Lexicon Valley takes on Mad Men

BOB GARFIELD: Mad Men’s fifth season ended this month. One of the reasons people love the show is because it so meticulously recreates the world of Manhattan in the 1960s. A lot of this is actually achieved through sound and language. On Mad Men, old phones ring [PHONE RINGING], like really ring, as opposed to chirp, dress shoes click, typewriters clack.

[MAD MEN CLIP]:

AARON STATON AS KEN COSGROVE: D'Arcy's out.

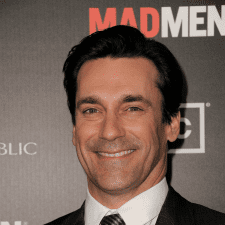

JON HAMM AS DON DRAPER: Says who?

KEN COSGROVE: Arthur's girl told me on the QT. She said he was in his office crying.

[END CLIP]

BOB GARFIELD: And the language is different, or at least it’s supposed to be. While costumes and set decorations are dead on, verbal anachronisms sneak in with surprising frequency. We just don’t notice them because to us most modern speech doesn’t sound modern, it just sounds like how people talk. And it’s not as if Mad Men fans are equipped with some magic algorithm to spot the mistakes.

But Benjamin Schmidt is. He’s a visiting graduate Fellow at Harvard’s Cultural Observatory, and part of the group that worked to develop a searchable database of around 5 million books Google has scanned. He takes every Mad Men script, isolates every single phrase, feeds those phrases into his program and compares them to the period language from his Google Books database.

What you’re about to hear is an excerpt from the podcast I co-host with former OTM Producer Mike Vuolo, called Lexicon Valley. Mikey, take it away.

MIKE VUOLO: Something that Schmidt’s data shows is not just areas in which we’re bad at capturing the language of the past, but some areas in which we’re actually pretty good. It turns out that the language of technology is something that we tend to get right, with one exception [LAUGHS] that proves the rule. That’s language around the use of the phone, possibly because [LAUGHS] the phone seems to us like one of those eternal entities, and so we don’t imagine that the language we use to describe the way we deal with the phone has changed. Here’s Ben Schmidt:

BEN SCHMIDT: Two episodes ago Don Draper said [PHONE RINGS] that they couldn’t leave the representative from Jaguar “on hold.”

[MAD MEN CLIP]:

SECRETARY: Roger Sterling’s office?

ROGER STERLING: I want all the partners here.

DON DRAPER: You can’t leave ‘em on hold.

ROGER STERLING: Where’s Pete?

[END CLIP]

BEN SCHMIDT: It turns out, looking at this huge database of text, that people almost never said, “on hold” back then. There were hold buttons on phones, but the only way that they used the word “hold” was to say, “Could you hold the line, please.” People hadn’t been spending so much time on hold. The hold button wasn’t so ingrained in popular consciousness that there was this idea of this state that somebody could be in, which was being

“on hold.”

[MIKE LAUGHS]

That doesn’t seem to really emerge until the 1970s.

BOB GARFIELD: More, more.

MIKE VUOLO: [LAUGHS] You love this.

BOB GARFIELD: Yeah [LAUGHS], I do.

MIKE VUOLO: There’s an episode of Mad Men in which the office gets a Xerox machine for the first time, and it’s a big deal. And nothing about the way they talk about it jumps out in the data as strikingly anachronistic. So, again, they’re pretty good at getting technology right, but then when somebody gets on the phone again, something does jump out.

BEN SCHMIDT: “I just got off the line with X.” This appears so often in the show, but it appears almost never in the actual printed texts from the era. Sometimes they’re starting to say, “And try to get X on the line, try to get Lee Garner on the line.” But, again, it’s about the state of talking on the phone, where you wouldn’t necessarily think, “I was on the line with him, now I’m off the line with him.”

MIKE VUOLO: So the language around technology, social change, with the exception of the phone, is consistently time appropriate in Mad Men, unlike the language of business, which the show consistently gets wrong and inserts phrases that are far too modern for the time.

BOB GARFIELD: Wow, this is doubly shocking for me, Mike, because I’m well informed on the history of advertising and the agency business in the sixties and, you know, I thought I knew the, the jargon pretty well. I would go so far as to say I would imagine I’m an expert in the subject. And I have seldom winced at any kind of terminology that comes from the character’s mouth. So this is going to be really ugly for me in the next minute, I’m – I’m suspecting. [LAUGHS]

MIKE VUOLO: [LAUGHS] Prepare to wince!

BOB GARFIELD: Uh!

BEN SCHMIDT: So there are all these terms like “deal breaker” which doesn’t appear until the 1970s, using “to leverage” as a verb, using phrases like “level the playing field” or having Don Draper get a “signing bonus” or telling somebody to keep a “low profile” in meetings.

[CLIP]:

DON DRAPER: Did you talk about television?

PAUL KINSEY: I have a meeting on the books.

PETE CAMPBELL: He talked a lot about radio. And Kinsey.

DON DRAPER: You’re gonna have to keep a low profile on this, but it doesn’t mean you’re not working.

[END CLIP]

BEN SCHMIDT: None of those were phrases that were used in any significant rate in the early 1960s. And some of them, that’s actually really sort of culturally significant. “Leverage” is my favorite example on this one because nowadays investment bankers, hedge fund guys, that, sort of the highest glamour point in American business, and the language of high finance trickles down into sort of all of our common vocabularies all the time. But back in the 1960s, finance – banking was not a particularly glamorous sector.

In fact, the most glamorous sector was advertising. But having them using all of this language from the 1970s and the 1980s, when we moved from the sort of consumer capitalism towards more financial capitalism more recently, doesn’t really get the business environment right.

BOB GARFIELD: Ah-ha, finally. He mentions a, a term that I did recognize as having been out of place.

MIKE VUOLO: What’s that?

BOB GARFIELD: And that is “leverage” which is my – continues to be a bête noire for me because I’ve – in the modern era it comes out of the mouth of advertising people about every six and a half seconds. When they mean to say “take advantage of” or “exploit,” they say “leverage” and it just – it makes me cringe.

MIKE VUOLO: So Schmidt, as part of his dissertation, unrelated to Mad Men, does research on the advertising industry in the 1940s and 50s. So he’s a bit of an expert, as well, at this point. And when his algorithm suggested that “focus group,” which is used in Mad Men, was anachronistic, he thought that must be a mistake, because he was sure that he had seen the term “focus group” in these obscure trade magazines that he had hard copies of and were not in his database.

So he went back to the magazines to check and prove his algorithm wrong and, in fact, he found the phrase “focused interview,” “focused group interview” but he couldn’t find anywhere, in these magazines from the forties and fifties “focus group” as its own standalone noun phrase.

BOB GARFIELD: He probably would have had to look at the trade publications beginning in the mid- to late-seventies to locate it.

MIKE VUOLO: Mm-hmm, yeah. And that’s, in fact, when it starts to show up, I think, in the database. And so, it may be that this sloppiness with regard to business language, more so than in other areas, is particular to our time. Or maybe there’s something universal going on here.

Schmidt found an interesting piece of evidence. He put the full text of Edith Wharton’s novel, The Age of Innocence through his algorithm. The Age of Innocence was written around 1920, and is set in the 1870s. In other words, it’s purporting to capture the way things were a half century earlier, just like Mad Men. And the database shows an apparent anachronism in the following sentence:

WOMAN READING FROM THE AGE OF INNOSENCE: Dr. Carver is a very clever man. He wants a rich wife to finance his plans, and Medora is simply a good advertisement as a convert.”

BOB GARFIELD: So Edith Wharton pulled a Matthew Weiner, huh, “One man’s leverage is another woman’s finance.”

MIKE VUOLO: Yeah, exactly. To finance, as a verb, used colloquially in this way, didn’t emerge until later, the 1880s and 1890s I think really, for sure. Edith Wharton in the 1920s wouldn’t have necessarily known that. So why would we be so careful with the language of technology and social change and get that right more often than not, but not business? Schmidt has a theory. Here it is:

BEN SCHMIDT: You have these really strong ingrained narratives of progress and technology. The technology is always advancing. And that helps us remember that technology is always really deeply historical. And we have that same idea for race relations and for gender relations, that we’re on this upward slant and it may be interrupted and it may go from side to side, but that one of the things that’s really defining about 20th century America is that we have had a really progressive forward-moving narrative about social change.

And, for the most part, we don’t have that about business. In fact, we tend to think that a lot of business language is eternal, and a lot of the ways that our culture talks about – business is that they’re sort of eternal acts of capitalism or eternal facts about the ways that corporations work that makes it really hard to realize that, in fact, business organization, business language changed dramatically in the last 50 years. “CFO,” chief financial officer is used at one point in Mad Men but, in fact, businesses didn’t even have CFOs until the early 1970s - that they called CFOs.

MIKE VUOLO: I think it would have been even more jarring if they had referred the “chief privacy officer.”

BEN SCHMIDT: Yes, exactly. At least they don’t have an IT guy.

BOB GARFIELD: You mentioned progress in society, that we do have a pretty good timeline on. I notice that black people in Mad Men are, are referred to as “Negroes,” which is supposed to sound jarring but was very much the terminology of the day. And if they said “African American” or even “Black” in the episodes that take place in 1964, that would make you flinch!

MIKE VUOLO: That would be entirely incongruous. And, of course, they don’t make those mistakes, right? I mean, there’s no fax machine in Mad Men. This timeline that we have for technology and for social change is very deeply ingrained in our consciousness.

BOB GARFIELD: Still, it shocks me that no one was ever told to “keep a low profile” in the meeting. That just seems as timeless as can be.

MIKE VUOLO: Well, maybe they had some other way of expressing that idea. Like with a lot of these things, it’s not that the sentiment didn’t exist. It’s just that the words we use to describe that sentiment were different.

BOB GARFIELD: Okay, fair enough. But Schmidt, in his research, is using all of these countless millions of books, which are, of course, written speech, written speech reflecting spoken language but nonetheless written. Is he sure that they are a fair representation of contemporaneous language for the times in which the various books were written?

MIKE VUOLO: That occurred to me, and it occurred to him. He’s done a few things so far to convince himself that that’s the case. First, he ran some scripts from early 20th century plays and radio shows, to determine whether or not the dialogue in those would map closely to books from that time period. And they did. He did the same thing with movie scripts from the sixties, and he found a similar close mapping to books from that time.

But that’s still written material, for the most part, right? It’s not candid off-the-cuff dialogue, which is really hard to get, right, recordings from the 1960s? Who has those? And it’s even harder to get transcripts of that stuff. But there is one such body of work. Can you guess what that might be?

BOB GARFIELD: Mm, the Congressional Record? Am I warm?

MIKE VUOLO: You’re actually really warm. I mean, the Congressional Record is probably not quite as conversational as he was looking for, but you might remember that Kennedy and Johnson and Nixon recorded many, many hours in the White House, of meetings and conversations with them and their aides. A lot of that stuff has been transcribed. He took all of it and ran it through his algorithm and checked it against the database. And those conversations map very closely to the printed material from that time.

So he feels pretty good that the database is large enough that it does approximate the way people would have used language in that time, with the exception of one category of words that he’s had to, in fact, take out of [LAUGHS] his data set. And those are swear words, right? I mean, people from the early 20th century and people in the 1960s cursed maybe as much as we do now, but they didn’t print it very much.

BOB GARFIELD: So if we want to know whether the profanity in say Downton Abbey is historically accurate –

[MUSIC]

MIKE VUOLO: We’re [expletive] out of luck.

BOB GARFIELD: [LAUGHING] Yeah. I’ll say 1960 for that one.

MIKE VUOLO: I’ll have to check the database.

BOB GARFIELD: For more information about where to listen to the unedited version of this and many other Lexicon Valley episodes, go to onthemedia.org.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

That’s it for this week’s show. On the Media was produced by Jamie York, Alex Goldman, PJ Vogt, Sarah Abdurrahman and Chris Neary, with more help from Eliza Novick-Smith and Amy DiPierro, and our show was edited this week by our Senior Producer Katya Rogers. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineer this week was John DeLore.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Ellen Horne is WNYC’s senior director of National Programs. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is produced by WNYC and distributed by NPR. Brooke Gladstone will be back next week with a special on Mexico. I’m Bob Garfield.