[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: This is The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry. 10 years ago, in 2012, a gunman tied to white supremacist organizations killed six people at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin. It was an act of mass violence which robbed the community that had suffered increasing numbers of hate crimes for more than a decade at that point. Valarie Kaur, a Sikh American woman, author of See No Stranger, and leader of The Revolutionary Love Project has been seeking to document, understand, and respond to this anti-Sikh violence since it began to increase as a result of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hate in the weeks and months following September 11th, 2001.

On Saturday, when a white supremacist killed 10 Black people in a Buffalo grocery store, Valerie tweeted, "I find out about Buffalo while working on a memorial video on the white supremacist mass shooting in Oak Creek 10 years ago. Valerie joined me to talk about the social and political moments when hate violence emerges.

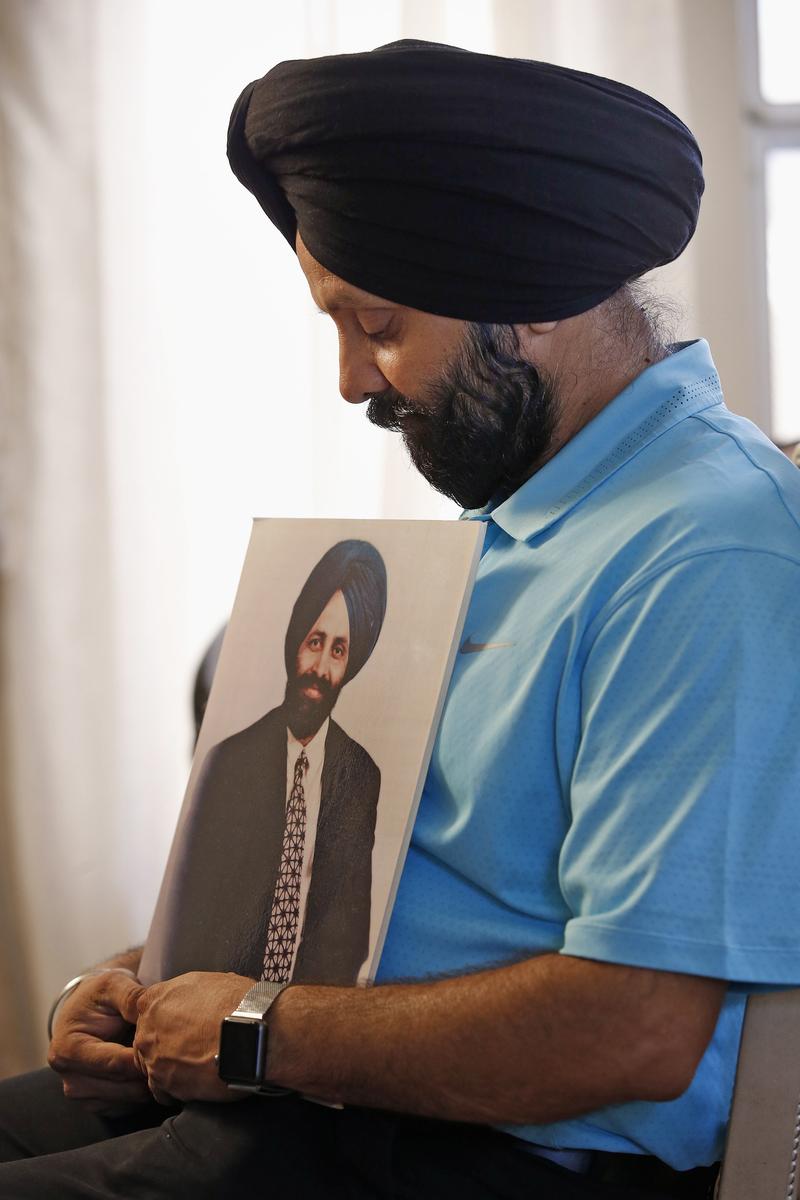

Valarie Kaur: Within hours of the towers falling, we got news of people of color on city streets across America, beaten, chased, stabbed, and then a few days later, the phone call came that Balbir Singh Sodhi had been killed. He was a sick American father, standing in front of his store in Arizona who was killed by a man who called himself a patriot. I called Balbir Singh Sodhi an uncle, and so it was as if an uncle had been murdered. Back then, this was before social media, before we had any channels to tell our own story. It was like our voices, our cries were being drowned out by this anthem of national unity.

In the weeks and the months that followed 9/11, advocates began to use this language that 9/11 caused the racial violence, but I was hearing stories about the violence taking place before Bin Laden's image was ever shown on the screen. The very first person targeted in hate was a young man who was running from the towers falling [unintelligible 00:02:18] when he was stopped by a group of men who said, "Hey, you effing terrorist, take off that turban."

He began to run for his life the second time in the same morning 9/11 simply unmasked the kind of racial stereotypes that had been targeting those of us who are people of color, Sikh, Muslim Americans, as foreigners as enemies to this country. My grandfather experienced those race riots 100 years ago when he first arrived. it simply unmasked what was already there. We had already had to be seen as one of them to be excluded so efficiently from us.

What was different about post 9/11 America is to see the government, the state, in enacting a war on terror, first in Afghanistan, and then in Iraq begin to issue a series of state violence from the war abroad to legislation here on the soil that enacted profiling, incarceration, detention, even designated Guantanamo was a place where the constitution did not reach. We were even designated outside of the realm of the circle of human beings who had human rights.

Every time there was a critical moment in the war on terror, or every time there was an election, we saw hate violence against Sikh Americans, who are not even Muslim, go up. For years, advocates like me, we said, "Okay, we're going to be breathless, we're going to work nonstop because this is the backlash." The backlash kept going, year after year. The crisis response never ended. Until 10 years into it, I realized that 9/11 cast a shadow so long that it was simply the nation that we came to be living in, it simply became the new normal. Now, 20 years later, our communities are five times more likely to be targets of hate than we were before 9/11.

It was at the mass shooting in Oak Creek, Wisconsin in 2012, the largest act of massacre on the Sikh American community since we arrived here. I looked at my fellow advocates, I remember looking into the open caskets of people who looked like my family and feeling like we had failed. What was all that work if not to prevent this? I felt like I was falling into the abyss when a brother caught me and he said, "We may not live to see the fruits of our labor, but we have to keep laboring, and that it's not enough to be known."

This is where so many Sikhs said hopefully if they just knew who we were, then they would stop killing us, but black people are known, indigenous people are known. They don't need to just know us, they need to love us, and at that moment what saved me was the doors of the gymnasium thrown open, and thousands of people filed into that memorial. White people, Black people, Asian people, people of all faiths and races came to grieve with us. 3,000 people came to grieve with us. They didn't even know us.

That's when I realized that you don't need to know people in order to grieve with them. You grieve with them in order to know them. Three days before the Buffalo shooting, I received a notification from a prison in Arizona, that Frank Roque had died. Frank Roque is the white supremacist who took the life of Balbir Singh Sodhi after 9/11, 20 years ago. In hearing about his death, I felt both relief that the story was over and also sorrow.

I also grieved him because 15 years after Frank took Balbir Uncle's life, the family and I reached out to him to talk to him, and he apologized to us. He said, "I'm sorry for what I did to your uncle, and when I go to heaven to be judged by God, I will ask to see your uncle and I will hug him and I will ask for his forgiveness." That is when I realize that forgiveness is not forgetting. Forgiveness is freedom from hate. I could stop hating him because forgiveness was for me not for him. It was for me.

For me, forgiveness came at the very end of a very long healing journey. For others, like the families who saw their loved ones killed by Dylann Roof in Charleston forgiveness came with the very beginning. They looked into the eyes of this young Sikh boy and said, "I forgive you," and I cringed, but I realized that they were saying, "You cannot make me hate you."

For some of us, forgiveness comes at the end, for others at the beginning, for others in the messy middle, for others still you withhold your forgiveness because it's your only act of agency and that's okay, that's up to the survivor. Once we did forgive Frank, it opened up the previously unimaginable possibility of reconciliation. We reconciled with Frank. When he died, instead of it just being a forgotten criminal, we actually wept for him.

Rana Sodhi the brother of Balbir Singh Sodhi said, "He's up there right now, he's asking permission to give my brother a hug," and that made me cry all over again. To see the growth that was possible for this man who I'd seen as a monster. Then for three days later, to see a young kid espouse the same ideologies on this rampage of evil, of this bloodshed, just made me so profoundly sad. It made me feel that every time someone says, "Oh, we just have to wait for those people to die out."

It's like, "Oh, you don't understand how insidious this is, how deep it goes, how far it spreads, how it's woven into our culture, and to have the audacity to say that there are no such thing as monsters in this world, but only human beings who are wounded, who act out of their grief or insecurity or fear that. That doesn't make them any less dangerous, but when we see their wound, they lose their power over us.

I am not afraid of that gunman or people like them, I am sorry for them because I see how inflicted they are. That gives us the power to say who in our own communities can we tend to. It may not be my role as a person of color to attend to that grief, but it may be yours." That's where we have the idea that every single person has a role to play and birthing that nation that is safe for all of us.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Valerie, thank you for giving us that story. Valarie Kaur is a lawyer, a civil rights activist, an author, and the founder of The Revolutionary Love Project. Valarie, thank you for joining me on The Takeaway.

Valarie Kaur: Oh, my love anytime.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.