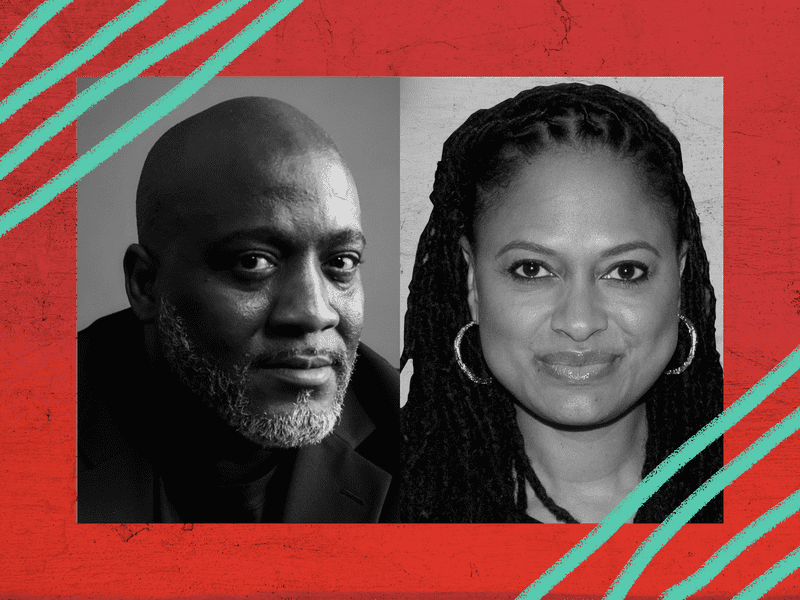

12. Ava DuVernay Takes Us Online, Desmond Meade Leads Us to Vote

Before we get started, I wanted to just give you the heads-up that in this episode, we talk about suicide.

I’m Rebecca Carroll and this is Come Through: 15 essential conversations about race in a pivotal year for America.

A couple weeks ago, I wrote a piece for The Atlantic — and in it, I expressed my strong belief that there needs to be a moral intervention in the minds of white America. Black lives can’t matter until we are seen as human beings first. It was gutting to write in the moment. It was also widely quoted. But now, as demonstrations surge in protest of police violence against Black people all across the country… I’m stunned that it even had to be said.

Especially during these months of quarantine when, from within the confines of our small Brooklyn apartment, I’ve watched my teenage son grow more deeply into his own humanity every day. Not since he was a baby have I been able to witness his day-to-day growth in such an intimate way — the changes in his face, the broadening of his shoulders and tenor of his voice.

I am quietly astonished as I watch him hone his dunking skills on the seven-foot outdoor hoop we bought after lockdown. And a little concerned it will not have served him when he gets back to a full-size court.

He occasionally overhears something from one of my Zoom meetings (yes, our apartment is THAT small), and I can see him building ideas in his brain as he asks me about something I’ve said to a colleague, or raises his own questions about race and racism.

I try to answer him as honestly as possible, but I worry that my answers still won’t adequately prepare him for the country he returns to when the quarantine lifts.

My son turns 15 next month — the same age as Antron McCray and Yusef Salaam when, in the spring of 1989, they and three other teenage boys were wrongfully convicted of rape, and sentenced to 6 and 13 years in prison.

They were known as the Central Park Five, and their story was captured with magnificent humanity by director Ava DuVernay in the Netflix series When They See Us.

This past May, Ava and her multi-platform media company, ARRAY, launched a new online education initiative called ARRAY 101, which uses When They See Us to help high school-aged students understand the threat of systemic racism and to demonstrate the impact of social justice.

I asked Ava to come through for a conversation about her company’s initiative. And I started off by asking about her audience.

Rebecca: So in a recent interview with Gayle King you said, and I’m paraphrasing, that the thing that many creatives in Hollywood fail to do is to make the connection between the thing that you’re making and the people who are watching. In particular, young folks. And it occurred to me, you know, the switch to online learning due to Covid and quarantine made it pretty clear pretty quickly who suffers from that arrangement. And it’s Black and Brown kids who don't have access to wifi or computers. So I wondered how, if you were concerned about that for the audience you hope will have access to your initiative.

Ava: Yeah, I'm concerned about everything, you know. Every solution is not going to solve every problem, but to not do it because of the digital divide would be to leave out a bunch of kids, Black and Brown included who can download it. You know, most kids have a phone. Uh, we know that we're dealing with, you know, some numbers that have nothing, no digital connection. But we know that, you know, the majority of kids and, um, from finding 86% of teenagers have a cell phone of some kind. And so we got up better to try to serve them, um, rather than not do it at all because of not being 100% perfect. So certainly it's a concern and certainly we need to try to figure out how to reach those kids. In the meantime, as a filmmaker who does not work in education, I felt like my responsibility was to try to go a step further and to do the best I could. You know, since we've announced this, we've gotten hundreds of messages, social posts, DMs, texts, emails, to ARRAY from, you know, grownups who just wanted to go deeper when they watched When They See Us. And so we made the piece with an eye toward serving independent study at various age levels.

Rebecca: I also feel like what you're making, you just referenced it as entertainment. But to me particularly, When They See Us, it's more than entertainment. It's more than TV and film and images of us. How do you describe the thing that you are making?

Ava: Um, I'd describe it as storytelling. I'm a storyteller, whether I'm using the medium of film, television. Whether I'm, you know, moving information around to these learning companions. You know, whatever I'm doing, it's some form of storytelling. Uh, but so much television is entertainment. There are actors, there are lights, there are scripts. And, you know, you have to keep people watching, you have to make sure that you have proper act breaks and, you know, proper beginning, middle, and end to scenes. And so there's a whole, uh, language of film and television that, you know, for me, all those follow the category of entertainment, which is separate from when I'm making a speech or when I'm writing a paper or whether I'm interrogating things in the real world and the different ways that I do, the art practice is one that takes on the tropes of entertainment. I think that's okay. No bad word, but yeah, you know, that's what it is. The overall umbrella is storytelling, though.

Rebecca: And you're launching this initiative with When They See Us, I've watched it three times. It haunts me.

Ava: Oh wow.

Rebecca: I kept going back to it. I felt kindred to it. My son, my teenage son, has only watched parts of it. I'm letting him work through it at his own pace. What would you want him to take away from this work?

Ava: I would want him, at his age and, you know, who he is and what he looks like in the world as he walks out the door, to watch it as a defensive precaution. He needs to know what his rights are and he needs to know what can happen to him. He needs to know how people view him. He needs to watch it in a way that is protective so that he can, you know, kind of be armed with knowledge. It’s just vitally important. You know, we watch these pieces that are framed as entertainment, they use the tropes of entertainment, but ultimately inside we're telling stories of each other. We're passing down, you know, vital information from generation to generation about how to protect yourself, how to come home at night. So I would hope that he gets to the end of it and it's not a sad story about people outside of him. That it's a story he can carry with him, you know, to protect himself as he walks through the world.

Rebecca: And is there specific curriculum in the online learning initiative that builds on that?

Ava: Well, all of it is designed to elevate and kind of extend one's viewing. You know, one of my favorite lessons is a lesson that has to do with data statistics. You know, I wanted to put a math lesson in this and, uh, the groups that we worked with to put it together really took that challenge. And there's a whole database study where, you know, young people or anyone can go into the NYPD crime database and start to do data analysis and answer math questions and just kind of understand how to read data. Um, you know, whether it's, you know, understanding how many Latinx men are arrested in the Bronx on days where the temperature was over 80 degrees. Um, as opposed to, you know, Caucasian men who were arrested in Manhattan on days when it's over 80 degrees and people are outside. And so anyway, that kind of analysis and applying mathematical analysis to it, um, just show that, that, you know, these stories have to be attacked from all avenues that our base of knowledge can stand in all kinds of ways that we can never stop learning. And so our goal is to use our stories as a step to continue that.

Rebecca: And so speaking of, of police and over-policing and over-indexing with black and Brown bodies, you know, the current sociopolitical climate is obviously deeply, deeply unsettling. I would say for Black folks, especially, but I've also grown kind of tired of hearing white people say, “I’m so sorry, what a terrible time to be Black in America.” Because I actually love being Black all the time. And the terrible state of things is more on white America and its moral bankruptcy. And so what do you think this, this online initiative, the work that you do, can educate and celebrate each other as Black folks while also making clear that we're not the thing that's terrible to be in America.

Ava: Oh, I mean, no one's ever said that to me. So, that'd be interesting if someone said, “So sorry you’re Black,” to my face. I would, that could actually be an interesting conversation.

Rebecca: What would you say?

Ava: My mouth would be dropped open as it is now. I can't even imagine… I mean, it's not something that's in my mind, what white people think of the work or what they think is terrible, um, as I'm doing anything. So it's hard for me to wrap my mind around that question, because it's not a question. They're saying, “It’s a horrible time to be Black,” is based on their, you know, perception of Blackness or perception of the times and their lack of understanding that this is a continuum, um, that this isn't a time that's actually much different than any other time we've been in. Um, but that, you know, within, within, uh, Blackness is a deep joy that they can never understand.

Rebecca: And just lastly, how do you think this initiative would have resonated with young Ava?

Ava: I would love it. I would love it. That’s a good question. I would, I would have loved to have this as a young person. I was, you know, very, uh, wanting to learn more about how to participate in the world and be an active citizen and believed in justice and dignity for all then as I do now. I remember being,when my aunt, Denise, introduced me to Amnesty International at a U2 concert and I got a little pamphlet and, um, I remember reading that pamphlet and, you know, learning more and buying books. And it was just that little piece of something that said, “You know what? There's more than you in the world. Look outside, look beyond. Think about the plight of other people. Think about the majesty of other people outside, where you sit.” Um, all of that opened up a whole new world for me. So I actually thank you, Rebecca, for making that connection for me. I never thought of this possibly being that. Um, but if it could be that for any young person, um, it would be a success. Uh, so here's hoping.

Rebecca: Well, I'm very eager to share it with my own child, especially during this time. Um, and I thank you for the work that you do as ever. Um, so appreciate and admire you.

Ava: Thank you. Thank you for having me on.

Ava’s series, When They See Us, is a powerful story to help further a national dialogue around social justice. But in order to pass the policies and change that social justice demands, we have to vote the right people into office. This applies, of course, on local and state levels, but as we head into what may be the most important presidential election of our lifetimes, how do we restore our faith in the value of the vote? Or in democracy for that matter?

I figure that if anyone can lead us at least in that general direction, it’s Desmond Meade. Because Desmond’s personal journey is inspiring, and he has a real vision for not just his future, but for all of America. And it makes me want to believe in our country more than I have in a long time.

Desmond is the President and Executive Director of the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition — a grassroots organization run by formerly incarcerated people or returning citizens, that works to prevent discrimination against people with convictions – and specifically, to help them re-register to vote. Last year, he led the charge on Amendment 4 in Florida, the biggest voting rights win in half a century.

But at a time when people are either stuck in their homes or protesting in the streets, the idea of an election just feels very far away. And also, like, how is that gonna work? Even though, clearly, voting now is more important than ever.

Desmond has an extraordinary life story — one that he draws strength from every day, and that informed his vision for a future he didn’t always think he would have.

Desmond: When I was standing in front of all the railroad tracks waiting on that train, uh, I was a homeless. I was recently released from prison. I was addicted to crack cocaine. I didn't have a job. The only thing I owned were the clothes on my back. Right? And I didn't see any light at the end of the tunnel. You know, none of that. And I was, like, ready to end my life, just because there was no use of me living anymore. And that's what I thought at the time. And so I was completely broken.

Rebecca: So, when you say “broken,” what do you mean exactly?

Desmond: The night before I actually went to this church just to ask a pastor to pray for me, because I was really just that desperate. And I’ll never forget when the pastor put her arm around my shoulder and pointed at another guy at a different part of the church and told me to go to him and make an appointment for the next day. Now, all I asked was for prayer. So in my head I'm like, “Woman, don't you understand how desperate I am? How do you know, if I'm coming to you and I'm not asking you for money, I'm not asking you for food, I'm not asking you for clothes… I'm just asking you to take a few seconds and intercede for me, on my behalf, to God. Just pray for me.” And she looked at me and told me I had to make an appointment for the next day. I didn't know if I was going to live to see the next day. And I remember walking out of that church thinking, “Man, even God has rejected me.”

Rebecca: That’s a super heavy feeling to leave a church with. How have you reconciled since with that moment?

Desmond: Well, you know, I, I think that, on the surface without having to go too deep, because if we have to go too deep, then this might be one of them counseling sessions. And I don't know if we can do that over the air. But I think that what sits at the heart of it was the fact that, um, I may have had underlying issues that were exasperated by me turning to drugs, me turning to alcohol and where I became so addicted to it, that at the end of the day, everything that I did at one point in my life was geared towards how do I get high or even higher. And so every time that I've been basically in trouble in my life, it was totally around me wanting to be under the influence of drugs.

Rebecca: And how do you remember that person? Are you, are you able to look at that, that person with compassion?

Desmond: Oh yeah. In recovery one of the things that they always say is, “You gotta hate the disease, not the person.” I'm telling you, when you go into those recovery rooms, you see people from all walks of life for real. Right? That, that alcoholism and drug addiction don't discriminate, right? You get democrats, republicans, independents, white, Black, Latinx, rich, poor, middle class. Alcohol and drug addiction does not discriminate. Alright, and in those rooms, you will find all of those people that actually function together because they have a common disease. Right? And they have a common goal and that is to stay clean one day at a time.

Rebecca: And so before you got clean, when you think back about what a day in the life for you was, what did it look like? Can you describe a day for you, before you got clean?

Desmond: A day for me before I got clean… Living in the streets, sleeping behind dumpsters, trying to hustle, beg, borrow, steal any kind of money I can get my hands on so I could buy the drug of my choice and just repeat the cycle over and over again.

Rebecca: Do you remember the first time that you felt, like, a real sense of joy that came from something other than drugs?

Desmond: Oh yeah, I remember it distinctly, you know, it was a time when I was actually still in treatment. I had asked myself if that train would have killed me, how many people would come to my funeral and the answer was zero. Right? And that made me question, what have I been doing with my life and really question about the insignificance of my life. And I'm like, man, if your life that insignificant that nobody would care if you died? You know? And so I took that with me in the drug treatment. And eventually when I came to that realization that I could do something to at least have someone appreciate the time that I've spent on this planet, that was a way for me to go. And it was something that I shared that caused someone to experience a paradigm shift. And so when that happened, when I had that encounter with a young man that actually gained hope based on something that I said, I felt an eruption inside of me that I'd never felt before. I could tell you that it was a joy that I never knew existed. It was a joy that I was chasing all my life and didn't even know I was chasing it. And that was really discovering my purpose, of discovering God's purpose for my life. And it was a very simple purpose. It was just to give back.

Rebecca: So I want to talk about the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, the organization that you lead. Tell me what it is.

Desmond: Well, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition is an organization that's led by people with felony convictions and family members who have a loved one that's been impacted by the criminal justice system. And our claim to fame right now, the fact that we led the Amendment 4 effort, which successfully re-enfranchised, uh, 1.4 million Floridians. And then we have people who have been involved in the justice system have really stepped out in front of, leading in advocacy efforts around reforming this justice system of violence and making it more sensible, humane. And, um, conducive to productivity. And what I mean by that is that a person does something wrong, they get caught, they get punished. After they're punished, they ought to be given every opportunity to successfully reintegrate back into our community and be a contributing member of society. And we seek to remove those obstacles and discrimination against people with felony convictions.

Rebecca: In this really sort of overwhelming moment, particularly for Black folks, it's really difficult to think about democracy and voting amid Covid and nationwide protests. And so how are you feeling right now about the fate of the election?

Desmond: Early on when we were just entering into Covid crisis. You know, I wondered about that and I was concerned because there was so much concern that was being paid to Covid-19. Places where shutting down, movements were restricted. And I wondered about the negative impact that it was going to have in our elections and people not even thinking about elections anymore. They’re thinking about surviving, you know, you have the unemployment crisis here in Florida, and just people trying to figure out how to get by day by day. And so, you know, initially I was concerned, but you know, at the end of the day, I think that all of those things really spoke to the importance of voting and how voting can really be the difference between life or death. And that this was an opportunity for us to really connect the dots where it wouldn't be that difficult to do because of what people were experiencing in real time.

Rebecca: And so how do you make that connection in a clear way to folks who are literally trying to get by day to day, right? There's a reason that it's difficult to convince folks to vote, especially Black folks, because the, you know, and right now the democracy and this country is, for lack of a better term, rigged.

Desmond: Well, I mean, so that's those two things right there. First of all, uh, when you talk about getting, uh, Black people out to vote, we know historically candidates have not even spoken to the issues that Black people were really concerned about.

Rebecca: Right.

Desmond: And so you can't get them out if you can't talk to an issue that they can directly connect to. Now, in this case, there is an issue that people can directly connect to because Black folks are dying at a higher rate than anyone else as it relates to Covid-19. There are Black folks that are experiencing a hardship, economic hardships because of Covid-19. Uh, there are black communities that are being largely ignored as it relates to, uh, Covid-19 testing, you know, and getting provided proper PPE equipment. And so there are just so many things that's going on. And then when you add in the killing of Ahmaud Arbery and…

Rebecca: Breonna Taylor and George Floyd…

Desmond: …That those are things that Black folks are intimately connected to. They experience racism and white privilege on a daily basis. And so this moment that we're facing, actually speaking to issues that politicians have avoided in the past, and which contributed to the lack of participation in the Black community. Right? And so I think that we have a prime opportunity to connect the dots and in turn the African-American community out, like never before.

Rebecca: Okay. So let’s just really bring this home. Say, for example, I don't want to vote. Tell me why I should.

Desmond: You know that, you know, first of all, some people who say that they don't want to vote, a statement that probably proceeds that is that, “My vote don't count.” Right? And what I tell folks is that if your vote didn't count, there wouldn't be so many people trying so hard to actually prevent you from voting. Number two, I will tell you that no matter what your status is in life, when you go into that voting booth, you have just as much power as the richest person in the United States or the most powerful person in the United States, ‘cause your vote counts just as much as them.

That’s Desmond Meade. Coming up - why he still has hope for the justice system. That’s in just a minute.

Rebecca: So I would be really interested to hear what your idea of paying dues means. I really struggle with how it works, right? How the prison system even works. Who gets arrested? Who gets sent to prison? And under what circumstances?

Desmond: Well, here's the deal. So I want to reverse that a little bit, because I think there's been so much discussion along those lines and not what I believe are more important lines. And so what I believe is this, what we know is that at least 95% of people who are incarcerated will return back into our communities. And so the most important question is, what kind of conditions would we want to exist in that community for those people that are coming out? Do we want conditions that will make it difficult for them to get a job, make it difficult for their housing, employment? Do we want to ostracize them in such a way that we increase the likelihood of them committing another criminal act? Or do we want to create conditions in which when these individuals are released, they're given every opportunity to successfully reintegrate back into our community, be a part of our society and help contribute to the successes of our society? And we have to make that decision. What do we want for these folks when they're released? Once we can wrap our head around that, then we can start talking about how we want them to be treated while they're incarcerated. And then we can start talking about whether or not they should even be incarcerated in the first place. But I think we first start with the end game.

Rebecca: So how close do you think we are to knowing what we want, around that conversation?

Desmond: What, you know, I think that we are close. But I think the biggest impediment is partisan politics that drives false narratives in order to strengthen their side of the fence. But I think that we're there, because here's the deal, and I know that we're there. The success of Amendment 4 was the fact that we were able to connect with people along the lines of humanity. And we was able to bring into the fold people from all walks of life, all political persuasions, and that force was driven by love. Right? When over 5.1 million people, which was a million more people that voted for us than any other candidate on the ballot. When those 5.1 million people casted their ballot for Amendment 4, it was not a vote out of hate. It wasn't a vote that was based out of fear, but it was rather a vote that was based out of love, forgiveness and redemption. And that night, uh, in November 2018, we showed the world love can in fact win the day. Right? And one of the references that I used in our campaign, I think it was so descriptive of my campaign, was getting people to imagine how we reacted after natural disasters. We, as a people, when you see a hurricane or tornado ripped through a community… What was that? How did that aftermath look? And what I always seen was people came together to help people. They didn't care about your race. They didn't care about your sexual identity. They didn’t care about your immigration status. They didn't think, they didn't care about your political preference. What they see was another human being in need, and they rallied around that. And it's in those moments that our country is great. It's in those moments that humanity is beautiful. And those are moments that allow us to react naturally without the influence of partisan or rhetoric without the influence of, uh, of these, uh, divisive narratives that drive us apart.

Rebecca: Would you call yourself an optimist?

Desmond: Most definitely. Yeah.

Rebecca: I mean, because you could just as easily talk about what happens in a crisis to Black and Brown folks given the government response we saw with Katrina, with…

Desmond: Woah, look at what you just said, “Given the government’s response…” It's when the government, it’s when politicians get involved, that you have the biggest problems. When you see with the Covid-19 response, Rebecca, the beautiful parts about the Covid-19 response was when everyday people just came together to help their neighbor. The bad things happened when you see politicians get involved.

Rebecca: It's really, it's so compelling to think about it that way. And I think, and I really appreciate the reminder of that. And so, going back to the impending election coming up in the fall, do you think, do you think we're going to get a fair election?

Desmond: You asking me to be a fortune teller now.

Rebecca: Yes, I am. It sounds like you can handle it.

Desmond: You know what? When was the last time we had a fair election?

Rebecca: Okay, word.

Desmond: You know, when you think about it, you know, in the broader sense, you know, what I do think is that people are going to come out. I do believe that. Um, and I'm hoping, you know, that we're doing our part to encourage people to vote by mail, but there are going to be some people, some populations that is going to, uh, just insist on going to the polls and personally casting their ballot. And I mean, I can't argue against that. You know, I could encourage them to mail out their ballots, but they're going to come out. But the bottom line is, is that I do believe that there is going to be a heightened, uh, energy level during this election because of all of the events that's been happening, uh, in 2020. I mean, this has been like a Twilight, uh, a Twilight episode, right? There's just so many strange and outrageous things that's been going on. Um, but thankfully they all lined up with the importance of voting and the importance of distinguishing between a politician and a public servant.

Rebecca: And so just sort of in closing, um, this podcast is about essential conversations in a pivotal year for America, and we called it that before it became, as you said, such a Twilight Zone episode. Um, and so we're asking folks about the ways in which race and racism impact and play out in, um, in their lives and, and in everything that we do as a country. Can you tell me, what is the essential conversation for you about race and racism in your life and work?

Desmond: Oof. What is that conversation? I mean, I remember when I was a little kid and I had this friend, uh, that was white and we thought we were brothers and sisters. I mean, we just did everything together. Uh, and we really didn't, like, pay too much attention to the color of our skin. Um, and I remember after we were, um, her parents moved away and my mom used to love to tell a story about how we were both at the airport. Right? So everybody was saying goodbye to each other. And this young lady, and I was like, we're little kids, like maybe three or four years old. And we were clinging to each other for dear life. Right? And her parents and my parents were pulling us apart. And then when they finally managed to pull us apart and go their ways, we would break away from my parents and run back to each other, clinging to each other for dear life and screaming at the top of our lungs. Right? Those are our precious moments, right? And I have not yet lost hope that we can get to those moments. And I know that they exist and I know that it's, it's possible. Because it shows up in our kids every day. And so I, you know, matter of fact, I think that the theme of this journey is how do we get back to Eden, right? How do we get back to Eden? And I think that those conversations mean that we must deconstruct a lot of these narratives that were implemented or rolled out for the sole purpose of keeping us as a people divided so that a select few will remain in control of our society.

That’s Desmond Meade. He's @desmondmeade on Twitter.

If you are experiencing suicidal feelings or know someone who is, please get help. You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. It’s open 24 hours a day.

Christina Djossa and Joanna Solotaroff produce the show, with editing by Anna Holmes, Jenny Lawton, and Tracie Hunte. Our technical director is Joe Plourde, and the show was mixed by Isaac Jones, who also wrote the music. Special thanks to Jennifer Sanchez and Tracie Hunte.

I’m Rebecca Carroll - you can follow me on Twitter @Rebel19 for all things Come Through - and - if you liked the show, please rate and review us. Thanks so much.