death, death, death, death.

Eddie: Overwhelmed by grief, deeply paranoid for good reason, surveilled in ways that are unimaginable for many of us. The state looming in their lives, not just the state as such but the repressive state apparatus. Yes, so this place may not be redeemable, but neither, I think, would say that we are irredeemable.

Kai: One of the most powerful images Baldwin draws in Nothing Personal is that of America being trapped in a self-destructive adolescence, refusing to mature.

Eddie: There are ways in which I read Baldwin's kind of invocation of adolescence in a number of different ways. Because he wants to say that those who cling to adolescence become monstrous because they, in some ways, refuse to grow up. When he says they refuse to grow up, that means they refuse to be responsible for anything, they refuse to be held to account. So, America has this feeling of never-never land, full, populated with lost boys and lost girls.

Imani: We all grow up with the discussion, the United States of America is a young nation. I came of age with every year you read Douglass, What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? It becomes a kind of charge of the mythology, the betrayal, the way in which white supremacy was embedded in the structure of the nation-state, and Douglass is challenging Americans on that question. But now, we live in the era where we have Juneteenth is a national holiday, and Black History Month, and you can get Kwanzaa cards at the drug store by your house. Commemoration has been diversified, and yet the core has not been shifted in so many ways.

Eddie: I think all great literature help us understand what happens between the two momentous breaths we have. You have two momentous breaths, the first one and the last one. What happens in between? There's something about what it means to make this journey in this particular body, in this particular place. The Man Who Lived Underground and Nothing Personal offer some insight. All great literature, to my mind, offers a window to understanding what it means to make your way through time and space.

The central contradiction in this place has been, and continues to be, the way my folk - the people I care so deeply about - are subject to the whims of such absurdity over and over again. So, it makes sense to me in this time that these two texts would reemerge. That we would begin to return to that canon, that literary tradition that seeks to make sense of this place.

What does it mean to read Nothing Personal? What does it mean to read The Man Who Lived Underground? These are not only resources to help us make sense of what to do between those two momentous breaths, but they're also repositories of a kind of counter-memory that offer us resources to not only make sense of the world we inhabit but also to imagine changing it, to imagine transforming it, and to imagine ourselves otherwise.

Kai: That was Princeton University professors, Eddie Glaude and Imani Perry, in conversation about two recently published works by James Baldwin and Richard Wright. Imani mentioned that she's of a generation that grew up reading Frederick Douglass on July 4th. That is me, too. Douglass was an enormously popular orator in the years leading up to the Civil War. He traveled the world talking about America's failure to live up to the ideas described in the Declaration of Independence.

In 1852, the Rochester Ladies' Anti-slavery Society invited him to speak at an event commemorating the signing of the Declaration. The address, which he delivered on the July 5th of that year, it is still considered one of the greatest pieces of oratory in American history. Ever since I learned about it back when I was a teenager, it's been part of my own July 4th ritual. I sit down and I read it, and I remind myself of just how many generations of Black people have fought for my place in this nation.

Since I've become a radio guy, I've been finding ways to broadcast it on July 4th, too. So, here is this year's rendition. Actor John Douglas Thompson delivering the climactic section of Frederick Douglass's What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

John Douglas Thompson: What to the slave is the 4th of July? Fellow citizens, pardon me and allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? And am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess their benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary. Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This 4th of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice. I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me by asking me to speak today?

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is a constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy - a thin veil to cover up crimes that would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation of the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of these United States at this very hour.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. Oh, had I the ability and could reach the nation's ear, I would, today, pour out a stream - a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and the crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

[music]

Kai: That was actor John Douglas Thompson delivering part of Frederick Douglass's famous 1852 speech, What to the American Slave Is the Fourth of July? Coming up, our holiday musings turn to the future. James Baldwin said America was stuck in adolescence, refusing to grow up. Arguably, big stressful moments in our history have fueled some growth, though, and maybe the past year and a half will foster a new era of maturing. We'll talk with a social psychologist about the idea of post-traumatic growth. That's next.

This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. Stay with us.

[music]

[advertisement]

[music]

Kai: Welcome back. This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. This spring when I spoke with jazz composer, Jason Moran, for our Memorial Day show, he said he believes, maybe hopes, that jazz is about to enter into a renaissance of sorts as people come out of a year-plus of isolation and, for many, a political awakening. I wonder if that's going to be true more broadly for all of us in this next period of our lives. If something new that we don't yet understand will come out of the pressure cooker of the pandemic and the election and all the rest of it.

We reached out to someone who has studied what happens to our minds and our spirits when we go through these intense situations. Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis is a psychologist, a minister, and an artist. She's a professor at Pepperdine University and host of a podcast called The Homecoming. She has researched extensively how we react to and recover from trauma individually and collectively. Dr. Bryant-Davis, thanks so much for joining us.

Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis: Thank you so much for having me. I'm excited for the topic, and it is so important as it's affecting all of our lives.

Kai: Right. Well, so let's just start with history. We spend a lot of time on history in this show. When you look back at the 1918 Spanish flu, and World War I, and it's followed by the Roaring Twenties - this time of eruption. We look back at the bubonic plague, and it's followed by the Renaissance. There does seem to be this history of awakenings. What is actually at work collectively, and is there a way to explain the psychology of the moment?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Yes. Some creativity comes out of our pain and our wound and, in some ways, the arts give us language for the things that seem unspeakable or even unbearable. What trauma is, is a source of stress that overwhelms your usual capacity to cope. Then there are these life events that are disruptive that make us have to reorient ourselves, and so a lot of people's artwork comes out of that place and innovation comes out of that place. As I look at thriving in a post-pandemic world, one of the keys is integrating the expressive arts. They are healing, and it creates a space for us to both reflect what is and also what can be.

Kai: Right. We're in this moment where, yes, our lives are totally different today than they were a year ago and certainly a year before that, I guess, but there's this tension between the tremendous sense of loss that many of us are carrying around and this jubilation as we pour into the streets with our communities again. Just psychologically speaking, what is happening here? What are we experiencing as individuals and collectively in this moment? How would you diagnose it?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: It is so important to hold both realities, which is the stress and trauma that we have faced and are facing, as well as the growth and the possibility of thriving not only surviving. And each of us will hold those two tensions in diverse ways. Some people are still really dealing with depression or grief. We've had both tangible losses of loved ones and also intangible losses like time, or work, or graduations, or anniversaries that were missed. We also have the level of anxiety - thinking about the name of this show.

[laughter]

Kai: Right?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Then we have both the worry for ourselves and also for our loved ones, and people wondering about the future. What is going to happen in the fall, in the winter? One of the things that people often are not aware of is something called post-traumatic growth. Not only do we have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and that really came into being thinking about veterans, but it has expanded beyond that to all of the different ways that distress shows up in the aftermath of trauma, but we have also documented that many people experience a growth in the aftermath.

Kai: That's a new phrase to me. I think many of us are familiar with PTSD. Post-traumatic growth then. What is that?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Post-traumatic growth are the ways in which we can experience a sense of enhancement, new knowledge, new awareness, new skills, in the aftermath of traumatic events. We attribute it to the individual and their support systems, not just to the trauma itself. That distinction is important because if not-- Some people will say things like, "I'm glad this horrendous thing happened. It made me a better person." Well, there are people who have horrendous things happen that don't emerge feeling like a better person. But when we have the supports and the resources, both psychological and social, sometimes economic or political, we can actually come out of experiences with, what I say, pulling the wisdom out of the wounds.

There are different categories of growth. One of them is a greater appreciation or gratitude for life. Things that we used to take for granted like going to church, or going to see your parents, or your children having a playdate, that we didn't think anything of, and now it's like, "Oh my goodness," right?

Kai: Right.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: This really valuing of people and relationships and time. Another one is around skills. Some things we didn't know we knew how to do, and we figured out how to do over the course of this year. I know when the pandemic started, suddenly all of the baking aisles were empty. People were trying to figure out how to make new things [crosstalk]--

Kai: Baking bread.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Right, and doing it with family or doing it alone, getting innovative with technology. I mean, who knew we could do memorial services online? It stretched us and caused us to learn new ways. One of the communities that have really spoken up is the disabilities community that says, "These are changes we have been asking for for years, and so many people said it was impossible." Now, we developed it because more able-bodied people needed it, and so advancing our possibilities.

Kai: How do we know that this growth that you're describing, these experiences are things that will linger? Because this is the conversation so many people are in right now, you hear and you're like, "Yes, I learned how to control my time better over the course of the pandemic," or, "I learned how to value my relationships more," and already three weeks later, you're going to forget it. Help me understand the line between the things that we say rhetorically to ourselves and what we actually know in the science and in the psychology about what can last.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: That's why it's so important that they've also done longitudinal studies. Because as you're naming, if you talk to someone the week after an earthquake, then it's so much gratitude of, "I'm so glad we made it out of there." Then one of the things that has even been said about us in the US is this amnesia, this lack of really understanding or appreciation of history, but we do have the capacity to have this long-term growth. A part of what helps that is going through something as a society or something that affected so many people.

It's hard to hold on to a change when everyone else around you has not shifted at all. You hear so many people, as you have said, talk about, "I'm not so much wanting to go back to business as usual. The way I was living before was so frantic and so much in the grind and hustle-" [crosstalk]--

Kai: Unhealthy, like killing us.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Right, it really was. I know for myself, it even has shifted my idea of the weekend. Before the pandemic, for me the weekend in some ways was busier than the week. Going here and there, doing this and that; and suddenly, really understanding Sabbath, or mindfulness, or the sacredness of stillness, or enjoying those simple pleasures in your own home. Because this has sustained over time, I think you do have people trying to pace themselves a little bit more.

Kai: Yes. If part of what makes it last is that everyone experiences it, that there's a collectivity to it, are there things that you see happening or that you think should be happening on a social level? Now, I'm thinking about government, I'm thinking about employers, that people who shape our collective experiences, that will help the post-traumatic growth happen and last?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Yes, definitely. You see a lot of companies looking at different ways of doing the work. People have, for the first time, actually been sending out polls asking the employees - and again, it depends on your field - what they are comfortable with, and trying to be mindful that people should not have to disclose their health information because you don't know who was taking care of family, or the losses people have had.

From the government perspective, I think one of the pieces that has been so important is highlighting mental health. As opposed to before, psychology was kind of knocking on the door trying to get the public to notice it. In these times, we see so many more, from government officials to parents, who are reaching out saying, "What can we do? We know that we have been affected."

Kai: Well, that's heartening that you are seeing that. That is heartening. That, in fact, you're seeing from policymakers a more receptiveness to the idea that we have to deal with our mental health.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: That's right. Historically, I think so much of the attention was focused on physical health and then the legal piece, mental health was often left off of the agenda, but I think there is so much of a greater awareness. During the pandemic, so many of us mental health professionals got filled to capacity because so many people were needing the supports.

Kai: In your podcast when you're talking about post-traumatic growth, you refer to people, you say, are on the journey back home to ourselves.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Yes.

Kai: What do you mean by that? It sounds like it's something along these lines.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Yes, definitely. The stress and busyness of life and trauma often disconnect us from our authentic selves. It can cause us to chase material things, other people's approval, and we can look up and years have passed of our lives, and we actually miss ourselves. We miss who we are. We're so busy chasing. To come home to ourselves is to be able to radically accept who we are without performance, and to be authentically that person no matter where we are or who we are around, and that is liberation.

Kai: Your work is particularly rooted in a womanist perspective. You have done a lot of work in Black communities, in communities that are othered in various ways in our culture. Certainly, the pandemic has hit us harder than others. These things you're thinking about in terms of post-traumatic growth, how does it play out uniquely from that perspective?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: For those who aren't familiar, a womanist theology and womanist psychology comes from the wisdom and the experiences of Black women. It is important that those who have been marginalized really are central as we think about health wholeness and wellness, in part because we are disproportionately affected by these traumas. So, having higher rates of death by COVID-19 and then of course, the additional trauma of racism as well as other forms of oppression.

For me, what that means is if I recognize that certain sources of stress or trauma affect particular communities more, then I have to be intentional about addressing the needs of that community. That some are facing a heavier weight of the grief and loss and, at the same time, recognizing that these communities - including the Black community - hold cultural resources, ways of healing and growing. To recognize both the trauma and the tragedy in our communities, but also the strength, the triumph, the resilience, the wisdom.

The beautiful part about our work is culturally informed or culturally emergent interventions that really honor and integrate our culture, whether that is including our proverbs or sayings, utilizing our music and dance. So, I'm excited about those possibilities as well.

Kai: One form of post-traumatic growth might be racial justice?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: That's right.

Kai: Racial justice particularly would be a welcome piece of growth.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Yes, definitely.

Kai: Earlier in the show, we heard a conversation about James Baldwin and Richard Wright and their sort of future-thinking of their era. There's so much of their work we read now that it sounds like it was written in 2021.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: That's right.

Kai: It makes me think about memory. Help me understand the psychology of our memory in general. How does that work?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: One of the important things to know is that traumatic memories, neurologically, physiologically, are difficult to retrieve. Often when people are saying, "I don't want to talk about it," it is not only an emotional block, but even the challenge within the brain of going to that place, pulling it out and then to verbalize it.

One of the things that can be really helpful when we think about memory is something called narrative psychology and liberation psychology, which comes out of Latin America. They have something called testimonials, which is similar to, in the Black church, the testimony service, telling your story.

Kai: Right.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: What we help people with is centering themselves in their story because sometimes the way we have encoded and told our stories, we are like side characters without agency or voice. When we are healing, it is not only about what was done to me, but what is the story I want to write? There are some things that happened on the pages of my life that I did not have a say in, but I also do hold a pen. It is being active as we are co-creating our life story. We just discover the more I look at it and the more I speak about it, the more I tell the story, the more liberation I can feel.

Kai: There's a lot of that happening right now, which I think about the explosion of memoirs and podcasting and people trying to document their moment. All this citizen journalism in some ways.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: It's beautiful.

Kai: Yes. Then out of all of that, you're looking at people doing that kind of thing. You're looking at the changes that are happening in the medical field. Where do you think we're going?

Dr. Bryant-Davis: I think there will be those who really hold on to the shift and are kind of trailblazers in this time, and there are those who will really be struggling even as we declare the "aftermath" or on the other side of this. I think it's important that we have compassion and understanding and release judgment about where everybody is in this.

Because one of the things that we noticed in the beginning of the pandemic, some people were doing this thing of saying, "We have all this time on our hands. We need to write books, learn an instrument, learn a new language." For some people, it was like, "Can I get out of bed and brush my teeth? If I could do that--" So, I would say to have grace and compassion for where we are in the journey. I do think we will hold a greater level of sensitivity for the untold stories of what people are walking with, and I see greater truth-telling on the other side of this.

Kai: Here's to both of those things.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Yes.

[music]

Kai: Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis is a psychologist, a minister, and an artist. She's a professor at Pepperdine University and host of the podcast, The Homecoming. Thank you so much for this.

Dr. Bryant-Davis: Thank you for having me. I really enjoyed it.

[music]

Kai: United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Some special thank-yous are due for this episode. John Douglas Thompson gave us that gripping performance of Frederick Douglass. Thanks to him, and to Sam Bair, and the whole team at the Relic Room Recording Studio. Also, thanks to Aisha Turner for some editing help this week. Jared Paul mixed the podcast version. Welcome back, Jared. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Carl Boisrond, Emily Botein, Karen Frillmann, Gigi Polizzi, and Christopher Werth. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. Veralyn Williams is our executive producer, and I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright, and I hope you'll join us for the live show next Sunday, 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it at wnyc.org or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC.

Until then, thanks for listening. Take care of yourselves.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.