Bruce Springsteen Has a Gift He Keeps on Giving

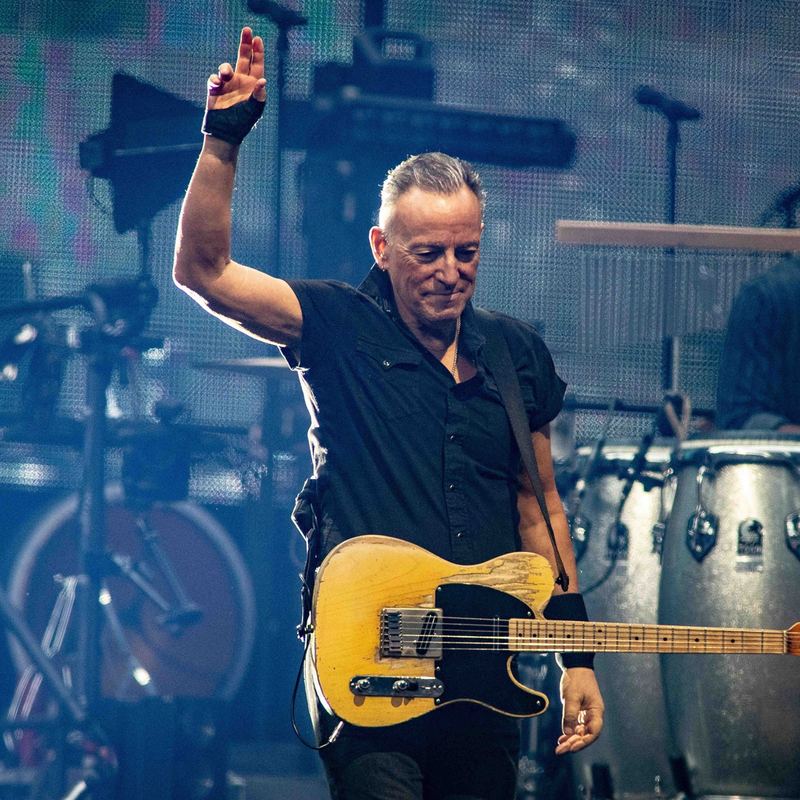

David Remnick: Welcome to The New Yorker Radio Hour, I'm David Remnick. For fans of Bruce Springsteen, and there are a lot of us, this has been a complicated year. Some shows had personnel changes because of COVID and some of the fall tour was canceled in the end as Springsteen recovered from an ulcer, but in 2024, he'll go back out on tour all over the US, Canada, and Europe from the spring through next November. This guy can't be stopped.

Now, I'm not really impartial here. I first set eyes on Bruce Springsteen in June of 1973. I was 14, a boy from North Jersey. I told my parents some kind of lie and I took a bus across the river all by myself to New York City. I had a $4 ticket in my pocket to see a band called Chicago, which was huge at the time if you're old enough to remember, 25 or 64, and all that stuff.

Anyway, I climbed to the highest seat in Madison Square Garden, the old blue seats, and out trundled this opening act, a skinny guitar slinger and songwriter from down the shore. It turns out this guy was outrageous. He was singing, dancing, stabbing at his guitar, leading the band with a crazy urgency, bursting all the while through the indifference of an arena crowd that had not come to see him at all, they had come to see Chicago, but in every sense, he was brilliant. Springsteen hated those gigs at Madison Square Garden as a backup, but they were a breakthrough. His career took off, even as he reentered the realm of smaller arenas.

Now 50 years later, 50 years later, he's racked up more than 20 top 10 albums, a Presidential Medal of Freedom, an Academy Award, a one-man Broadway show, and more Grammys than you can count, as well as a terrific autobiography called Born to Run. Born to Run came out in 2016 and I sat down with Bruce Springsteen to talk at the New Yorker Festival. Let me ask you this, people tend to write their memoirs at different points in their lives. Barack Obama wrote his when he was, I think barely in his 30s. You've waited, you've probably thought about this over the years. Why now?

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: Well, I wanted to do it before I forgot everything.

[laughter]

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: It's getting a little edgy with some of that so this was the time.

David Remnick: Did you do any research? Did you think, "Oh my God, I forgot all about X, Y or Z and I have to go look at the clips, or Jon Landau is going to remind me, or Patti is going to remind me"?

Bruce Springsteen: I had a few friends I called up [unintelligible 00:03:00] was in the Castiles with me. I gave him a call and we threw around some of the Castiles memories. The trickiest part to write about was the third section of the book where it's all people you're living with and people you currently have a life with, and so you're a little more sensitive about that section, and Patti was very helpful with me there.

David Remnick: As a censor or--

Bruce Springsteen: No.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: Not really, she cut me a lot of slack and gave me a lot of room to express myself, so I have to thank her for that.

[applause]

David Remnick: T-Bone Burnett once said that rock-and-roll is one long scream of daddy.

Bruce Springsteen: Wahh. [laughs] I believe that's true. That's true in my case, anyway.

David Remnick: Your father, the reality of your relationship and his difficulties and the anxiety it caused you when you're young and its afterlife, and its profound influence on your work is a dominant part of this book. I wondered if you could read, there's a passage on page, in fact, 29 we discussed before we came in.

Bruce Springsteen: Yes.

David Remnick: Get out those reading glasses.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: Put those cameras down.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: I only use them in bed.

David Remnick: There it is.

Bruce Springsteen: All right. Okay, here we go. Unfortunately, my dad's desire to engage with me always came after the nightly religious ritual of the sacred six-pack. It was one beer after another in the pitch dark of our kitchen. It was always then that he wanted to see me and it was always the same. A few moments of feigned parental concern for my well-being followed by the real deal. The hostility and raw anger toward his son, the only other man in the house. It was a shame. He loved me but he couldn't stand me. He felt we competed for my mother's affections. We did. He also saw in me too much of his real self.

My pop was built like a bull, always in work clothes. He was strong and physically formidable. Toward the end of his life, he fought back from death many times. Inside, however, beyond his rage, he harbored a gentleness, timidity, shyness and a dreamy insecurity. These were all the things that I wore on the outside and reflection of these qualities in his boy repelled him, made him angry, it was soft, he hated soft. Of course, he'd been brought up soft, a mama's boy just like me. One evening at the kitchen table, late in life, when he was not well, he told me a story of being pulled out of a fight he was having in the schoolyard. My grandmother had walked over from her house and dragged him home.

He recounted his humiliation and said, eyes welling, "I was winning, I was winning." He still didn't understand he could not be risked. He was the one remaining living child. My grandmother, confused, could not realize her untempered love was destroying the men she was raising. I told him I understood that we've been raised by the same woman in some of the most formative years of our lives and suffered many of the same humiliations. However, back in the days when our relationship was at its most tempestuous, these things remained mysteries and created a legacy of pain and misunderstanding.

[applause]

David Remnick: I think, Bruce, part of the emotional power of that is that you understand so much of it now, but in real time, as a young person you understood so little. In other words, what's the gulf? How long did it take you to begin to understand him from the inside?

Bruce Springsteen: Let me see, 35, 40, I don't know, 50 years, two psychiatrists, one died on me already.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: A long time.

[laughter]

David Remnick: At the same time, in this book, there's a heroic and lightning presence in your life and in this book that's a counterpoint to your father, and that's your mother. One of the most touching things about it is that she not only by force of will holds this family together, but it's also a musical presence in your life. She's sitting there watching this music that you would have thought was incomprehensible to someone of her generation. She loved it.

Bruce Springsteen: When you think about it, when I was 13, and what was she, 30-- she's only in her early 30s, probably, mid-30s. She was excited by Elvis Presley, and she was interested in The Beatles. We had the radio on top of the refrigerator that played top 40 music every morning when you came downstairs. Music was a big part of her life. We always had the radio on in the car so I heard all the hit records of the day. I think music was passed down in the Italian side of my family. They all played piano a little bit, and of course, there was a lot of singing and carrying on.

David Remnick: You couldn't possibly have thought that this is my way out, the way some kids will think about sports.

Bruce Springsteen: Oh, no. It was just something that obsessed me when I was young and you didn't have any idea where it was going to take you. You looked at the covers of those records and you dreamed and dreamed, but it was a million miles away.

David Remnick: Why was Asbury such a big music scene. It's not such a big place. It's pretty far from New York, but it had an incredibly lively music scene, an outsized lively music scene at that time.

Bruce Springsteen: It was like a Jersey Shore of Fort Lauderdale. It was a place where-

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: -people came to the summer. It was a big season and bands came from all over to fly their wares there in Asbury. It was a center for top 40 bands who came in, played all the little beach clubs and nightclubs and it was just a natural gathering place for musicians. It had a very, very unusual club called the Upstage Club that was open from 8:00 to-- there were no survivors, so whoever is clapping, I don't believe you were there, but it was open from 8:00 to 5:00, which was very unusual. Sold no booze. You could be a kid and get in. The bars closed at 3:00. Those final two hours every musician would line up on the street outside the Upstage to get in and play the music that they really wanted to play in the club after hours. There was an amazing clearinghouse for musicians

David Remnick: When I listened to what surviving records there are in recordings from those early days and read about it, it seems like a million influencers are going on at one time, you had one band that was like Mad Dogs and Englishmen, it was this gigantic band. You had a trio at one point, you're playing--

Bruce Springsteen: I hadn't tried it all. [laughs] It was just different. I was following the times a little bit and I had a nice three-piece band that was fun to play in, where I got to play a lot of guitar and we half-assed Jimi Hendrix and the Cream stuff. I had a big band, 10 piece band, similar to the band we had out on the Wrecking Ball tour where there was a couple of horns and a couple of singers. We played a lot of R&B and all original music. I bounced around in a lot of different genres trying to find something that settled me.

David Remnick: You played teen clubs, you played, I think even trailer parks and you even played the Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital.

[laughter]

David Remnick: If I'm right, you played The Animals' song We Gotta Get out of This Place.

[laughter]

David Remnick: Good set list.

Bruce Springsteen: We just played all over and somehow we got booked at the psychiatric hospital. My main recollection was the guy got up on stage and gave a long introduction of the band, went on, went on, went on. We were waiting to go on, then somebody came up and took him away.

[laughter]

David Remnick: At some point though, you realized I'm a good guitar player, but I'm not Jimi Hendrix, I'm a good singer, but maybe I'm not Roy Orbison, and my way to become an original is to write my own songs. How does that start? How do you have the-- give yourself the permission to sit down and create for yourself?

Bruce Springsteen: We played a lot and we'd been around a lot by that time. I'd traveled across the country a couple of times with the band and we'd seen some other bands and we thought we were pretty good, but I would occasionally bump into somebody who I said, "They got a little bit of an edge on us." I come home and at some point, I was in my early 20s and I just tried to assess my talents one by one. I said, "Well, guitar player," I'm a good guitar player, better than a lot of guys. I'm not the best. Singer. Well, that's a tough one.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: I never thought I had much of a voice. I'm going to have to learn how to sing as best as I can, but I'm never going to make my way just as a singer, plus I'd been writing all along, but I was at a moment where I just came to a crossroads and I said, "Well, if I'm going to take the next step, I'm going to have to write some songs that are fireworks." I'll be able to put across with just the guitar, my voice, and my song because I wasn't working in a band at the time, and I felt I needed to do something that was more original. I just sat down at the piano and I just started to hack out the songs from Greetings from Asbury Park.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Blinded by the Light]

Madman drummers bummers and Indians in the summer with a teenage diplomat

In the dumps with the mumps as the adolescent pumps--

David Remnick: I'm talking with Bruce Springsteen. Bruce realized that if he was going to make it, he'd have to make it as a songwriter. Pretty quickly after that, he had a life-changing encounter with John Hammond, a legendary record producer who had discovered everyone from Billie Holiday to Bob Dylan. We're going to hear exactly how that audition went down in just a moment on The New Yorker Radio Hour. So stick around.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Blinded by the Light]

Some all-hot half-shot was headin' for the hot spot, snappin' his fingers, clappin' his hands

And some fleshpot mascot was tied into a lover's knot with a whatnot in her hand

And now young Scott with a slingshot finally found--

David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick, and this week we're dedicating The New Yorker Radio Hour, all of it, to the favorite son of New Jersey, my home state, Bruce Springsteen. In the late '60s and early '70s, Springsteen was a fixture on the Asbury Park music scene playing night after night after night at bars and roller rinks, Elks clubs, and VFWs with his comrades. People like Stevie Van Zandt. He was schooled in R&B and soul, as well as the songwriting of new people on the scene like Bob Dylan. By 1972, he was looking for a recording contract.

[applause]

David Remnick: Now, at an early point, you managed to get an audition with the great John Hammond, who had discovered any number of jazz greats. Sitting across from John Hammond with just your guitar in an office, he seemed to know right away and that has happened historically any number of times, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Billie Holiday, Count Basie--

Bruce Springsteen: That was a wild, wild day because I didn't have an acoustic guitar, so I had to borrow one from [unintelligible 00:16:12] who was the-

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: -original drummer in the Castiles.

David Remnick: You just made up that name, didn't you?

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: No, there was a baby [unintelligible 00:16:22] and a missus [unintelligible 00:16:23] also, so I borrowed a guitar, I said, "Vinny, lend me the guitar," but it didn't have a case. I have to get on the bus and I got to go to New York with the guitar over my shoulder, which is very embarrassing.

[laughter]

David Remnick: Mythological almost.

Bruce Springsteen: We get to the city and amazingly enough, the music business at that moment was such that John Hammond, one of the greatest A&R men and producers of our time, were seeing idiots off the street.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: That was the lay of the land, amazingly enough. I had two choices. I could say, "Well, okay, this is your moment, Mr. Bigshot, when you're going to see if you've got anything or you don't." I decided not to do that to myself.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: Instead, I tried to do a little mental jujitsu where I said, "Well, I have nothing," so I have nothing to lose. If nothing happens, I'm going to walk out the same as I walked in. I almost convinced myself of it. By the time I got out there, [laughs] I couldn't completely buy my own bullshit, but I tried.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: We went in and there was John Hammond sitting across this very small room, not much bigger than this carpet, little tiny corner room, had the gray suit on, the tie, the gray flat top haircut, the horn-rimmed glasses. We walk in and Mike Appel, my manager, immediately begins to hype me. The next biggest thing since Shakespeare and Bozo the Clown, and tells John Hammond that he brought me to him to see if he really had ears or if discovering Dylan was a fluke.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: Now I'm standing there with my naked guitar having one of the biggest weenie shrinkers of all time.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: Mike is happy that he said his piece and he goes and sits on the windowsill and folds his arms, and John Hammond says, who's ready to hate us by that time, says, "Well, play me something." I sat down and I remember I closed my eyes and I played him Saint in the City.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Saint in the City]

I had skin like leather and the diamond-hard look of a cobra

I was born blue and weathered but I burst just like a supernova

I could walk like Brando right into the sun

Then dance just like a Casanova

With my blackjack and jacket and hair slicked sweet

Silver star studs on my duds like a Harley in heat

When I strut down the street I could feel its heartbeat

And all the women fell and said "Don't that man look pretty"

The cripple on the corner cried out "Nickels for your pity"

Them gasoline boys downtown sure talk gritty

It's so hard to be a saint in the city

Bruce Springsteen: When I was done, I looked up, he had that big smile on his face, said, "You've got to be on Columbia Records."

[applause]

David Remnick: Now, one element we haven't discussed is that the great addition to the musical presence of your playing was of Clarence Clemons-

[applause]

David Remnick: -and this was not just somehow a musical addition to the band, it was a spiritual dimension to it. Shamanistic, that's the word to use in the book.

Bruce Springsteen: A band is a dream. It's a dream that you have. It's a dream that all band members are having. It's a dream of another world, of some other place, a place that feels adventurous. It feels, I suppose, safe, where you feel you're accepted. A real band is a very, very, very, very particular and special thing. The connections you make amongst your band members become near sacred positions as you get older. Clarence was like a dream I had. I'd been looking for years for a saxophonist because I love the great sax solos from great soul records and Dion records and I just wanted to hear that sound.

A real rock and roll saxophonist is hard to come by. You don't want a jazz guy that'll come in and slum with you. You need somebody who just is an R&B player and that was Clarence. Clarence was playing with a band called Little Melvin and the Invaders. They were a local soul band that Garry Tallent happened to be playing bass in. Clarence was a bit mythic in the area before anyone met him with the exception of Garry. Then of course he came into the club we were playing in one night and he wandered to the stage and asked if he could sit in and he got up and the sound that came out of the saxophone was a real force of nature. I get to stand next to Clarence and I hear Clarence's sound before it goes into the microphone.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Jungleland]

Bruce Springsteen: It was just an amazing thing to stand next to and to hear, and then also Clarence's presence was unique. He was just a unique person on the planet. There was just only one of him.

David Remnick: Let's play the beginning of a song that's the title track of the book, if we can call it that.

Bruce Springsteen: Okay.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Born to Run]

In the day we sweat it out on the streets

Of a runaway American dream

At night we ride through the mansions of glory

In suicide machines

Sprung from cages on Highway 9

Chrome wheeled, fuel injected, and steppin' out over the line

Oh, baby this town rips the bones from your back

It's a death trap, it's a suicide rap

We gotta get out while we're young

David Remnick: You've heard of that song. A lot is going on there. You've got Peter Gunn and Duane Eddy and Elvis and Dylan and you and a million things going on all at once.

Bruce Springsteen: Everything I could think of.

[laughter]

David Remnick: Seriously, it is everything you could think of. It's everything you could get in there, isn't it?

Bruce Springsteen: It was. I threw the kitchen sink and everything else at it. I talk about it in the book. I said I wanted to make a record that felt like, "Okay, this is the last record you're ever going to hear, and then the apocalypse, my friend." I wanted to make a sound that would feel like that, it would feel completely cathartic over the top. I was trying to make one of the greatest records I'd ever heard.

David Remnick: You succeeded, God knows.

[applause]

David Remnick: Yet if I remember when the record was finished, rather than release it, you threw it into a swimming pool, because you didn't think it was ready yet.

Bruce Springsteen: I had second thoughts.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: I had second thoughts, but I have second thoughts about everything. The record came down and the album was supposed to be done. I'm not sure if I was ready for it to be done because it would mean people were going to hear it. I wasn't sure I was ready for that. Jimmy Irvine visited me somewhere out on the road in Richmond, Virginia, I think, and we played it. We had to go down to a stereo store in town, because there were only records in those days, and you needed a record player and you didn't carry one on the road. You had to go to the records player store and ask the guy if you could play your album on one of their systems.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: We went in the back and Irvine was walking back and forth, and back and forth and watching me watching me watching me to see what my response was. My response internally was, I just want to get out of here. I don't want to have to listen or think anymore. I think at the end of the day, we came back to the motel and I threw it in the pool [unintelligible 00:26:30] It all worked out later.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: I took it. I think Jon Landau helped me out. He said, "Look." He says, "Sometimes the things that are wrong with something are the same things that make that thing great. That's the way it is in life. That's the way art works." I said, "All right, let's put it out."

David Remnick: Then you take this stuff on the stage and performances in the mid '70s and into the late '70s get more and more developed, longer, as if you are trying to lose yourself on stage. It's really like no other performances that we had seen, anybody had seen until that moment, except maybe from James Brown and soul music. What were you up to there? Why so--

Bruce Springsteen: Losing myself was something I was shooting for. I'd had enough of myself by that time to want to lose myself. I went on stage every night just to do exactly that. Playing is orgastic. It's a moment of both incredible self-realization and self-erasure at the same time. You disappear and blend into all the other people that are out there and into the notes and the chords and the music that you've written you rise up and vanish into it. That was something I was pursuing. I was pursuing intoxication.

Why have people gotten intoxicated since the beginning of time? Why will the war on drugs never be successful? Because people need to lose themselves. We can only stand so much of ourselves. [crosstalk]

David Remnick: On that topic, you didn't lose yourself in drugs. In fact, you had a no drugs rule for yourself and the [unintelligible 00:28:40]

Bruce Springsteen: I was too frightened. It took me so long to find a piece of myself that I could live with that I was very frightened with losing that when it came to other substances. Plus, I lived around a lot of drug takers. I'd seen some of the really worst effects. I had friends that killed themselves and friends that really went and never came back. I was very frightened of it. It wasn't for me.

David Remnick: You would say that the audience part--

Bruce Springsteen: I'd take some now however-

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: -if you have any.

[laughter]

David Remnick: I've got something here. I think I've got 14 beta blockers if you would like [unintelligible 00:29:29]

[laughter]

David Remnick: You once said that the audience, for the audience's part, they come not to learn something, but to be reminded of something when they come to see a performer like you or something that they love deeply.

Bruce Springsteen: Yes. What are you doing? You're getting people in touch with the center of themselves, their lifeforce, the part of them that feels why do people come to a show? You want to be reminded of how it feels to be really alive.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: That's what a great three-minute pop song does. In three minutes, you get the entire picture. You get the possibility of life on Earth, and what that can mean, and what it can do for you and do for others. It's just encapsulated in three minutes of what feels like nothingness, but for some reason, has had the power to inspire and lift up, and just bring you closer to [unintelligible 00:30:40] or whatever you're pursuing.

I always feel that's our job. Our job is we are repair men and we're reminders, you come to our show, and I've always figured I don't get paid necessarily to play this song, or that song or this song. I get paid to be as present as I can conceivably be on every night that I'm out there.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: If I'm there, and I'm alive, then I know you're feeling it too. Initially, music was the first way that I medicated my anxieties. I used it, being a good Catholic boy, of course, as a purification ritual, which we are all taught to do. I would simply go out and play until I just burned up or felt incandescent inside. At the end of the night, that's what momentarily satiated all the jagged little pieces of my puzzle that I had running around inside of me, and really, that hasn't changed over the years. I basically worked till-- I always say exhaustion is my friend, and partly because I realized when I was done working the night, the next day I'd feel incredibly clear and quite free and simply too fucking tired to be depressed.[00:33:58]

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: I mean, you've got to have some energy for you to be depressed, you've got to be able to get out there and search through the weeds for the one thing that's going to bust your ass that particular day. Then you've got to put a lot of energy into that thing. Well, if you're too tired to do that, you're feeling better. You're feeling pretty good.

[MUSIC - Bruce Springsteen: Sandy]

David Remnick: I spoke with Bruce Springsteen at the New Yorker Festival in 2016. In a minute, we'll talk about how Springsteen's troubled relationship with his father fueled some of his very best songs. I'm David Remnick, and this is The New Yorker Radio Hour.

[MUSIC - Bruce Springsteen: Sandy]

Sandy

The fireworks are hailin' over Little Eden tonight

Forcin' a light into all those stony faces

Left stranded on this warm July

Down in the town, the circuit's full of switchblade lovers

So fast, so shiny and so sharp

As the wizards play down on-

[music]

David Remnick: Hi. I'm David Remnick. Three of The New Yorker's critics recently sat down to talk about the year in culture. They declared 2023 to be the year, wait for it, the year of the doll. They're not just talking about Barbie. Staff writers, Alexandra Schwartz, Naomi Fry, and Vinson Cunningham, always have an interesting take on what's happening in the movies and fiction and so much more. You can find that on the podcast of the New Yorker Radio Hour.

Now, our program today was recorded at the New Yorker Festival. Our annual event featuring dozens of performances and interviews. In honor of the holiday, we're spending the entire hour with Bruce Springsteen. I spoke with Springsteen in 2016 when he just published his autobiography Born to Run. In the book, he's incredibly frank about his troubled relationship with his dad and his own struggles with depression. One other thing that you were doing on stage was having a conversation with your father. There's a lot of songs about him. When you asked him which songs he liked the best, he said he liked the songs about him.

Bruce Springsteen: [laughs] Yes.

David Remnick: How did that help to do that, not to a shrink, which came along a little later, but to be on stage, and as a kind of warm-up to a lot of your songs, you would have these spoken stories, some of which reflected almost, if not word for word, but very directly in the memoir, which they seemed absolutely true.

Bruce Springsteen: Well, it was an imperfect way to communicate with somebody who you love and whose love you're seeking, but it was the only thing that I had. I was always trying to sort out what our relationship was about. I think initially, obviously, Steinbeck's East of Eden and I said, "Oh, I get that. I've had some of that," and so I cast us a little bit in that way, and it was a way that I could talk about our relationship. I was never going to have a direct conversation about it because it just wasn't possible. My dad was very ill and wasn't susceptible to doing something like that even on his best days.

I had my music, which is where I went to sort out everything in those days. That was naturally where I went to sort that out and I just started to write about it. It worked out somewhat in the end.

David Remnick: Bruce, how did you become a more politically engaged person? That seemed to happen over time. How did that happen and why?

Bruce Springsteen: Well, we grew up like that. We grew up in the '60s. Politics, it was just in the air, it was part of your cultural experience. We were playing for any Vietnam War benefits when we were 19 or 20. That was a very big part of just growing up at that time. It really came up out of my life experience. It wasn't any eureka moment, or it just came out of living and growing.

David Remnick: There was a piece in The Times and it went through various landscapes in your songs, Youngstown, Badlands, South Dakota, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, which is the scene of The River, Darlington, South Carolina. These are all Trump-voting areas, and white working-class areas have changed dramatically in their political orientation since the days of say, Bobby Kennedy. What do you make of that, and do you feel that you have an acute hold on some of these landscapes as you once might have?

Bruce Springsteen: Well, I think if you look at the history of Youngstown or any of the places you've mentioned, you see that basically, I've written about the last 40 years of deindustrialization and globalization. It hit a lot of people very, very, very hard, and their concerns and their problems, and their issues were never addressed by either party really. There's the sea of people out there who were waiting and hoping and looking for something that's going to bring some meaning back into their lives, so it's not a surprise if someone comes along and says, "You want your jobs back. I'm going to bring them back. You're uncomfortable with the browning of America, I'm going to build a wall to keep all these folks out."

You want to hear these kinds of solutions to your problems, unfortunately, they're fallacious and it's a con job. I completely understand why a voice like that would be appealing.

David Remnick: It seems to me that there was a kind of framing in this book, that if the hero of the first part of the book in some ways was your mother, Adele, there's a heroic presence in the latter part of the book where your wife, Patti-

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: Let's hear it for her. [laughs]

[applause]

David Remnick: -and she is a presence in the band, but you're the singular primary presence in the band, and then you come home where things are not as ecstatic-

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: Oh.

David Remnick: -and she's the boss-

[laughter]

David Remnick: -I gather, but also not to make it too programmatic, but what holds you together that you've had some tough times and tough years, this is not a book that has a fake happy ending where depression is concerned, that this is something that, even if you're carried across a sea of people surfing the crowd and standing ovation after standing ovation, that has no effect whatsoever on the next morning, necessarily.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: If only, in my wildest dreams. You're that person on stage for three hours, most people get-

David Remnick: Four, Bruce. [unintelligible 00:40:29] four.

[laughter]

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: Patti's got to live with me the other 20 hours of the day. Most people see the best of me, and she unfortunately bumps into the worst of me, hopefully not that regularly, but sometimes. We connected right from the very, very beginning. Patti came down to New Jersey in 1974, before the Born to Run tour. She came in and auditioned. We were going to take a singer out at the time, which we didn't end up doing.

We sat at the piano together, and she played me some of her songs. This was when I was 24 years old, and she was probably 20. Then we saw each other regularly after that, and I always kid Patti. I say, "Yes, we get along because before you were you, you were me." She was a musician, she was independent, she was very--

David Remnick: Be careful.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: She was just very single-minded, pursuit of her work, and we just had a lot in common which has sustained us for a long time. Needless to say that when I've had my rough times, she's been there and continues to be there at 110%.

[applause]

David Remnick: Bruce, you have three kids who are grown. I have to think that no matter how great a father and mother, it's got to be a little weird on college visiting day, or you're driving down this avenue or that, and people are screaming Bruce. How do you keep that at bay for your children? At one point you describe in the book.

Bruce Springsteen: It's not as hard as people think. A lot of it is how you think about it. Basically, we just go about our business. If something a little strange starts to happen, you can move away from it, or you calm it down. It comes up once in a while, but we've been pretty lucky.

David Remnick: Didn't you tell your kids that you're like Barney, the purple dinosaur?

Bruce Springsteen: That was when they were little. They were wondering-

David Remnick: It didn't work when they were in their 20s.

[laughter]

Bruce Springsteen: -why do people want you to scribble your name, pre-selfie, why do people want you to scribble your name on a piece of paper? They were just puzzled by people approaching us, and I said, "Well." I had to explain it to them. I said, "Okay, Barney, the dinosaur. Are you interested in Barney?" He said, "Yes." "People are interested in me in the same way, except grown-up people." That actually--

[laughter]

David Remnick: That worked?

Bruce Springsteen: It actually made a lot of sense to them. They were pretty divorced from it. I think one day, Evan came home and said, "Dad, what's Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out?"

[laughter]

David Remnick: I said, "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out? Where'd you hear that?" "I heard it at school. Somebody said their parents are always singing Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out." I said, "I don't know. I'll show you what it is." I got the guitar and I started to play a tune Barney style. He said, "No, Dad, no, dad, play it for real." I played him the song. I said, "That's it. That's Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out," and it seemed to satisfy them.

There was a moment when the children were actually saying, "Okay, we're old enough now to where we need to be a little bit of a part of what you're doing and we need to understand that." Patti was really good at saying-- Because at the time I was so overprotective of the children that I would just basically hide them. She said, "Look, they're going to grow up wondering, why were we being hidden all the time?"

[laughter]

David Remnick: In the attic.

Bruce Springsteen: She said, "Yes, they may get their picture taken, but it's more important for them to feel that we stand as one, as a family." From then on, we went about our business and I think the kids felt better if you took their hand and whatever, walked to your car or your van, even if somebody took a picture, they felt better that you were claiming them. They knew they were an intimate part of even that part of your life.

David Remnick: One of the great stupid questions I've ever asked in an interview, and there are many, as I said to you some years ago, you jump off the piano and you run up and down the ramps and you crowd surf and there's probably going to come a time, probably, not necessarily definitely, that you might find that when you wake up in the morning, as I do, you feel like you've been beaten by a baseball bat and all I do is pick cartoons for a living and I don't do that.

I said, "What are you going to do when that happens?" You said, "Well, I won't do that anymore," which was a stupid question. Can you see yourself becoming, years and years from now, like an old blues man sitting in a chair doing your songs instead of jumping around like a maniac?

Bruce Springsteen: Part of it is you have to not mind feeling like you've been beaten up with a baseball.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: Pain has to become your friend. I don't know. As I say in the book, I forget I have a piece where I say, "The day may come when, and when this happens and when that happens, but not tonight and not right now."

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: That's the way I approach it. I also will have no problem whatsoever sitting in a nice little chair with my acoustic guitar knocking out the songs from [unintelligible 00:46:57] something.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: There is no end in sight so far.

[applause]

Bruce Springsteen: Bruce Springsteen, thank you.

David Remnick: Thanks.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Wrecking Ball]

I was raised outta steel

Here in the swamps of Jersey

Some misty years ago

Through the mud and the beer

The blood and the cheers

I've seen champions come and go

So if you've got the guts mister

David Remnick: Bruce Springsteen is the author of the autobiography Born to Run, along with more than 20 top-10 albums. His most recent is a cover album of Soul and R&B songs called Only the Strong Survive. I'm David Remnick. Thank you for joining us. If you're celebrating this week, I hope you have a wonderful holiday and all the best for the year to come.

Speaker 4: The New Yorker Radio Hour is a co-production of WNYC Studios and The New Yorker. Our theme music was composed and performed by Merrill Garbus of Tune-Yards. This episode was produced by Max Balton, Adam Howard, KalaLea, David Krasnow, Jeffrey Masters, and Louis Mitchell, with guidance from Emily Botein and assistance from Michael May, David Gable, and Alejandra [unintelligible 00:48:17]

Speaker 5: Special thanks and best wishes to a few of our indispensable colleagues, Alex Barish, Julia Rothschild, Monica Racic, Maggie Sheldon, Chris Kim, Alicia Allen, Mike Barry, Ben Richardson, Bruce Diones, and Fergus McIntosh, along with the entire heroic team of fact-checkers at The New Yorker. Victor Guan is our art director, and Golden Cosmos created some of the illustrations for our website.

Misha Lowry provides legal review, David Sakowski, Rob Christiansen, and the engineering team keep us up and running. Julie Cohen does our final air check, Miriam Barnard does basically everything, and the senior vice president of WNYC Studios is Kenya Young. Now, for contributing so much to the show this year, thank you and farewell to Breda Green and [unintelligible 00:49:04]. The New Yorker Radio Hour is supported in part by the Charina Endowment Fund.

[MUSIC- Bruce Springsteen: Wrecking Ball]

Yeah, we know that come tomorrow

None of this will be here

So hold tight to your anger

Hold tight to your anger

Hold tight to your anger

And don't fall to your fears

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.