BROOKE GLADSTONE: Even if the prospect of a third-party run is dim, the driving force behind the idea blazes bright, the sense that this election poses a threat to the party system as we know it, that this year could produce what eminent political scientist Walter Dean Burnham famously termed a “critical election,” leading to a political realignment and historic reshuffling. It happened after the 1932 election, when the Democratic Party created a majority base around African-Americans, farmers and Southern whites, and after 1968. When civil rights became a national issue, Southern whites gravitated toward the Republican Party. Burnham calls critical elections surrogates for revolution, when pressure from an unresponsive political establishment accumulates like gas from a faulty valve.

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: Then a triggering event occurs. It can be anything. Back in the 1850s, it was the passage of an act that opened up parts of the free West to slavery, for example.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: And in the 1890s, it turned out to be the battle over silver versus gold in the currency. And in the 1930s, it had a lot to do with, of course, the great smashup when unemployment was 25 percent in some places and where I was, in Pittsburgh, it was 35 percent. That was real misery. And the Republicans had always claimed they know how to manage a modern economy and that argument perished, along with the stock market crash of 1929.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And 1968?

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: The triggering event – there were several-fold happening simultaneously. One of them is the civil rights movement, which already had begun to impose a second reconstruction on the Jim Crow regime in the South. The other was, of course, the Vietnam War –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: - which was intensely unpopular and got more and more so as you approached the end of Johnson's administration. And then the Democrats parachuted in Hubert Humphrey, who’d never entered any primaries, at the last minute to head off the insurgents under Gene McCarthy and, until he was assassinated, Bobby Kennedy. The establishment won out but there was a riotous convention in Chicago.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Burnham says that what we seem to be undergoing now is part of a realignment. The country and its institutions are shifting in segments, a process that began with the transformation of economic policy in the Reagan administration, the first part of what he calls a realignment sequence. Now, after a slow build, come the triggering events, caused by the deepening disconnect between the government and the governed and caused not just by Reaganomics but also bipartisan trade agreements, the outsourcing of factory jobs, and a lot more.

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: What that did was create a bifurcated society. The folks who were plugged into the high tech, who were plugged into adequate education, they’re part of the blessed. The ones who weren’t up on high school or whose fathers and grandfathers used to be able to get nice jobs in manufacturing, [LAUGHS] certainly could actually run what they called a middle-class existence, these guys are part of the cursed.

A triggering event over the longer timeframe was the great crash of 2008-2010. That was the second-worst crash in more than 100 years. While the banks got out scot-free and while, at the same time, those at the very top were making out like bandits, this was a case in which elite malfeasance and nonfeasance played an extraordinarily important role. And that paved the way for, among other things, the abrupt emergence of the Tea Party in 2009, followed by the collapse of the Democrats in 2010 at all levels of election.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Is this realignment going on just within the GOP?

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: No, look at Sanders. He beat Hillary in Indiana, of all places, a socialist from the smallest state in the Union practically, who bangs away at the basic issues of economic malfeasance and nonfeasance affecting very large parts of the population. It’s reflective of a fragmented political system which is in the grips of a basic crisis of identity and a basic crisis of legitimacy.

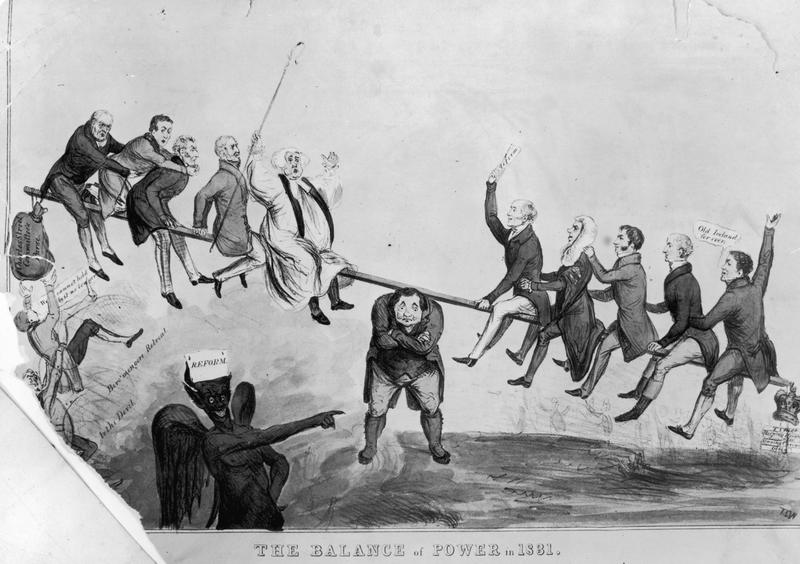

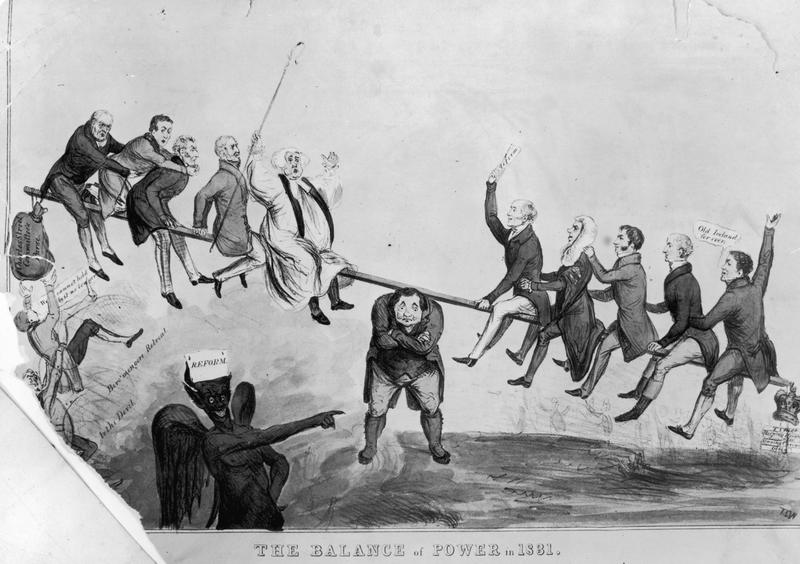

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I leaned on Burnham for a historical analogy to today and, after some pressure, he came up with the election of 1854, spurred, in part, by the opening of vast tracts of the West to slavery. But not only that.

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: It was a case when one of the parties was destroyed absolutely. Another was crippled. A third arose from absolutely nowhere, and it had nothing to do with the Republicans initially. It was the Know-Nothings, the Americans, the ones who really wanted to go and for Irish Catholics and were not interested in slavery, sectionalism or anything else. It’s where we had the largest influx of immigration proportionate to the size of the resident population we ever had. I mean, it’s exactly where a lot of the support for the Tea Party came from in 2009. They are very, very committed to the notion that we need to take our country back again. From whom? I assume blacks, other minorities.

Take a look at the rise of Donald Trump. He is not only a master showman but he’s also a symptom. He entered into something that was a total vacuum. The establishment completely lost control of the situation and never regained it because polarization has reached heights never before seen in modern times. You’ve got to go back to somewhere around the Civil War era to find its parallel in roll call voting.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you very much.

WALTER DEAN BURNHAM: You’re very welcome, and good luck.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Walter Dean Burnham is professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin.

Sean Wilentz is the George Henry Davis 1886 professor of American History at Princeton University, and he says that this is the year when a political cliché comes true. It may actually be the most important election of your lifetime.

SEAN WILENTZ: The point is that we’re at a crossroads, and the country’s either going to become one thing or the other. And this has been building up for 40 years. The Republican Party is in control of most of the statehouses. They have control of the House of Representatives, they have control of the Senate and, until Justice Scalia's demise, it was a very conservative Court. So they were in control of everything, except the White House. If a Republican does win the White House, one party will be in control of American government from stem to stern. If a Democrat wins, there’s a reasonable likelihood that the Senate will fall back into Democratic hands. And, with the Scalia vacancy, then the Supreme Court would look extraordinarily different than it would if a Republican were elected.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How would you situate this moment in the history of partisan politics?

SEAN WILENTZ: Well, at one level, it's sui generis. The history of American politics has never seen a figure like Donald Trump before. But, in other ways, I mean, American elections are never identical, but they sometimes rhyme with each other. Watching the television today, actually, and watching what’s going on inside the Republican Party, it looks like something that happened more than a century ago. And that's when two political parties dissolved, first the Whigs and then the Democrats, in 1854 and then in 1860.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That’s what Walter Dean Burnham said.

SEAN WILENTZ: Oh, well – maybe I am a political scientist. [LAUGHS] You know, the Whig Party split in two over the slavery issue, and they could not hold it together. I mean, with Republicans, including both Bush presidents and the last nominee saying we will not go to the convention, we might be seeing, perhaps over the next year, something that would be truly extraordinary, which would be the dissolution of a major American political party.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You don't really think that's gonna happen, do you?

SEAN WILENTZ: It’s not 1854. It’s only rhyming.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm.

SEAN WILENTZ: And it’s not over slavery in quite the same way. What is the most solid base of the Republican Party today? It's the white male South. The strongest element in the base of the Democratic Party are African-Americans. That sounds a lot like the Civil War [LAUGHS] to me. The Republican Party leadership, ever since Reagan, thought that they could, you know, hold together basically a billionaire class party by appealing to the racial and other social stuff and keep those people riled up and call on them every two years, and certainly every four years, to bring them back into power. That base got fed up. They weakened the party, the party structure. It became a very cynical game.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

SEAN WILENTZ: And there was no party there. It was bound to happen, eventually. And they started going down that road because, in fact, there was nobody who could succeed Ronald Reagan. Ronald Reagan was one of a kind. There was no conservative to replace him.

So you started with George H. W. Bush and you started with Gingrich coming up to challenge him, and then the dialectic began. But, in effect, the old party was badly, badly weakened. There’s no center to the Republican Party, as a result. That is not unlike what happened in 1854.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sean, thank you very much.

SEAN WILENTZ: Brooke, it’s been a delight, as ever.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Sean Wilentz is the George Henry Davis 1886 professor of American History at Princeton University.

[MUSIC: ASHOKAN FAREWELL, THE CIVIL WAR SOUNDTRACK/UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: Coming up, is Puerto Rico now paying the price of its bad behavior, or the price of ours?

MALE NARRATOR: As an example of an underdeveloped land that is going through an industrial revolution without violence and without Communism, Puerto Rico has been called a showcase of America.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: This is On the Media.