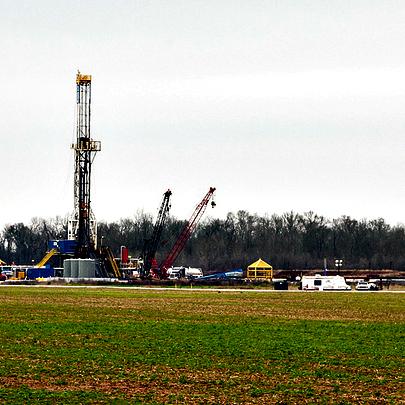

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Fracking, as you probably know, is a controversial method of energy extraction involving pumping tons of water, chemicals and sand deep into the earth at extreme pressures to release oil or gas from shale rock. The practice makes news on an almost daily basis. Take this week. In Illinois, Governor Pat Quinn signed into law what he says are the strictest state regulations for fracking to date. But in Wyoming, the US Environmental Protection Agency abandoned a planned study of fracking’s impact on groundwater. Also this week, the EPA announced that a comprehensive report on fracking’s threat to groundwater and air, commissioned by Congress in 2010, would be delayed until 2016. And next month will see the HBO debut of the film Gasland II. The fracking debate took on considerable steam in 2010, when the first Gasland came out, showing Americans who live near extraction sites, alongside dying animals, sick children and flammable tap water.

[GASLAND CLIP]:

GASLAND: Whoa, Jesus Christ!

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The oil industry was quick to respond.

OIL INDUSTRY SPOKESMAN: All energy development comes with some risk, but proven technologies allow natural gas producers to supply affordable cleaner energy, while protecting our environment.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Abrahm Lustgarten, energy and climate reporter for ProPublica, says that the oil industry and environmentalists are battling hard for control of the fracking story.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: It’s a full-scale war. When I first began reporting on this, the industry was caught off guard. The response to that has been to develop a very sophisticated public relations campaign. You see this in extensive sponsorship for NPR, for example, full-page ads in newspapers for the natural gas industry. A whole host of nongovernmental organizations or lobbying groups that didn't even exist before: America's Natural Gas Alliance, Energy and Depth, the Clean Skies Foundation. And none of these places had even set up offices in 2008.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: And you have gas industry representatives trolling on websites, contributing to chat threads, you know, aggressively engaging in public hearings. Their basic assertion is there isn't hardcore scientific proof that processes associated with drilling are environmentally harmful.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What about the optics of this? There is nothing more arresting then flammable water.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: [LAUGHS] I think you've touched on exactly why that image has become so potent. And most of what we’re talking about is stuff that happens thousands of feet underground, risks that might not be manifested for 10 years or 50 years or 100 years. And that presents a unique set of challenges for the media and for communicating about risk, in general. I mean, “water contamination” is a phrase that no one wants to hear. Water blowing up is something that everybody universally knows is just not supposed to happen.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Tell me about the work that you've done in this area.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: I’d been reporting on the oil industry for the better part of a decade, and in 2008 was told by a couple of geologists that I was interviewing that there was this process called hydraulic fracturing that was increasingly being used in drilling fields. We went to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, where they were considering permitting drilling in the Marcellus Shale and found that the environmental regulators weren’t familiar with this process. They didn't know what the chemicals would be that were pumped underground. And they didn't really have a plan for treating the waste that would be produced as a result.

Those huge gaps in their response really fueled what became a four-year investigation for us, more than 100 stories, probably 15 or so major investigations.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ever since George W. Bush signed into law the Energy Policy Act of 2005 or, as its critics call it “the Halliburton loophole,” natural gas companies don't have to disclose, apparently, a single chemical that's injected into the ground? How can you do quality reporting on fracking, if you have a legal barrier to reporting that?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, that's a very good question. It's actually a bigger question for the scientific community than the journalistic community, in that researchers, you know, water quality experts say that they can’t go out and test for contamination if they don't know what they’re testing for.

Where the media comes in, in this equation is the industry responded to criticism by creating a voluntary disclosure system called FracFocus, and it’s a website that's contributed to by drilling companies in the places that they drill. The media has latched onto that, repeating the industry's assertion that now there is disclosure and well, that problem has been taken care of. Now, we’re starting to finally hear some reports that that disclosure is not necessarily listing the most dangerous chemicals used and is still protecting them behind this veil of competitive trade secrets.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What do you think reporters most frequently get wrong when talking about fracking?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Wrapping this entire issue under the phrase “fracking,” as if fracking alone describes the entire drilling process. You know, fracking is just a couple of minutes in the lifetime of a well. In my reporting, I found that the environmental problems from drilling relate to the disposal of waste, the drilling of the well, the preparation, the construction of that well and then this process itself of, of fracking.

You know, there’s also a lot of false distinctions. We see the phrases now “shale fracking” or “horizontal drilling” batted around that I think present a false distinction between, you know, the kind of drilling that’s happening say in Pennsylvania and the kind of drilling that's happened for decades in Colorado. This is something the oil and gas industry has pushed to present the viewpoint that some of the problems that the country has seen out West might not recur back East. And, again, it’s a reporter’s responsibility, I think, to get beyond those sorts of distinctions.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I wonder whether many of these reports about fracking suffer from the same conflict of interest problem as in the early days of reporting about global warming? In fact, some have termed this problem “frackademia.”

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: There's consistently been serious conflicts of interest raised about some of the most prominent, quote, unquote, “scientific reports.” A couple of recent examples include a University of Texas professor, a former director of the US Geological Survey, who essentially wrote a report saying drilling wasn't a serious environmental threat. And it turns out that he was receiving compensation and had board affiliations with a natural gas company. The MIT Energy Initiative, which is funded by BP, produced a report hailing the benefits of natural gas. Ernie Moniz, who is affiliated with that program, was recently appointed to the Department of Energy.

The technical expertise, it's always laid within the drilling industry. I mean, they employ the petroleum geologists who understand the practice best. From the start, there's been, you know, a dearth of scientific evidence, but the drilling industry is using the tiniest little sliver of scientific uncertainty to drive a wedge between, you know, what might seem like a logical question of risk and any sort of certainty or real answers.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So until there's proof, the environmentalists are going to be on the losing side of this issue, even though they have flammable water.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: What we see is relatively little action from the federal government, and we have a, a study undertaken by the EPA years ago, which is, is far from complete. And, in the meantime, the rate of drilling has increased. When I began reporting on it, it was just in a handful of states. And it’s happening in places like Michigan now and Illinois and North Carolina, that we hadn't really thought of as oil or gas- producing regions. There’s, obviously, a phenomenal amount of activism against fracking, but it hasn't led to any sort of conclusions or answers.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You seem to know as much as anybody, and I just want to know whether you would be comfortable living with this.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: I take a kind of pragmatic view. I don't think that we’re not going to pursue these resources. I think that it's going to happen. And so, the question is how can you do it most efficiently and most safely and make the wisest decisions about the places where drilling is pursued and perhaps the places where it's forbidden.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Abrahm, thank you very much.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Thank you for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Abrahm Lustgarten reports on water, energy and climate change for ProPublica.