BROOKE GLADSTONE: As popular as Facebook is, it has its share of detractors, especially among public intellectuals. Former New York Times Editor Bill Keller accused it of, quote, "displacing real rapport and real conversation." Novelist Jonathan Franzen said platforms like Facebook are, quote, "great allies and enablers of narcissism that to friend a person is merely to include that person in our private hall of flattering mirrors."

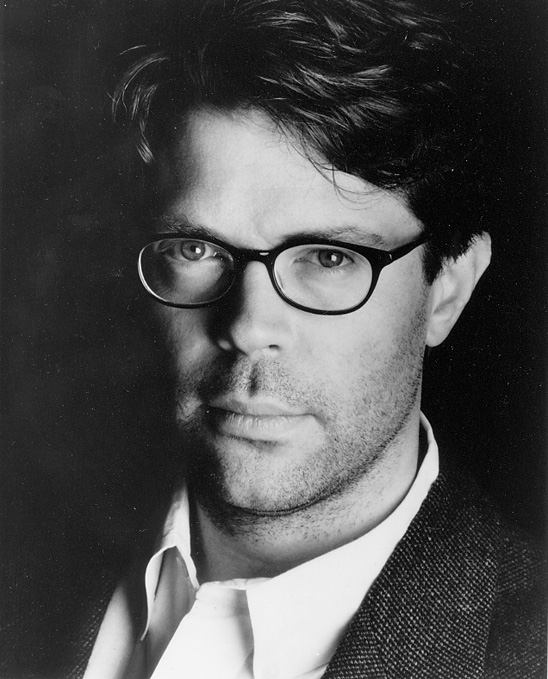

All this angst for a website that lets you share cute photos of your dog with your friends. Where's this agitation coming from? Is it fair? Writer Paul Ford published an essay last year that tries to answer that question. Paul, welcome to On the Media.

PAUL FORD: Thank you for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You wrote the essay about Facebook's fight against something you call the Epiphanator.

PAUL FORD: That's right.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS]

PAUL FORD: So the Epiphanator is the great clanking machine that sits in particular in New York City and especially in Times Square and produces stories. It's the media industry. And what the Epiphanator does is manufacture epiphanies. And the, the point there is that when you read a story in a magazine or, or listen to the radio, there tends to be an ending. By checking in on Facebook or Twitter on a moment-by-moment basis, you start to have this experience of an unfolding sort of never-ending stream of experience. It doesn't have an end. It doesn't conclude.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But don't we even think of our own lives in terms of stories? Isn't that an inevitable framework for no matter how much data we happen to encounter or collect?

PAUL FORD: Well, I think when you look at Facebook you can actually see that they're trying to deal with this but they're trying to deal with it in a way that database nerds would always deal with it, which is the timeline. Look, you made 79 friends in 2010, good for you. But that's not really how it works. If I go down to the bodega and I get a Diet Coke and on the way back somebody gets shot, I don't come to you and go, "Brooke, I got a Diet Coke, and somebody got shot." I tell you, "Oh my God, you won't believe what happened, and I compress that story. And so, that's where it's weird. However, hundreds of millions of people are now starting to get their stories in these streams, and they — they're not so worried about an end or a beginning. What they want is to just have that experience and to swim in it.

What's interesting is that people like Bill Keller, who you mentioned, and Zadie Smith, people like that, really do see that as a terrible loss.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Maybe we need to distinguish between people who use Facebook and people who write for a living, like Zadie Smith, you mentioned, who said that when a human being becomes a set of data on a website like Facebook, he or she is reduced. Our denuded network selves don't look more free; they just look more owned.

PAUL FORD: What she's not seeing is that Facebook in a way is a kind of machine. Like all the data points, the denuded data, they don't function unless the machine is turned on and people are connected to it and they are communicating and sending status messages. And if you go back and look at old pages and old updates and old "likes" it's kinda eh; it's all about that moment.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What do you make of Jonathan Franzen's complaint that it isn't just a waste of time but that it actively obscures a true picture of the world because people are distracted and blinded, as he says, by their own narcissism?

PAUL FORD: There is an obvious immediate truth to that. There's too much signal, it's too hard to figure out what's actually going on. But when I think about some of the interactions I've had on Facebook with friends who have been going through extremely serious, almost sort of Franzen novel level personal distress, people who have been trying to recover from cancer, people who have lost children, and watching them use Facebook to broadcast where they are at that moment so that everyone doesn't call them up and say, how are you doin' today, being a friend of these people I get to watch how they reconstruct their lives. And it's, it's far more painful as a sort of narrative experience than anything I've ever read in a book. And so, I'm very, very cautious to disparage that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: These critics expect us all to use information in the same way, but people who are chronicling the moment of their lives are not engaged in creating stories, filtering information, making one thing more important than another. They are using this information toward a different end.

PAUL FORD: No, that's exactly right. It provides a different experience for them, and, and it still has meaning, it's still valid. Hundreds of millions of people are really happy to have that Facebook experience, and I think an awful lot of them are also still very happy to have the experience of reading the novel. I don't necessarily see that there's this tremendous split between people who would use one and, and the other.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Okay, so Facebook which now tips the scales at a billion users, will be the platform on which we communicate for years to come and critics worry about the fact that Facebook encourages its users to fit themselves into a frame, whether it's what 1950s cocktail you are or what movie star you look like or any number of precut frames, and then maybe we also start thinking of ourselves in those terms and we tailor ourselves according to these sorts of things.

PAUL FORD: I think on the Web we create ourselves by the forms that we fill out, and Facebook has created those forms so that people return over and over and create a social territory that can be very easily shared with many, many advertisers. We construct ourselves in a way that ultimately can be packaged and resold, and so, if the people like Sadie Smith or Jonathan Franzen have a point, it's that we should be very suspicious of the motives of the company that would have us do that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you very much.

PAUL FORD: Thank you very much.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Paul Ford wrote Facebook and the Epiphanator: An End to Endings for NYmag.com.