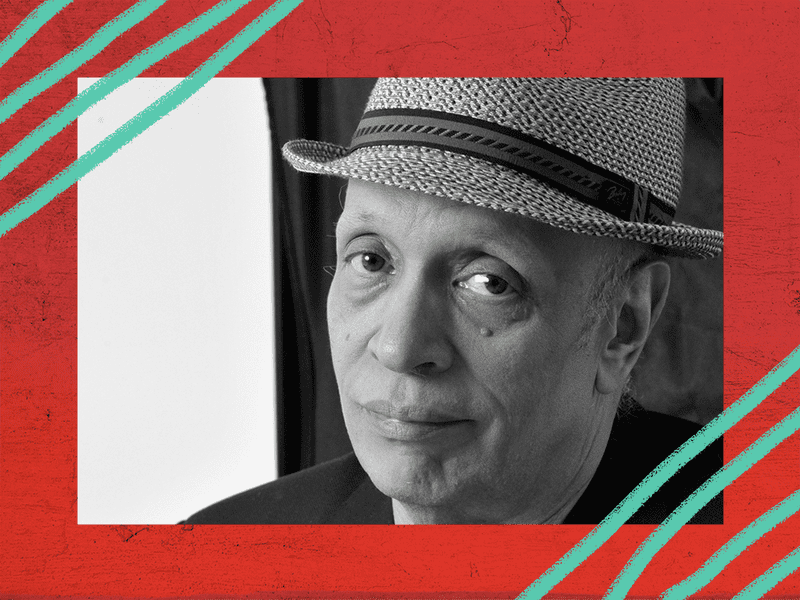

7. Walter Mosley Believes in Freedom of Speech. Period.

Just a quick heads up to listeners - this episode does feature the use of the N-word.

I’m Rebecca Carroll and this is Come Through: 15 essential conversations about race in a pivotal year for America.

Last fall I had a conversation that really crystalized for me why I wanted to make this podcast. Because, when we're addressing issues of race, there’s a ton of nuance in play and I want to interrogate that, all the time. Like, this episode which asks, “Where do you draw the line between free speech and a racial slur?”

So here’s the backstory: last September the author Walter Mosley wrote an op-ed for the NYT called “Why I Left the Writers’ Room.”

And in that piece, he tells the story of an interaction he had while he was on the writing staff of the TV show “Star Trek: Discovery.” During a meeting, he shared a very personal story in which he said, and I’m just going to say it here, the word “n-gger.” The word was an integral part of the story — it was THE story. But it made someone in the writers’ room uncomfortable, and that person reported Mosley to HR.

Now, even before I invited Walter Mosley into the studio to do an interview, I knew that I have a very complicated relationship with the N-word. But I didn’t realize just how complicated until we started talking, and things got pretty tense.

Because I suddenly realized that my feelings about the word have evolved in this really complicated and marked way from when I was a kid growing up in all-white New Hampshire. When I heard it the first time, it was directed at me in its cruelest iteration by other kids; and later, when I was a teenager and was working an after-school job, my boss called me the N-word too.

Being called “n-gger” was a trauma that felt like being yanked out of my parents’ arms and dropped into this dark pit. Which I know is really dramatic-sounding, but, in truth, trauma can really kick your ass. And so when I heard that word, I was forced to just sit alone, knowing the security of my parents wasn’t enough. Or worse, that the security of my parents was a lie. This word, it felt, was something that they could never know as white people, or protect me from.

In retrospect, clearly this was connected to my fear of abandonment as an adoptee.

When my son was in third grade, probably about the same age I was when I heard it the first time, he asked me about the word unprompted.

We were in the car, and, out of nowhere, he asked me, “Mom, would it be okay if me and my friend said that word to each other, just between us?” He didn’t say the actual word — as if he could sense my apprehension around hearing him say it.

The truth was then, I didn’t know.

A few years ago, Ta-Nehisi Coates was a guest on the podcast Another Round, and during what the hosts called “The Rapid Fire Question” segment, he was asked about his favorite cuss word.

Ta-Nehisi: I mean, n-gga.

Tracy: Okay, you consider that a cuss word?

Ta-Nehisi: I think most people do. It's the type of thing you don't say in public company.

Tracy: Huh-huh.

Heben: That's true!

Ta-Nehisi: But n-gga is a great word.

Tracy: It's the best word.

“It’s a great word,” he said. And he and the hosts, also both black, laughed together and had this moment of shared, sacred joy. It was such a pure display of black community that it made me wish I could feel the same.

All this to say that after I read Mosley’s op-ed about his experience in the TV writers’ room, I really just wanted to talk with him. I wanted to really explore what makes me and others so uncomfortable about the N-word.

Walter: So you want to hear the story and in detail I can, I can use the language of my, the story.

Rebecca: You can do that.

Walter: Okay, good. Uh, years and years and years ago in Los Angeles, I was walking down the street and I was a kid and a policeman stopped me. And the policeman said, you know, he searched my pockets. He asked me questions, he searched my pockets again. He asked me more questions and finally he said, “Okay, you can go.” And I said, “Excuse me, officer, may I ask you a question?”

He said, “Well, yes. What is that?” I said, “Why did you stop me? I mean, I was just walking down the street. I mean, I'm not doing anything.” He says, “Look. If I see a n-gger in a Patty neighborhood, I stop him. And if I see a Patty in a n-gger neighborhood, I stop him because they're almost always up to no good.” I just told that story.

Rebecca: Where was this?

Walter: It was in a writer's room.

Rebecca: No, no, no, no, no. I mean, where did this, that happen to you?

Walter: Oh, Robertson, Robertson Boulevard in Los Angeles.

Rebecca: Okay, okay.

Walter: And so I was telling the story. Next day I get a call and they say, “Oh, excuse me, Mr. Mosley?” And I said, “Yes?” “You're Mr. Mosley?” I said, “Yeah.” He says, “Well, this is HR, and it's been reported that you use the N-word, which I think is worse, uh, in the writer's room.” And I said, “Well, you know, I am the N-word in the writer's room.” And they said, “You can't use that word. You can't use that language. You could write it in a script if you want, but you can't use the language. You can't say it.”

Rebecca: And so how did this person make that decision that it's okay to write it but not okay to say it?

Walter: Well, listen, in all certainty, I can't answer that question, but he has a boss and they have a boss and they answer to the people on the top. The people on the top said,

“We don't want to get in trouble. You know, if people start to sue us because of a, an unfriendly work environment…” And so these are the rules.And these are the rules that everybody has to follow.

Rebecca: Okay. For a moment, let's just look at how that could have created an unfriendly work environment. Did you ever find out who was made uncomfortable?

Walter: No.

Rebecca: And is there any feeling or sense on your part of wanting to know who that person is?

Walter: Well, I, you know, I'm not dying to do it. I guess I could start asking a lot of people to try to find out. But I don't care. You know, because the problem is not... You know, somebody feels uncomfortable and they feel well... When I feel uncomfortable, I can call human resources and human resources can do their McCarthy-istic-like thing and say, “Someone has said they're uncomfortable.” And then they said, “You know, they don't want you to be in trouble.” And I said, “But I am in trouble, right?”

Rebecca: Right.

Walter: And they went, “Well, yeah, I guess if you want to look at it like that.” And I said, “Well, you know, you're threatening my job, right?” And they go, “Well, only if you keep, you know, uh, expressing yourself.”

Rebecca: It was interesting to me in your piece that you focused… You placed the word more in the context of freedom of speech, than on the sort of racial ramifications behind who can and cannot say the word. And so let me just ask the question. Is the use of the word, this word that has been more weaponized than any other racial slur in the history of America, constitute freedom of speech? For who?

Walter: Well, look, I believe in freedom of speech in America, period. And as I said in my op-ed piece in the, in the Times, New York times, that people came up to me and they said, “Uh, will you, you know, sign on to make the Confederate flag illegal?” And I said, “No, because we have freedom of speech.” People could say, you know, what they want to say. They can love the flag.They can hate the flag. I don't like the flag, but I'm not going to go tell somebody else that they can't, you know, if they identify with this flag that they can't use it. I mean, you can't put it in a, you know, in a, in a public place if it doesn't belong there. Um, but. So, you know, and, and people have asked me, said, well, what if a white person had told that story? I said, “Well, you know, listen, the white person could tell that story.” They said, “Well, what if you felt uncomfortable?” So, “Well, you know, feeling uncomfortable is a part of free speech.” People saying things is part of free speech. Women saying, “Uh, I have the vote.” People saying, “I have the right to same-sex marriage.” Anything that you say, you know, might make somebody uncomfortable. It might make me uncomfortable.

Rebecca: But this would not have happened if you weren't black.

Walter: No. I think it would have. I think if a white person had said the same story I said and somebody heard it and complained, they would be in the same situation, maybe even worse than me.

Rebecca: Provided there would have to have been other black people in the writers’ room, right? So.

Walter: No, I'm not. I'm not even certain of that. I think that all kinds of people have all kinds of reasons to be uncomfortable and I'm not trying to define, “Well only white people do this, and only black people do that.” I think that anybody can, can complain. Say, “I was made uncomfortable when this person used this language.” And I think that the human resources department, they are primed to respond to the complaint, not to the race of the person complaining or of the person they're complaining against. I think that it can happen to anyone, and I think it's a problem for everyone, you know.

Rebecca: But when is the usage of the N-word... I use the N-word because, uh,

Walter: You mean, you say n-igga?

Rebecca: I was raised by white people and I was attacked by white peers, and that word was thrown at me in ways that I, I don't feel like I want to use it. Okay.

Walter: And that’s fine.

Rebecca: And so that's why I say. But when is it so, so I'm asking you, when is it used by white people, that it's not racism?

Walter: If somebody had told the story I told, it wouldn't have been racism. They would have said, “I had this experience. I was with my friend.” Because I’ve spent it with friends and the same things have happened. White friends. And somebody said it and they said this, and they said that. If you are, uh, harassing somebody, if you are bullying somebody, if you are, humiliating somebody, any language that you use becomes problematic. And there needs to be a discussion. However, there needs to be a discussion. You don't need to be called by Big Brother on the phone. And Big Brother says, “If you do this two more times, you'll be fired.” The same person who talked to me said, “If you use the C-word, we would fire you like that.” And I'm like, “Really? So if I use the word, you have the power to fire me, even though I have freedom of speech.” And he said, “Absolutely.” What, what, what, what? What am I gonna say to that? That's wrong.

Rebecca: So…

Walter: It's just, it's just wrong. I mean, I could see where if I was attacking somebody, if I was calling somebody a name, if I was doing something that there would have to be a discussion about it. Because you know, you have to have a work environment that actually works. But the idea that people can start to make a, you know… That people who are like way above me, who have like, you know, have all this money, all this power who are worried about getting sued. They're making decisions. They're not making decisions ‘cause they care about the use of the word. Like for instance, when I said the story, a n-gger and Patty neighborhood, Patty and n-gger neighborhood, nobody questioned the use of the word Patty. Nobody. And that's also, that's also a racial slur.

Rebecca: Right. It’s not as weaponized as...

Walter: But it doesn't matter.

Rebecca: Why doesn’t it matter?

Walter: Because this is the language that belongs to us. If we're going to use the language, we're going to complain about the language. Because you know, there are a lot of Irish people who really feel very insulted by that word and who hate it. Now you might say, “Well, it's not weaponized.” But they're going to say, “It is. This is very insulting.” And if you look, you know, online, all the people who responded to the thing I wrote, a lot of Irish people saying, “Well, how come nobody said anything about that word? That word insults me. It asserts my people, my history in America.” And I'm going, “Yeah, you're right, it does.” And like, why didn't anybody say anything about that? Because they, ‘cause they're not worried about us being sued over that word. That's why.

Rebecca: But you said if I were bullying or harassing or…

Walter: Yeah.

Rebecca: So, isn't that subjective? I mean, when I hear that word uttered out of a white mouth I feel harassed.

Walter: Well, and, and that might very well be. But if the intention of the person saying it was not that, I mean, you have to worry about all of those things. You know, it's like, look, I was, I was, I once worked in a, I was a nighttime custodian. It was like me and like 12 other guys. 11 of them were young black men under the age of 21. And we went to this school. And, uh. A white, older white woman. I mean, really, she looked ancient to me when I was 21 but I think she's probably like 60 and she came out and she saw all of these, you know, powerful young men standing in front of her and she went, her face lit up and she said, “Oh, I'm so happy that you boys have come to help us clean the school.” One of our guys from Arkansas, we, it took the other 11 of us to stop him from killing that woman. Because she used the word, to her, completely innocently. She's 60, we're 20. She sees us as boys, you know. I mean, that's how she saw it. She had, she had, you know, she's not from the South. She had no idea of, of, of, of the racial intention of, of that word, you know, which was certainly weaponized at, at that time.

Rebecca: She had no idea.

Walter: She had no idea. She was so shocked. She was like, “What happened?”

Rebecca: I don’t believe that. I don’t.

Walter: You don’t. I do. I was there. I saw her, I saw them, I saw him.

Rebecca: In the south?

Walter: No, this is in Los Angeles, you know? No. If she was in the South, yeah, yeah, of course. But she, we weren't in the South and she wasn't from the South, but, but the, but the point was, is that it wasn't even what she said. It was how this guy, this guy's whole world could have been destroyed by interpretation he had. There's no moment of him to be able to think about it. He was just like, “I'm going to kill this 60-year-old woman.” And it's like… And you know, we stopped him. You know, we held him. I mean, I had an arm, somebody else had an arm, somebody was around his torso. I mean, he was a strong guy.

Rebecca: Isn’t that different from freedom of speech? I mean, the stakes in that story are so high.

Walter: But she didn't even know it. I mean, what I'm saying is, you know, I live in a country where freedom of speech and the right to pursue happiness are the highest goals of the country. I live among a people who have been in this country since the beginning of this country. You know, leaving out Native Americans. We've been here forever. This is our country. We've helped to define this country. We built this country. And, you know, I'm not going to get mad at somebody who says, “Well you got a Confederate flag.” I'm glad that I get to see your Confederate flag ‘cause I know who you are and what you are. I'm glad to hear you say what you're saying because I know who you are and what you are. And I myself have to say, “Well, there's some things that I have to endure, like my president talking.” You know, because yeah. Well you can say things. The president on down, it doesn't bother me. So my argument was, you know, more to my union, you know, the Writers Guild of America saying, “I'm sitting in a room, I get to say what I want to say.” If indeed I'm in conflict with you, and then I start calling you names. That's, that's a different thing. That is a different thing and that has to be dealt with. And if I continue doing it, they might actually have to say, “Listen. We can't have you in this room because you're causing too many problems on purpose.” But me just telling them the story, I just told this story. I didn't expect anybody to get mad. I wasn't expecting somebody to come back and complain. And by the by, I'm not the only black person in that room, so it could be a black person who complained against me.

Rebecca: Okay, it was reported in several cases that you were the only black, right? In that room.

Walter: But they were wrong.

That’s Walter Mosley - he’ll talk about the difference between what we say and what we mean - in just a minute.

Rebecca: So Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote a piece in the Hollywood Reporter and he said, um, “This story is about scrutinizing inflexible policies for corporate convenience that results in curtailing the creative process and stifling individual speech that is focused on healing, not harming, and our responsibility to protect the difference.” I don't disagree with that point, but I also don't think it's that complicated. To me, it's about power and deference. So as we have parsed out here, the origin of this word is baked in the origins of this country that we built. This country, which is profoundly and unilaterally racist. I feel like giving black folks exclusive use of that word is a form of reparations.

Walter: And that's fine, you know? I mean, I don't agree with you. And you know, I understand why you're saying it and, and, and really, I even have sympathy for that stance. But I, you know, it's like I'm living in a, in a country, you know, and I can say what I want to say in this country, and everybody else can say what they want to say in this country. If indeed that's done on purpose for conflict, no matter what it is, I think that it needs to be questioned. But if somebody says, “You know that guy came up and he said whatever.” I say, “Okay. He said that. So do you like that?” I say, “Well, no, I don't really like it. I don't like it that they said it.” And that way I don't disagree with you, but I'm going to leave freedom of speech alone. I'm not gonna, I'm not gonna attack it at any point, partially because me attacking free speech is going to bite me on the ass, and I know that. You know, I know that in the end I have to be able to say everybody in this country is free because I'm free, you know? And that, you know, and, and, and in that moment, I'm happy with that. Uh,

Rebecca: How did you respond to the police officer?

Walter: Well, cautiously. It was a police officer. He had a gun. So, you know, I didn't want to get arrested, didn’t want to get beat up. I didn't want to go to jail, you know. I just, he finished saying what he said and I just, okay, okay. You know, 'cause you know, he was, he was insulting me and I knew that. And my response to him could have been many things, but we all know that that's not necessarily gonna work. Me, you know, me going, you know, leaving there and saying, “This is what this officer said.” Well, number one, that would never work because it's my word against his. But number two, it would put me in all kinds of jeopardy. And I understood that at the time, which is why I was telling the story, you know?

Rebecca: So you, the decision to leave your job…

Walter: Yeah.

Rebecca: Did or did not have anything to do with racism?

Walter: Uh, the reason to leave my job had to do with a McCarthy-istic-like institution was trying to control my life, saying either you have free speech or you have the right to pursue happiness, but you cannot have both. And I said, “Man, I'm not dealing with that.” And of course, I'm in a lucky position and for a lot of reasons. I could leave the job. I could, you know. I have money and I can, and I'm going to make other money in other places. I didn't need them. Secondly, to write the op-ed piece, there are a lot of people, like there was a young black woman, you know. A friend of a friend of mine, she was in a writers’ room. She was talking to the head writer, a white woman, and she said to the head writer, the white woman, “Well, you know, as a black woman, I feel…” And the, and the white head writer stopped her, put her hand on her forearm and said, “As an African American woman.”

Rebecca: She did not touch that woman's arm.

Walter: African American woman. She corrected her. I really, honestly, the idea that I'm going to correct you to… as to what you call yourself…

Rebecca: How do you not see that as absolute racism?

Walter: Oh listen. You know, I'm not denying that. It's just you asked me why. You know, like what I'm doing. What I'm thinking about is that this woman can't all of a sudden say to the white woman, “No, I'm a black woman. And you have to respect that.”

Rebecca: She can.

Walter: No, no, no, no.

Rebecca: She should be able to.

Walter: She can. And she should. But if she did, that's the first step toward losing her job, toward losing her future. And she's more worried about paying her rent, paying for her children.

Rebecca: Because racism.

Walter: Well, well, but, but listen, they do it to white people too. I mean, like, I'm just like, there's, there are all kinds of people who get into all kinds of trouble for saying and doing things that become, uh… Like for instance, if you walk in and a woman is wearing a sweater with an elephant on the shoulder and you said, “Wow, that's an elephant on your shoulder.” Depending on where you are, you can get in a lot of trouble for that. I know a friend of mine was, was talking to me about a guy who was a guard at, you know, this big nonprofit. He's walking down the street and one of the people who usually walks in is sitting in a window and he looks at her and he says, “Oh, there you are in the window.” He, he lost two weeks' pay and had to go through reeducation because she interpreted what he said as, “You're putting yourself on sale.” You know, which he didn't say. He said, “You're sitting in the window.” But you know, like if that can happen and happens to so many people in so many ways, for me to try to say, well, it only happens to black people. I know that's not true. You know?

Rebecca: This sounds very both sides to me. This sounds very, you know… That’s what you’re saying.

Walter: Listen, I’m talking about a thing. Like when a person says, “You can't say a word.” I don't care what that word is. That's a problem. That's what I wrote the thing about, and that's what I'm talking about. You know, I belong to a union. There's all kinds of people, men and women, and black people and Asian people and white people. And you know, for a long time there was only white people in it. But that's not true anymore. And you know, it, it still needs a lot of, you know, reparations, when we talk about reparations. But still a lot, you know, I'm, I'm, I was in the two rooms I've been in, have been mostly people of color.

Rebecca: So the takeaway here is that people should be able to say what they want to say.

Walter: People should be able to, people should be able to use language. Now. Again, I'm still saying, I'm not saying that people should harass people or bully people or humiliate people, though those are different kinds of things. If I, if I'm specifically attacking you in like in this conversation then… Well, you know, in this conversation would be okay ‘cause radio. But in, in like if we're at work, that would be a problem and somebody needs to deal with it right. But dealing with it is not having like a Big Brother-like organization calling me up and telling me what happens. They should just say, “Listen, you guys should get together and talk about this. ‘Cause there seems to be a problem.” Like, you know, and even there, it doesn't happen. Again, that's not an issue of race. It's an issue of like there are people like McCarthy who, you know, was against everybody. You know, who, he could get the slightest little hint of socialism. You know, like, I'm saying, “No, you can't do that to me. You can’t do that to my people. And my people are all kinds of people. Certainly there's race and racism involved. Certainly if I was a white person, I could not have written that op-ed piece. But, in a way, I'm speaking for a lot of black people. A lot of black people are getting in touch with me. They're telling me, “Listen, this happened to me. And that happened to me. And I did this. And they did that.” Also, people who are gay, uh, people who like, people who are anything that's kind of outside the norm, you know, of white male America. And I understand that. So there's not, I, I'm not trying to say to you that race, you know, doesn't play an aspect of this. But I'm also saying that there are other parts to it that I'm not, you know, because I have to be willing to say, “Okay, that guy said this. You know, what do you think about that?” And I say, “I can say I don't like what he said, but I don't feel that he was, you know, in any way doing it wrong.” Just like this woman, you know, like at the LAUSD, just saying, “Oh, I'm so happy to see you, boys.” She should've said “young men.” And I'm sure after that she always did. But you know, I don't think that the guy next to me should try to kill her. You know? Especially for him. 'Cause if he killed her, he'd be in prison for the rest of his life. You know? And I think that we need to be able to control and to understand what we say, how we say, but not let anybody else do that to us.

Rebecca: You said earlier that the N-word is worse. You think that the N-word is worse. Talk about that.

Walter: Oh my god. Well, somebody coming up to you saying… ‘Cause the guy called me, he goes, you know. And listen, I don't know if he was a white guy. He sounded like it but he might not have been. Uh, he said to me, he said, “Uh, Mr. Mosley, we hear that you use the N-word.” And I'm like, “The N-word is worse than calling somebody a n-gger, man. You know, the N-word is like… That, that makes it okay for you to say, “N-word, N-word, N-word, N-word.” I mean, it's like, it's not bad. You can say it as much as you want, you know? And the other words, the C-word, you know all the F-words…

Rebecca: Which is why they use it.

Walter: Right. Exactly. And, but listen, a lot of black people use it. A lot of black people say the N-word, and I'm like, “Man... So you just made it accessible, like, cause you know…”

Rebecca: But it's not the same thing. It doesn't have the same…

Walter: It's referring to that word.

Rebecca: Right. Referring to a word is not the same as saying the word.

Walter: But if you use the word, it has power and you might… Like every time, every time I say it, in all of these conversations, I get a little upset. I go, “Oh my god, I just said that.” You know? But I'm saying it because it's important for me to get across the meaning of what I'm saying. If like, for instance, the Times they're saying, well the first time… ‘Cause you know really when I wrote this piece, the title I said is “The n-gger in the room.” Right? They said, “Well, what if we say the N-word in the room?” I said, “No. You can't say that because it's absolutely against what I'm saying. You know?”

Rebecca: So you just said that every time you say the word, it upsets you a little.

Walter: Oh yeah.

Rebecca: Why?

Walter: Because, because of everything that you said before. I don't disagree with you. I understand. There's a whole history of the use of the word, which has been used to oppress me and mine. I get that. You know? And so when I say it, but... What I said in the room, and I said, “I'm telling a story that is my experience in the world. Mine, you know, as Walter Mosley's.” Then I had to use the word in order to get the idea across of how powerful what happened, happened. If I said, the policeman said, “When I see an N-word in a P neighborhood or a P and a N-word neighborhood…” You know, that's like... You know, all of a sudden, it's accessible. It's easy. It doesn't bother anybody. It's fine. But it isn't accessible. It's not easy. It should bother people. And that's why I said it. You know, it should bother you, but just because you get uncomfortable because I say something. Like, you know, we shall be free. That don’t mean nothing. I can still say it. You know, and you send things back to me, depending on, you know, who you are. You know, It could be women saying, it could be, you know, people who are gay or transgender or whatever, you know. Hey listen, I get it. You know? And the more we talk, the closer we become. The less we talk, the more we're isolated from each other.

You just heard me talking with Walter Mosley - his latest book Trouble is What I Do is out now.

Alec Hamilton, Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produced this episode, with editing by Anna Holmes and Jenny Lawton. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the music is by Isaac Jones. Special thanks to Jennifer Sanchez.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - follow me on Twitter at @Rebel19 for all things Come Through.

Until next time.