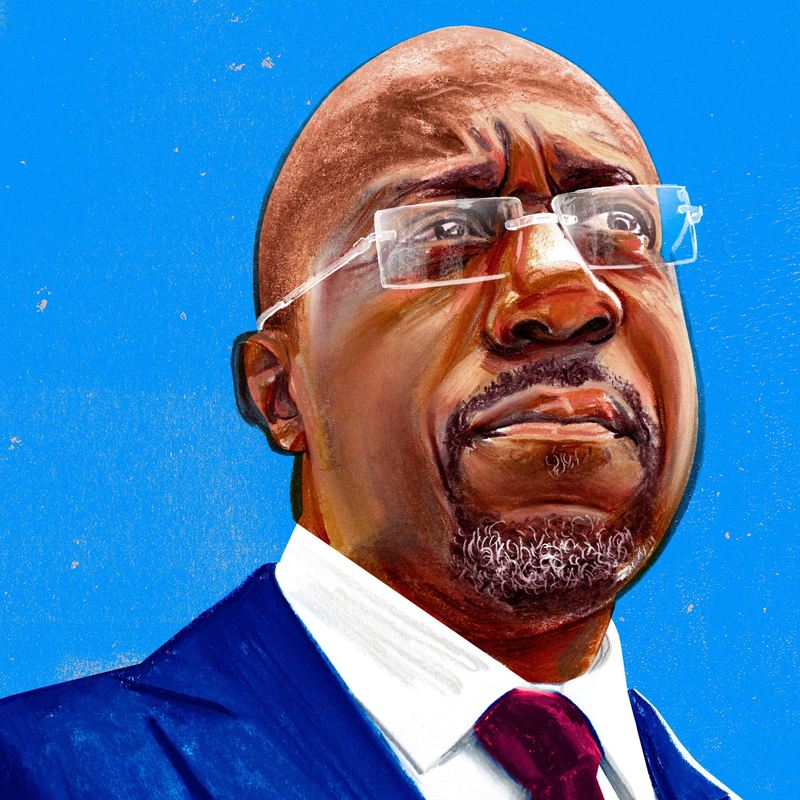

Senator Raphael Warnock on America’s “Moral and Spiritual Battle”

Interviewer: When Raphael Warnock was elected to the Senate from Georgia, he made history a couple of times over. He became the first Black Democrat elected to the Senate from a southern state.

Raphael Warnock: My mother who as a teenager growing up in Waycross, Georgia used to pick somebody else's cotton. The other day, because this is America, the 82-year-old hands that used to pick somebody else's cotton went to the polls, and picked her youngest son to be a United States Senator.

Interviewer: Warnock's victory in that election alongside the young Jon Ossoff, also flipped both of Georgia's senate seats from the GOP to the Democratic Party, a rare feat. Once a Republican stronghold, Georgia has now become a swing state, one that Joe Biden can't afford to lose in November. From what the polls tell us, Biden faces a very uphill battle in Georgia. His support among Black voters, Black men in particular is suffering.

Warnock's ability to inspire voters in Georgia and beyond may be critical to what happens this November. Before going into politics, Raphael Warnock spent his life as a minister, and he remains the senior pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. The same pulpit from which Martin Luther King Jr. once presided.

Martin Luther: Now that you have what you have, and you are who you are, what are you going to do, child, with yourself? Now that everybody knows your name, do you know who you really are?

[music]

Interviewer: Do you prefer Senator or Reverend? [crosstalk]

Raphael Warnock: Senator, Reverend, Reverend, Senator it doesn't matter.

Interviewer: Well, I'll go with Senator.

Raphael Warnock: That's fine.

Interviewer: Because it's Senator, let me begin with a political question of the day. We are in a week following a guilty verdict on 34 felony counts for the former president Donald Trump. Yet his fundraising, if the RNC can be believed is through the roof, $70 million after two days after his conviction, and the polls don't seem to be moving in any significant way. Trump has a base of supporters inspired, inspired by the notion that the criminal justice system is somehow meaningless, just politics.

I think it's possible to imagine that if a presidential candidate 15 years ago had gotten these felony convictions, that person would be out. How do you as a democrat respond to that?

Raphael Warnock: I think that the country has long been in a spiritual crisis certainly exacerbated by the reality of Trumpism in the world. It's something I think about, first of all just as a pastor and as a citizen. I still have a great deal of confidence in the American people because the reality is he only wins by subtraction. That is his only shot, which is why I'm focused on making sure that every eligible American has a chance to exercise their franchise, and to know that their vote will count. This election is not about who he is, it's about who we are as an American people.

Interviewer: Senator, one of the factors that figures into what may or may not happen in November is for Black voters under 50, and this is according to research by Pew. 29% is leaning to Trump. That's a heck of a lot. It's a huge jump from voters 50 and over. Why do you think this is happening?

Raphael Warnock: I pay attention to polls, I'm not obsessed by them. I think there's a long time between now and November. I will hazard this hunch. 29% of Black voters are not going to vote for Donald Trump.

Interviewer: You're just saying-

Raphael Warnock: The polls are the polls.

Interviewer: -the polls are out of their collective minds.

Raphael Warnock: It's not going to happen. Here's the work that we have to do in the days ahead and in the months ahead. We've got to do what I do every Sunday. We got to tell the story. I would be worried quite frankly if we didn't have a good story to tell about the work we've done. The fact is Black wealth is up 60% since before the pandemic. We've seen a 30 year high in the creation of Black businesses. Black unemployment is at a historic low. With my pushing and urging, 5 million people have received student debt relief under Joe Biden to the tune of $164 billion.

Interviewer: Senator with genuine respect, I understand all that. The problem is, is your message getting through, because when you have a situation when 29% of the Black voters under 50 across the nation are leaning to Trump, despite all the evidence that you are correctly marshaling and presenting, there's a problem, there's a deep problem, and it could be a problem that is decisive in November.

Raphael Warnock: Yes. I stand by my assertion, and not as a pundit, but as somebody who knows a little bit about the Black community. 29% of Black folk are not going to vote for Donald Trump.

Interviewer: 29% under 50, but okay yes.

Raphael Warnock: Oh, under 50, under any age. What we've got to do is turn our people out. If our base turns out, and with the same coalition that swept me and Jon Ossoff in the office, if Black voters turn out, Donald Trump loses, period.

Interviewer: When you talk to people in the Biden campaign, and when you talk to President Biden, what do you want to see them do and do better?

Raphael Warnock: When I've seen the president in Georgia, there's been a great deal of excitement around him and also around vice president. There's no question. We have to keep doing that work, and again, I would be worried sick if we hadn't gotten anything done. One other data point for you, Joe Biden has nominated and we have confirmed more Black women to the federal judiciary than all of his predecessors combined.

Interviewer: You are the child of pastors. You spent your life in the pulpit. When you decided to run for the Senate in 2020, you moved to the more earthly realm, the political realm. How were those two jobs the same or different, and what was that decision like for you?

Raphael Warnock: Here's the thing. My faith and my understanding of the gospel, and of the Hebrew prophets, and the ethic of Jesus has meant that my ministry has always been very much grounded in worldly affairs. Jesus had an agenda. He said he came to preach good news to the poor. He singled out the poor, to open the eyes of the blind, to set the captives free. I have long tried to make that come alive in my ministry. That's why more than a decade ago, I was fighting for Medicaid expansion in our state.

I preach every Sunday in memory of one who spent much of his ministry healing the sick. Even those with preexisting conditions. That's what leprosy was, a preexisting condition. He healed them, and he never billed them for his services. If you go back and listen to my sermons long before I even knew I'd be running for office, I was talking about the same things I'm talking about now. In that sense for me, my work in the Senate while not pressing my particular faith tradition on anybody, I represent all the people of Georgia regardless of their faith, tradition, or if they claim no faith at all, but my work is an extension of my ministry.

Interviewer: You must have thought at some level that by shifting your emphasis, shifting your efforts from the pulpit, and I know you retain that, you continue to preach, but by shifting majority of your time to a senator that you could make a greater impact on human beings in Georgia and in the nation. Were you right or were you wrong?

Raphael Warnock: I'm the senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church where Martin Luther King Jr. served alongside his father. I come from a tradition where we believe that once faith ought to come alive in the public square. For me, these roles, pastor who is also senator, senator who returns every Sunday morning to preach in my pulpit, those roles aren't in conflict. They are complimentary. I think having been a pastor before serving as a senator has made me a better senator because there are long stretches of time in this work in the Senate, in politics where you don't get to do exactly what you'd like to do.

You've got a vision for how you want to help people, but change is very slow. By the same token, serving every day at Washington in the Senate has given me a great deal of preaching material. If I never understood sin before, I understand it now. Human pride and arrogance, the obsession with power.

Interviewer: I can only imagine. Just this week I was watching Marjorie Taylor Greene interrogate Anthony Fauci, and it was a spectacle of spectacles. Unfortunately, it's also typical of what you see in the halls of Congress. I wonder how else can I put this, does your life as a senator ever drive you to the brink?

Raphael Warnock: Listen there's a way in which life-

[laughter]

-if we're paying attention-

Interviewer: Say no more.

Raphael Warnock: -life can push us all to the brink from time to time.

Interviewer: When does that happen to you in the Senate?

Raphael Warnock: Look, this is hard work. What can be most challenging is when the solutions really aren't that complicated and you know in your gut that what's stopping us from solving the problem is not the logistics, it's not the lack of resources, is sheer politics. I think this obsession with winning the game is part of the spiritual problem that's afflicting the soul of our country to the degree that, for example, we won't even do what's necessary to save our children from the awful reality that any one of them is a candidate for indiscriminate violence by guns every single day in classrooms all across America. The fact that we would stomach that is why I do feel frustrated some days. I'm inspired by people like Dr. King, like John Lewis, who was a member of my church, by so many others who faced-- They faced challenges where victory was quite improbable, but they kept soldiering on.

Interviewer: Right now there's a big movement of people in this country who say they want to live in a Christian nation with laws instituting Christian principles. By the way, the vast majority of especially people who describe themselves as evangelicals are pro-Trump. What do you make of that? The enormous number of people of earnest faith who look at someone who lies the way he does, who's now been convicted of multiple felonies, how do you analyze that?

Raphael Warnock: There were a number of Christians, a whole lot of Christians who were pro-slavery. There were a whole lot of Christians who were pro-segregation. There's a recurring line by Martin Luther King Jr. in his letter from the Birmingham Jail. He says it a few times in his speeches. He says, "I am so disappointed in the American church." I'm paraphrasing here. I can't channel the eloquence of Dr. King.

He said, "As I travel through the south and I see its massive churches with its massive religious education buildings, and its spires pointing heavenward, I ask myself, what kind of people worship there? Who really is their God?" That's the question for this moment. Who really is their God? Particularly, when we've been told by a lot of folks on the far right for years that their focus is family values. When we've raised issues that people like me think are also central to the gospel, like how you treat the poor, they have narrowed the religious discussion to matters of private morality.

One's conduct around issues of human sexuality, marriage, and the like. Those same people now are lined up behind Donald Trump, a man who has had several marriages, who found himself caught up in the crosshairs of his decision to have an affair with a porn star. These same folks who have raised these issues around family values and private morality are the ones who are speaking as if he is the Messiah of God. I think the question that Dr. King asked all those years ago is especially relevant in this moment. Who really is their God?

Interviewer: When you first won your Senate seat in a special election, that was in 2020, that was a stunning victory for the Democratic Party in Georgia statewide election. The state went for Biden, and both Senate seats flipped from Republican to Democrat. That shocked a lot of people. First of all, how did that happen, and what trends tell you that you can maintain a Democratic hold in the state of Georgia because the numbers so far suggest it's going to be very, very difficult?

Raphael Warnock: The short answer is it happened because some people kept the faith. I got elected on January 5th, and they called the race for me on January 5th. The next day I was doing all these morning shows, but by afternoon we got the other side of that complicated American story of violent assault on the Capitol. That's the moral and spiritual battle we're in right now. It's between January 5th and January 6th. A nation that can send from the south a Black man and a Jewish man to the Senate or are we that nation that rises up in violence as we witness the demographic changes in our country and the struggle for a more inclusive republic. I choose January 5th, and I'm fighting for the soul of our country.

Interviewer: We recently talked with Georgia's Secretary of State, Brad Raffensperger, and there was a lot of talk among Democrats about voter suppression In Georgia. For example, the photo ID laws for absentee voting. In reality, voter turned out for your 2022 races was much higher than a typical midterm election. How would you explain that?

Raphael Warnock: Listen, the fact that people showed up doesn't mean that voter suppression doesn't exist in Georgia.

Interviewer: How do you square those two things?

Raphael Warnock: Even at record voter turnout in Georgia and across our country, it's not where it ought to be. We ought to be making voting easier and not harder. I don't think the onus is on me to explain why it is unnecessary to create barriers and make it harder for people to vote. The onus is on the Secretary of State. The onus is on the Georgia legislature to explain why would you create a provision and a law so that any average citizen can literally challenge the electoral legitimacy of your neighbors and say, "This person's not legitimate." Then they've got to go and respond to someone they don't even know. I think there were like 100,000 such cases filed in one instance. As it turns out, about 89,000 of those 100,000 cases came from six right-wing activists.

Interviewer: One of the fissures in the Democratic party that we're seeing is related to Israel's War in Gaza since the October 7th attack by Hamas. How do you see this changing the party over time, and how will it affect the presidential election?

Raphael Warnock: There's no question that it's a tough issue long, complicated story. Beginning with October 7th, this chapter is heart-wrenching, this attack on Israel, unlike anything we've seen since the Holocaust, not enough people are talking about the use of rape and sexual violence as a weapon of war. Hostages who were taken away, elderly people, babies, brutal inhumane treatment that just shocks the conscience.

It's not to be forgotten. Then we are witnessing the catastrophe that is happening in Gaza, which even before this conflict was an open-air prison, really a pit of human misery. I don't believe that the answer to death and destruction is more death and destruction. I'm on the record saying that I think this incursion into Rafah is a mistake. I don't think it's good for Israel, let alone the Palestinians who were there.

Interviewer: Senator, Benjamin Netanyahu, is going to speak to a joint session of Congress. Bernie Sanders has decided not to attend that because he thinks that Netanyahu is guilty of war crimes. Will you be in attendance, and if so, why?

Raphael Warnock: Israel is our ally regardless of who the Prime Minister is. This is something that I'm thinking about all the time. I will be interested in hearing what the Prime Minister has to say, even as I carry out my responsibility to govern for the sake of our national security for Israel's national security and in a way that centers human dignity and human rights.

Interviewer: Finally, Senator, in April, the Pope invited you to meet with him at the Vatican. Why did he want to meet with you in particular, and I'd love to know about your conversation?

Raphael Warnock: It's one of those things that I'll always remember. I have long admired Pope Francis. He is someone in my estimation who has found a way to always center human dignity. We don't agree on all things, but that's not necessary. I don't always agree with myself on some things. I was interested in this in particular because I'm a person of faith who is engaged in politics. By the way, if you work in a church of any size, Catholic or Baptist, you know about politics, anyway. [laughs] If you ever been to a deacon board, you know about politics. At the end of the meeting, he suggested we pray. In fact, he asked me to pray first. I prayed for him, and he prayed for me. We prayed for our world, the world grounded in justice and where all of God's children in Gaza and in Georgia know the reality of peace.

Interviewer: Senator, do you pray for an election result in November?

Raphael Warnock: I believe that a vote is the prayer for the world we desire for ourselves and for our children. What I'm urging people to do is to pray not only with their lips but to pray with their legs.

Interviewer: Senator Warnock, thank you so much.

Raphael Warnock: Thank you.

[music]

Interviewer: Reverend Raphael Warnock is a US Senator from Georgia and the senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.