BROOKE GLADSTONE: Back in the early days of radio, the nation's biggest singing stars came from vaudeville, where volume was prized and emotion was delivered with a jackhammer.

[CLIP/SWANEE]:

AL JOLSON/SINGING:

I’ve been away from you a long time

I never thought I’d miss you so

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And then Rudy Vallée came along, the first crooner.

RUDY VALLÉE/SINGING:

Waitin' this mornin’

I come knockin’ at your door.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

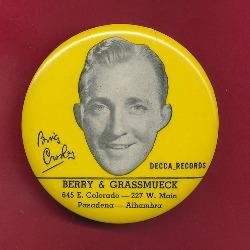

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Managing to achieve something like intimacy, even when singing through his famous megaphone, he was, in fact, a megastar. But the nation’s most enduring, its biggest and best crooner was definitely Bing. I don’t even need to say his last name.

BING CROSBY/SINGING:

Every kiss, every hug

Seems to act just like a drug

You’re getting to be a habit with me.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, Crosby. Paul Ford wrote on the New Yorker website that Bing Crosby helped change American popular singing, change the way radio was produced, and was even responsible, in part, for the birth of Silicon Valley. And then there’s that connection to the Nazis. It’s, it’s not bad, don't worry. Paul, let’s dive into this winding tale. The story starts with just a vaudeville stage. Actually, Bing did start out in vaudeville, right?

PAUL FORD: That’s right. He comes out of well, not exactly vaudeville but on the stage. He comes out of Spokane, Washington and he’s singing with a megaphone and lands in Paul Whiteman's jazz orchestra, one of the places where jazz sort of starts to form in American culture.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Actually, we have a recording of him with Paul Whiteman's orchestra.

[RECORDING/BING SINGING]

Now, back in those days, even when making a recording they didn't have mics?

PAUL FORD: Not always, no. They would actually sort of yell into a horn in the wall. It would write on the wax cylinder, and that’s how you get that kind of [MAKES SOUNDS] KKRRR - you know, sort of scratchy sound. I don’t think there was any electricity actually involved there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So then the microphone seemed to change everything, especially for Bing.

PAUL FORD: Well, he had this sort of beautiful baritone voice, and it – it wouldn’t hit the rafters in the same way as somebody like Jolson’s voice might.

[BING SINGING/UP & UNDER]

But for Bing, he could get up close to that microphone and it sounded like he was in your ear.

[BING SINGING]

It was very central, very intimate. And it just took off.

[BING SINGING]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That sort of crooning created, you say, a moral panic.

PAUL FORD: That's right, people were very, very upset at this change in style. And they – they thought that the crooning represented pretty much the end of morals, as we know it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] You quoted Cardinal William Henry O'Connell saying, “Crooning is a degenerate form of singing. No true American would practice this base art.”

PAUL FORD: That’s right. And the New York Singing Teachers’ Association chimed in, and they say, “Crooning corrupts the minds and ideals of the younger generation.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why?

PAUL FORD: You know, these youth show up. They’re all sexual and they’re singing intimately into the ears of America's maidens.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And all of a sudden, it’s like Time Magazine writing about the Millennials.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] So you think it was just a function of the fact that these were young people? But there was something unique and something that couldn't have been done before the development of microphone technology on such a wide scale.

PAUL FORD: But it's always that combination. The thing that people talk about when they talk about the Millennials is that they’re all on their – you know, they’re text messaging all the time or they’re all on Facebook.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

PAUL FORD: It's, it’s youth plus technology equals just tremendous disgruntlement.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Okay, so then Crosby becomes a huge star in the thirties and the forties. And in the mid-forties World War II ends, and America starts picking through the remains of Nazi technology, and they find magnetic tape, which the Nazis had been using to send out propaganda.

PAUL FORD: That’s right. Now, to be clear, magnetic tape shows up in Germany in, in the late twenties. It’s not purely a Nazi invention.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

PAUL FORD: But it definitely was used by Hitler and, and the regime to broadcast all throughout the Reich.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The Allies didn’t use it?

PAUL FORD: They didn’t have it. It just wasn’t a technology that had made its way to the United States. If you were recording a radio show, for instance, you used a great big wax platter.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What was so good about magnetic tape?

PAUL FORD: You can cut it. You can paste it back together. You can splice it. You can record over it. You can do multi-tracks. It changed audio entirely. It used to be so linear, and now it’s this medium that you can manipulate and you can play around with time in ways that you never could before, which means that you can make mistakes and fix them.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Crosby immediately saw the value of it, right?

PAUL FORD: Somehow, people knew to bring this technology to him. One of the deals he made when he set up his “Philco Radio Hour” was that he would be able to – at that point it was called transcription - transcribe it onto the disk and then it would be played back. It also meant you didn’t have to do multiple shows for multiple time zones. So he was primed. This was something that was totally on his radar. People knew that and said, hey, you might want to take a look at this tape recording. And he said, this is great. What do you got for me? And they said, well, we don’t really have any machines.

So he funded a small company called Ampex. I think it was about six people at the time. He give them around 50 grand. And he said, go, make me some tape recorders.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I worked with Ampex decks when I was, you know, editing in radio - as recently as a dozen years ago.

PAUL FORD: Well, and that’s the thing. Ampex was, was a real fundamental technology company in American history, and especially in Silicon Valley. The Ampex sign is sort of still up there. And tape recording – it not only was a way to record sound, it became one of the first ways to record data off of computers.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And it was his 50,000-dollar investment that started that ball rolling?

PAUL FORD: That was the origin. I mean, it’s definitely the origin of tape recording in America, that sort of came along. People saw that it worked for audio and realized it could work for data, as well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So, how did Bing use it back when he was producing his “Radio Hour”?

PAUL FORD: His show was known for being paced a little bit differently because they had more control. Things are edited and manipulated, and that there’s some play in how they’re constructed. So it was tape recorded in the modern sense. His was the first show to do that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And [LAUGHS] you say that he invented the laugh track.

PAUL FORD: It was either he or a producer. They wanted a, a stronger laugh, and they said, go back and get that old laugh.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And that was that. That’s how it started.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, in your piece, you talk about one of the guys who developed the first hard drive.

PAUL FORD: Right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And he spoke about the Crosby connection in his book.

PAUL FORD: As IBM was funding the creation of the first hard drive, they’re looking at at all these different technologies. There was magnetic core memory. There, of course, were things like paper tape and punch cards. And there were the magnetic tapes, like the kinds made by Ampex. And the hard drive was a specific reaction to all of these technologies that came before. But itself, it’s also another magnetic technology. And so, the history of the magnetic tape, there’s a direct link between all of the hard drives in the computers today, back to those original tapes that came over from Germany.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: He also recognized another technology.

PAUL FORD: Fun fact: There is a patent with his name on it for a kind of window sash, but –

[BROOKE LAUGHING]

- I think what you're talking about is that he was an early investor in flash freezing. And thus, he ended up with a very, very big role in the development of Minute Maid. He became known, really became associated with orange juice.

[AD CLIP]:

WOMAN: Bing Crosby loves Minute Maid.

CROSBY/SINGING: Here’s wonderful news for you and me, that Minute Maid gives more vitamin C.

[SOUNDTRACK UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There is a kind of funny connection between freezing - flash freezing and capturing things on tape.

PAUL FORD: You’re grabbing them for future use. In one case, you’re going to cut and paste something into a more interesting radio show. In the other case, you’re going to have a delicious glass of orange juice.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Manipulated.

PAUL FORD: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS]

PAUL FORD: Mm-hmm, but, but even better.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Paul, thank you so much.

PAUL FORD: Thank you so much for having me.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Paul Ford is a writer and computer programmer. His piece about Bing Crosby ran on the New Yorker’s Elements blog last week.

[CLIP/”DON’T BE THAT WAY”]:

BING CROSBY, SINGING: Don’t cry, oh honey, please don’t be that way.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Here’s my favorite Bing Crosby song. We used to have a gramophone when my kids were small, and I played this song over and over again.

BING CROSBY/SINGING:

And the rain will bring the violets of May,

Tears are in vain, so honey please don't be that way…

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That's it for this week show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Alex Goldman, PJ Vogt, Sarah Abdurrahman and Chris Neary. We had more help from Olivia Weitz and Molly Buckley. And it was edited – by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Andrew Dunne.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our Senior Producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for News, and our boss. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.