BOB GARFIELD: Copyright protections were never supposed to last forever. Copyright was originally designed to carve out a period for creators to profit from their work, after which time that work would enter the public domain. However, copyright extensions in the 1970s and the 1990s, championed by Disney and other entertainment companies, have made it so that copyright protection in the US generally lasts for 70 years after the creator’s death.

Further, these days, any work that someone creates is instantly, automatically copywritten, whether they wish for to be or not, which means that a vast amount of creative work whose authors have died or can't be found has gone out of print and won't be able to be legally republished or even copied for 70 years into the future.

Duke Law School Professor James Boyle runs the Center for the Study of the Public Domain. Since it's the start of the new year, when expiring copyrights transfer creative works to the public domain, we asked him how many masterpieces 2013 so far has seen unlocked.

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: Nothing.

BOB GARFIELD: Nothing.

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: Nothing at all.

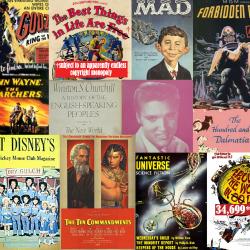

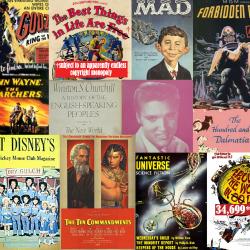

BOB GARFIELD: Maybe I'm mistaken. I was under the impression that Minority Report by Philip K. Dick and Diamonds are Forever, Ian Fleming, were due to expire, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, 101 Dalmations. What happened?

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: All of those works would have been entering the public domain this year. We do a study every year of the material that would have been entering the public domain, if we’d had the laws we had until 1978. Back then, copyright lasted for 28 years, and then after those 28 were up, you could renew and get another 28 years. And so, the stuff that was 56 years old would have come into the public domain.

But, unfortunately, Congress changed the law in the 1990s, and now we will get absolutely nothing entering the public domain this year. In fact, we will have to wait until 2052 for many of these works.

BOB GARFIELD: So the world doesn't get to have free access to The Man Who Knew Too Much. What's to keep me from just saying, “que sera, sera?”

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: Most of our cultural heritage in the great libraries of the world is not commercially available. Much of it’s orphan works, works where we don’t even know who the copyright owner is. The effect of copyright term extensions is to lock that stuff up and make it practically inaccessible. We can’t digitize it, we can’t put it online. We can't have new editions, we can’t make Braille editions for the, for the blind. All of these uses are foreclosed when only a tiny fraction of these works are still actually commercially available and still making money. So we’ve effectively locked up the entire pudding in order to confer benefits on one raisin. And that’s a real cultural tragedy.

BOB GARFIELD: I’ve [LAUGHS] never heard that phrase before.

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: That’s because I just made it up.

BOB GARFIELD: That’s – [LAUGHS]

[PROF. BOYLE LAUGHS]

- unexpected and delightful. Now –

[PROF. BOYLE LAUGHING]

- the fact is that we could have been having this very same conversation a year ago, when a different list of familiar works also did not find a way into the public domain, as they would have prior to the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act. So why are we having this conversation?

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: I see increasing attention being paid to this, I think there’s an entire generation growing up for whom books are the realm of inaccessible culture. When I was a [LAUGHS], a student, books were the realm of accessible culture and informal culture was the stuff you couldn't find. You know, sure, there was someone who had a great recipe for, you know, apple turnovers who lived in Massachusetts, but what’s the chance that I would ever find it?

Now all stuff is up on Facebook, but all of these movies, all these songs, that stuff is all locked up. And even though no one’s making money off it and we don’t even know who the copyright owner is, we’re forbidden from making it available.

I think to a lot of young people nowadays, that just seems silly. And so, nowadays it actually doesn't seem strange to hear people talk about copyright activism and copyright public interest works, when I think back, you know, 20, 30, 40 years ago, the idea of copyright and, and social protest was about as likely as, you know, proctology and social protest. It was simply not two ideas that you’d hear in the same sentence.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, Sonny Bono is dead and the Internet has evolved in a way that the Congress in the 1990s almost certainly could never have imagined. What are the prospects for legislation that would undo the damage, as you see it, that was done with the legislation 20 years back?

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: On the one hand, I could give a pessimistic answer. I could say that the forces pushing on one side are, you know, highly concentrated and that, you know, they want, obviously, their copyrights to continue to be renewed. But I think there is some prospect of a change. I think people would love to have, you know, a Google Books that really included all of these commercially unavailable and orphan works or, for that matter, a national library or a Library of Congress that did. If it happens, first I think it will happen with so-called “orphan works,” works where no one owns the copyright or rather, no one can be identified. There, there’s no positive side to locking things up.

So it’s not that we’re going to get the famous commercial works, but it’s actually that we’ll begin to reclaim the culture of the 20th century and make that available on the Internet, on this amazing new technology. And if I could get that alone, I would be totally happy with it.

BOB GARFIELD: Well James, whatever will be, will be.

PROFESSOR JAMES BOYLE: [LAUGHS] Yeah. Thank you so much.

BOB GARFIELD: James Boyle is the William Neal Reynolds Professor of Law and co-founder for the Center for the Study of the Public Domain at Duke Law School.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]