A Journalistic Civil War Odyssey

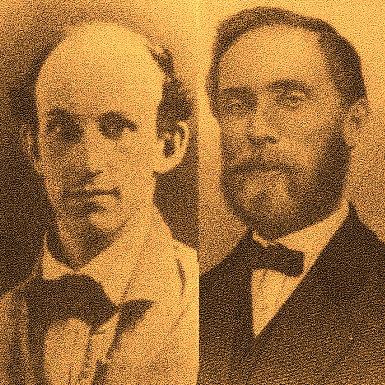

BOB GARFIELD: We’ll stay in the past with a look at Civil War coverage, with a focus on the double-edged sword of embedding journalists with military units on the ground. One-hundred and fifty years ago, two journalists headed with union troops to chronicle the attack on the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi. It turned out to be just the beginning of a long and perilous odyssey. Junius Browne and Albert Richardson correspondents for Horace Greeley’s feisty New York Tribune, didn’t practice journalism quite as it’s done today, but they did risk life, limb and liberty in the Deep South to dispatch news of the Civil War to the North. Peter Carlson, author of Junius and Albert's Adventures in the Confederacy, says the reporters were odd bedfellows but a formidable team.

PETER CARLSON: Albert Richardson was a strong, stocky guy from a farm in Massachusetts. He could go anywhere, talk to all the important people and get the story. Junius was the scrawny, prematurely bald kid with jug ears who had grown up in a rich family in Cincinnati. He read philosophy for fun. He was not a particularly good reporter; he was too shy. His modus operandi was to stand in the background and then write an ironic piece with a lot of literary references.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, let's listen to an example of Junius Brown’s purple prose, one of his dispatches from the Battle of Fort Donelson, the Union's first big victory in the war.

READER/JUNIUS BROWN: Ever and anon a loud cheer went up for the Union, and this was caught up at a distance and echoed by our soldiers and re-echoed by the surrounding hills. Many a brave warrior heard that glorious shout, as his senses reeled in death and his spirit went forth embalmed with the assurance that he had not fallen in vain.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, there’s [LAUGHS] a footnote, Peter, to this story. Junius, the scrawny little aesthete –

[CARLSON LAUGHS]

- apparently played a part in the victory.

PETER CARLSON: Yes, Junius was with a group of snipers at the Battle of Fort Donelson, and they were trying to pick off the guys in a Confederate artillery battery, and the Union snipers kept failing to shoot them. So one of the snipers handed Junius a rifle and said, can you shoot? So Junius aims, and when the Confederate pops up he fires the rifle and bingo, the Confederate battery stops firing. So the sniper says, I think you fixed him that time. I wouldn't be surprised, Brown replied-

[BOB LAUGHS]

- although, of course, he was completely surprised. He didn’t know how to shoot!

BOB GARFIELD: I’m just trying to imagine a contemporary reporter using a weapon, while embedded with troops.

PETER CARLSON: There were no journalistic ethics in those days.

BOB GARFIELD: Later, Brown filed a story invented out of whole cloth or at least stitched from little patches.

PETER CARLSON: Yes, he did. Junius and a reporter from The World, Richard Colburn, were in St. Louis when they learned that the Union army in Missouri had headed south to invade Arkansas. They were about 200 miles away when they began to get little telegraphed reports that there had been a battle, the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas. And that it was very bloody and that the Union had won.

They also knew that Thomas Knox, of the rival New York Herald, was actually at the battle and would no doubt be scooping them. So from their hotel room in Rolla, 200 miles away, Junius wrote a long purple story about the battle, as if he had seen it too.

JUNIUS BROWN: Bayonet, musket, sword and cannon all did their bloody work, and the earth was stained and slippery with human gore. Every loyal soldier kept his eye fixed on his fearless leader. Wherever they saw his streaming hair and flashing sword, they knew all was safe.

BOB GARFIELD: And, of course, they were discovered and fired.

PETER CARLSON: No, they were discovered and everyone in the business was highly amused. Before they were discovered, Horace Greeley wrote an editorial saying how great the story was and that it should be reproduced and given to all Union soldiers. And later, the Times of London reported that it was the best story of the war. [LAUGHS] The press, in those days, made no bones about objectivity. Greeley was a mover and shaker in the Republican Party and he had been a backer of Lincoln; he helped Lincoln get the nomination for President in 1860.

BOB GARFIELD: Well, this kind of advocacy would figure into the travails of Richardson and Brown. So let's get to the heart of their adventure. It began as they were embedded with Union troops on a barge on the Mississippi.

PETER CARLSON: General Grant was going to attack Vicksburg, and if the Union took Vicksburg they would cut the Confederacy in half. So Richardson and Brown were eager to get to Grant’s army. So they got on this barge, which was bringing hay to Grant’s horses and they had to sail past Vicksburg. And the Rebels just fired all their cannons from Vicksburg, blew it up, and Junius and Albert and those Union soldiers were still alive jumped into the water and floated on hay bales heading south. The Confederates sent out a boat and captured Junius and Albert and their friend Colburn, from the New York World.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, as noncombatants, they expected to be quickly released. And the Confederate bureaucracy actually gave them parole papers, which entitled them to be exchanged quickly for noncombatants being held by the Union troops. It didn't work out that way.

PETER CARLSON: No, it didn't. When they got to Richmond they were put in Libby Prison and then all the soldiers who were captured with them and Colburn were paroled but Junius and Albert were not. When Union bureaucracy wrote to the Confederates in charge of prisoner exchange, Robert Ould, the Confederate agent of exchange, wrote back and basically said, we hate The Tribune and we’re not releasing these guys.

READER/ROBERT OULD: It seems to me that if any exceptions be made as to noncombatants. it should be against such men as the Tribune correspondents ,who have had more share even than your soldier in bringing rape and pillage and desolation to our homes. You ask why I will not release them. ‘Tis because they are the worst and most obnoxious of all noncombatants.

PETER CARLSON: For the next 20 months, the Union kept trying to trade Confederate reporters for Brown and Richardson and Ould kept refusing.

BOB GARFIELD: You discovered in the letters that they were writing back North a great deal of celebration about General Grant's victory at Vicksburg. That struck you as odd because?

PETER CARLSON: Because they didn't mention the victory of the Union at Gettysburg, which had taken place a day earlier and hundreds of miles closer. You would think they would have been celebrating that one too.

BOB GARFIELD: But why weren't they?

PETER CARLSON: Well, they were reading the Richmond newspapers, and the Richmond newspapers were informing their readers that the Confederates had won a great victory at Gettysburg.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

READER: Our army victorious at Gettysburg, the Yankee army retreating. The whole breed are as nervously fearful of gunpowder and bloodshed as women and Negroes!

PETER CARLSON: They even ran Union newspaper accounts of the victory at Gettysburg and then they would announce at the bottom that everyone knows this is a pack of Yankee lies.

BOB GARFIELD: Junius and Albert were in one prison and then transferred to another, and then finally they were moved to a prison called Salisbury.

PETER CARLSON: And when Junius and Albert got there in February of 1864, they were thrilled because they had been kept in these stiflingly hot tobacco warehouses in Richmond. Now they were in Salisbury, which had a beautifully grassed yard with stately trees. In fact, they played baseball on good days. At that point, there were only a few hundred prisoners there.

BOB GARFIELD: In the beginning, it was kind of like the scene in Goodfellows, where Paulie and the gang were in prison making [LAUGHS] gourmet dinners and smokin’ cigars. What happened?

PETER CARLSON: In the fall of 1864, the Confederates were besieged in Richmond and they sent most of the prisoners there South, some of them to the now infamous Andersonville in Georgia and others to Salisbury. So instead of having a few hundred prisoners, all of them housed indoors, you now had over 9,000 prisoners living in holes in the ground or crude makeshift tents. And it rained and it snowed and guys were starving. The Union army had deliberately destroyed the bread baskets of Virginia, so there [LAUGHS] was no food to feed the prisoners.

BOB GARFIELD: Junius Brown wrote about that in one of his letters to his managing editor Sydney Gay.

READER AS JUNIUS BROWN: About a thousand have died and mortality is on the increase. At the present rate of death, next August will find none of us alive, but then we will be free. Dante, with all his gloom and horror of his inferno, did not dream of that.

PETER CARLSON: Junius and Albert volunteered to help in the so-called “hospitals,” which were basically just spaces indoors where very sick men would lie on the floor with some hay around them. Albert was made the clerk of the hospital, so he kept records of all the sick men and whether they died or not. Junius went out into the yard with the few medicines that they had and would crawl into the holes they were living in and give them some medicine and try to cheer them up.

At one point, someone asked him what kind of physician he was, and he said he was an amateur physician. Many of the soldiers had no idea what that meant and thought that was some kind of higher degree of doctor because he seemed to be better than the ones inside.

BOB GARFIELD: At this stage your book pivots. The privileges conferred upon them as volunteers in the hospital enabled them [LAUGHS] to just stroll outside of the prison and commence a 300-mile odyssey to freedom.

PETER CARLSON: Yes. They knew that the closest Union army was in Knoxville, Tennessee, and they escaped on December 18th. It was very cold and they had to cross the Blue Ridge and then the Appalachians. In the flatlands near Salisbury, they knew that they could ask the slaves to hide and feed them. In the mountains though there were very few slaves. It was mostly small farms. So they had to rely on a secret organization called the Heroes of America, a pro-Union secret organization with secret signals and handshakes. Those people would lead them from one safe place to another.

BOB GARFIELD: So over the course of about a month they traversed snowy mountain ranges and at last found their way to Knoxville and the US Army.

PETER CARLSON: Albert's cold, he’s wet, he’s half-starved but he has the presence of mind to send back a telegram. All it said was, “Knoxville, Tennessee.”

[PLAINTIFF MELODY, UP & UNDER]

READER, AS ALBERT D. RICHARDSON: Knoxville, Tennessee, January 13th, 1865. “Out of the jaws of death, out of the mouth of hell.” Albert D. Richardson.

PETER CARLSON: And it’s a quote from a very famous and very popular Tennyson poem. So Greeley receives this, publicizes it and they return to New York and write up the stories of their adventures.

BOB GARFIELD: Books that they turned around rather quickly, both bestsellers. These guys were sort of the Woodward and Bernstein of their day, only probably with better calf muscles.

PETER CARLSON: [LAUGHS] Yes, they were. Richardson’s sold about 90,000 copies, Brown's maybe 70,000. That is a great sale, even today!

BOB GARFIELD: Peter, thank you very much.

PETER CARLSON: Well, thank you.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Peter Carlson is author of Junius and Albert's Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey.

That's it for this week show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, PJ Vogt, Alex Goldman, Sarah Abdurrahman, Chris Neary and Doug Anderson. We had more help from Ravenna Koenig and Alexandra Hall. And the show was edited – by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was Ken Feldman.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our Senior Producer. Jim Schachter is WNYC’s Vice President for News, and our boss. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.

[FUNDING CREDITS] ***END***